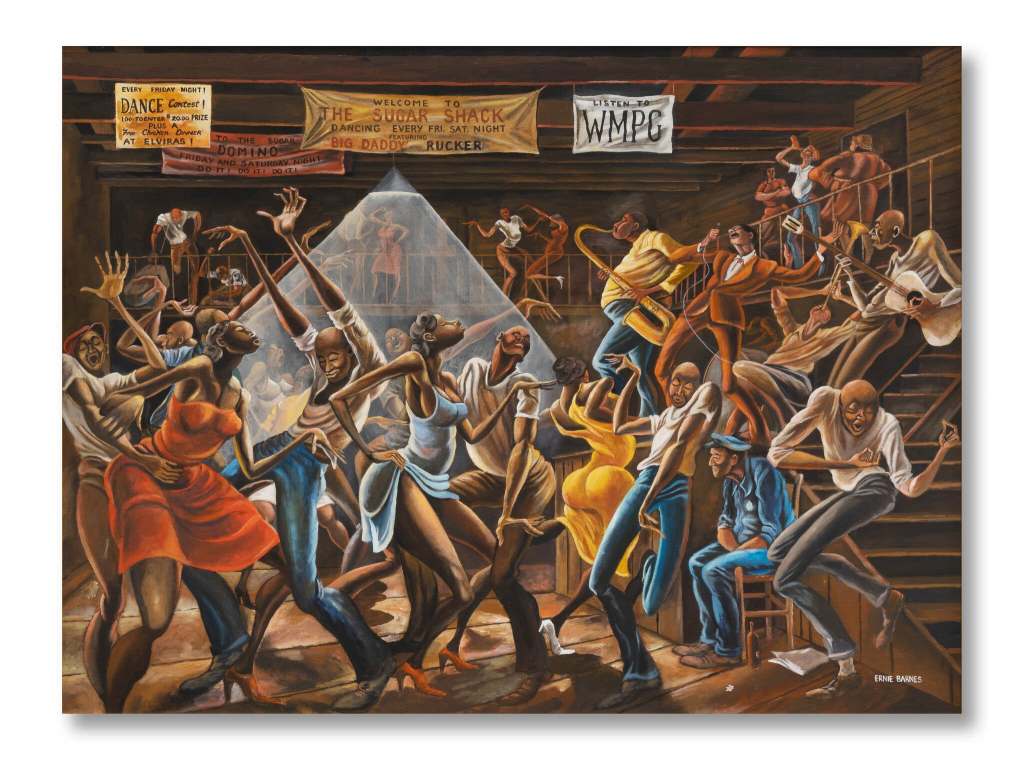

Art: Ernie Barnes.

Photo: Ernie Barnes Estate, Ortuzar Projects and Andrew Kreps Gallery.

Ernie Barnes’s “The Sugar Shack” (1976) sold well above its estimate at a Christie’s auction in 2022.

I’ve been thinking about artists whose popularity often seems to put them beyond recognition by the “academy.” Can they be taken seriously by serious people if they are popular? If their works are deliberately priced to be affordable, does that mean they are not valuable?

Adam Bradley writes at the New York Times about the long underappreciated artist Ernie Barnes, who is having “a moment” now that he has died.

Bradley writes that “in the 1970s, buying a print of Ernie Barnes’s ‘The Sugar Shack,’ the iconic 1976 dance club painting that adorns the cover of Marvin Gaye’s album released that spring, ‘I Want You,’ and appears in the credits for the classic sitcom Good Times (1974-79), required nothing more than mailing a $20 check to the artist’s West Hollywood studio.

“In 2022, the second of two originals — inspired by a childhood adventure of sneaking into a famed dance hall to watch couples drag and sway to the live performances of Clyde McPhatter or Duke Ellington — came up for auction at Christie’s, selling for $15.3 million. The buyer was the Houston-based energy trader and high-stakes gambler Bill Perkins, 54, who won a bidding war against 22 other prospects. This vast divergence of price belies a convergence of spirit: The countless individuals hanging inexpensive prints on the walls of bedrooms and barbershops share with Perkins (and no doubt with the other wealthy collectors who bid the painting up to more than 76 times its high estimate) an ineluctable desire for the nostalgia and affirmation that Barnes’s work conveys.

