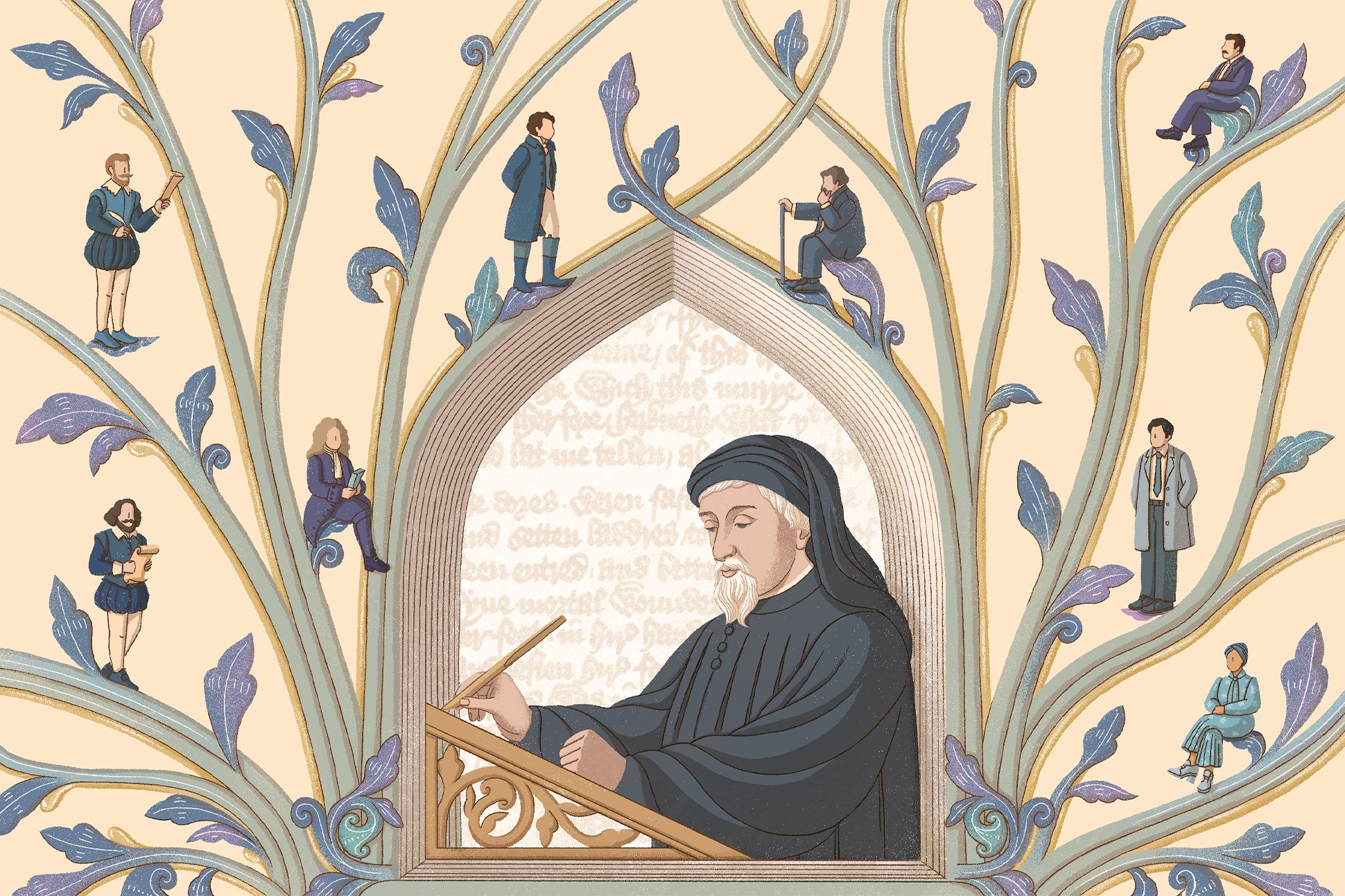

Art: Christina Chung.

A Chaucer fantasy.

What soothes you? Things like a massage, granola, walking, or reading generally work for me. Today, I’m delighting in a literary essay. I’m glad Camille Ralphs wrote at the Poetry Foundation about “how Chaucer remade language.” Good-bye for now to November 2024.

Ralphs says, “Chaucer’s works are very much of their moment, and perhaps required some distance from their context and coevals for their worth to be apparent. Ezra Pound observed that ‘Chaucer had a deeper knowledge of life than Shakespeare.’ If Chaucer hadn’t played so many roles in the medieval city, he likely couldn’t have written so expansively.

“He was the son of a vintner and grew up in London’s Vintry Ward, where he was formed and informed from the start by a babel of trades and trade-offs. He became a page in the house of the Countess of Ulster, a squire in the King’s household, a soldier, a controller of customs in the port of London, a justice of the peace, and Clerk of the King’s works. The Canterbury Tales owes some debt to the genre of ‘estates satire,’ which tallies different social classes and professions and elucidates both their importance to the state and their deficiencies. … Yet there is more reality to Chaucer’s characters than that.

“Who else could have imagined such a motley ensemble but someone who had jostled with the many flavors of humanity? The medleyed voices of the Miller, who can break down doors by running at them with his head; the ‘gat-toothed,’ half-deaf Wife of Bath, who rides astride in bright red stockings; the Canon alchemist, so sweaty from the ride that his horse is a lather of suds; the ‘ful vicious’ Pardoner with his jar of dubious holy ‘pigges bones’; and the garlic-loving Summoner, with a face so pimply ‘children were aferd’ — Chaucer knew them all.

“As Mary Flannery argues in her authoritative and diverting monograph Geoffrey Chaucer: Unveiling the Merry Bard (Reaktion Books, 2024), the mercenary assets of ‘The Shipman’s Tale,’ in which a merchant’s wife offloads a difficult financial situation by insisting she’ll repay her husband with sex (‘By God, I wol nat paye yow but abedde!’) must come from Chaucer’s roving through ‘warehouses, docks and markets.’ Works such as The Book of the Duchess (1368) — probably penned on the death of Blanche of Lancaster, the wife of John of Gaunt (it also circulated under the title ‘The Deth of Blaunche’) — could only be written by a man who’d worked in ‘palaces and great houses in England and on the Continent.’

“For a writer to be all things to all men, he must know a bit about things, and a lot about men — not to mention a lot about language and literature. Had Chaucer not been born into a mercantile environment and had the opportunity to mingle with Italians by the Thames, he may have struggled with Italian, and had he not spent so much time around nobility, he may not have learned French.

“His narratives are mostly borrowed from Latin and Romance-language sources (including Boccaccio’s Decameron, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and the Roman de la Rose by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun). His forms and genres almost all derive from French minstrel romances and fabliaux (bawdy medieval stories), and, more granularly, from the verse structures of poets such as Guillaume de Machaut, from whom Chaucer stole the seven-line form now known as ‘rime royal‘ or the ‘Chaucerian stanza.’ And he may never have thought about writing in English had he not observed how Dante elevated Florence’s vernacular in his Commedia (1321), a technique Chaucer noticed while in Tuscany for diplomatic work. …

“Chaucer never claims to be inspirited by God or gods, nor does he ever refer to himself as a ‘poet’ or ‘author.’ This may result from his ‘distinctive self-deprecation,’ in Flannery’s terms, though comic exaggerations of the scribbler’s incompetence are found in Machaut too, as the scholar Colin Wilcockson notes.

“Such modesty was a way of keeping or getting out of trouble with those who might be offended by his bawdy side, or who might chide his literary aspirations — like his efforts to wash his hands of his own writings. In the Miller’s Prologue, for example, he ‘makes his audience responsible for whether they enjoy his work.’

‘In the Prologue to The Legend of Good Women (c. 1387), the God of Love and his wife Alceste chastise Chaucer with a list of his works (Chaucer later updated the Prologue to include recent works, assuring the record was correct), and the Man of Law’s Prologue from The Canterbury Tales offhandedly abuses Chaucer’s rhyme before giving another catalogue. The ‘retraction’ at the Tales’ end, in which Chaucer — apocryphally from his deathbed — asks God to forgive him for his ‘translaciouns and enditynges of worldly vanitees,’ fulfils the same role. …

“In her painstaking biography Chaucer: A European Life (2019), Turner argues that Chaucer’s writings must proceed from some sort of democratic impulse. … This, perhaps, is Chaucer’s great innovation in our literature, surpassing even the invention of the decasyllabic English line that found its way to iambic pentameter: a level narrative playing field, inviting interaction and discussion.”

If you’d enjoy leaving 2024 for another world, there’s lots more at the Poetry Foundation, here. No paywall.

This is interesting, because I have only negative memories of studying Chaucer in high school. And of Shakespeare I have only positive memories. I think it was because the teacher who presented Chaucer to us was not very kind and made us memorize a page of it in old English while she made fun of our pronunciation. I didn’t connect with his narratives.

LikeLike

Give him another shot?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I bet he deserves one. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person