“Barnes, who died in 2009 at 70, left a paradoxical legacy. He was an artist of the people — most especially of Black people — selling reproductions at prices that enabled everyone to own something beautiful. He was also an artist to the rich and famous; he sold many of his original works to athletes, movie stars and musicians, from Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to Grant Hill, Diana Ross to Bill Withers, Harry Belafonte to Sylvester Stallone. He was among the most visible artists of the ’70s, with millions seeing his paintings on television each week; yet his work was excluded from major museum collections.

“The unprecedented price paid for ‘The Sugar Shack,’ Barnes’s most recognizable work, has changed everything — and nothing at all, inviting a wider (and whiter) audience to revisit an artist whose reputation among Black Americans is unassailable. More than a dozen years after his death, Barnes, long a popular painter, has become an important one, with all that term entails: a hot global market for his work (pricing out many of Barnes’s original collectors); newfound interest from museums; and, most immediately, a major gallery exhibition scheduled for next year at Ortuzar Projects in New York, which will invite a deeper look at Barnes’s varied career.

“Ernest Eugene Barnes, Jr., was born in Durham, N.C., in 1938, and grew up in a segregated neighborhood known as the Bottom. His father was a shipping clerk for Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company and his mother worked as a domestic.

“In his 1995 memoir, From Pads to Palette, Barnes recalls using sticks as a child to sketch undulating lines ‘in the damp earth of North Carolina.’ By the time he was in high school, Barnes had grown close to his full height of 6 feet 3 inches and finally gave in to the football coach’s entreaties for him to play offensive lineman.

“By 1956, he had 26 college scholarship offers; he enrolled at the historically Black North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University), where he studied art. Though Barnes found support for his artistic endeavors on campus (he sold his first painting, ‘Slow Dance,’ a precursor to ‘Sugar Shack,’ for $90, to the recent alum and Boston Celtics guard Sam Jones), he often faced bigotry beyond it, and this led him away from art. The Baltimore Colts selected Barnes in the 1960 N.F.L. draft, and he played for four other teams in a six-year career before leaving the game because of the physical toll of injury and the psychic toll of delaying his true calling as a painter. …

“Barnes worked for a short period in the off-season as a door-to-door salesman, and as a construction worker building crypts. Then, with the endorsement of the business mogul and San Diego Chargers owner Barron Hilton, Barnes crashed the American Football League owners’ meeting to make a pitch to become the first official painter of a professional sports franchise. Many of the owners ignored him; one heckled him.

“But another, Sonny Werblin of the New York Jets, offered to pay him a player’s salary to become the team’s official painter. After a year, Barnes had built up enough of a portfolio for Werblin to sponsor Barnes’s first solo show, at the famed Grand Central Art Galleries in Midtown Manhattan. Barnes was 28. His work, which rendered football as modern-day gladiatorial spectacle, was stylized and dramatic. One could see within it the stirrings of his mature aesthetic: his loose and gestural handling of human form, his passion for portraying bodies in motion.

“His athleticism was far from incidental to his art. … Barnes understood the human body not from the outside in, in the studied manner of a draftsperson, but from the inside out, through his knowledge of how bone, muscle and ligament move in concert. …

“Barnes’s 1966 New York show might have marked his triumphant emergence into the artistic mainstream. Instead, it was greeted with indifference. ‘It was a shock to me,’ Barnes said decades later. If the art world was going to reject him, then he would reject it. ‘When I found out that I didn’t have to belong, really, to that world, he said, ‘that was much more assuring to me as a human being.’ …

“He expanded his subject matter to suit a broader audience, directing his eye for physicality toward everyday life. What does it look like to walk down the street with swagger, to hoist a heavy bag at day’s end, to jump double Dutch? Inspired in part by the Black Is Beautiful movement of the photographer Kwame Brathwaite and others, Barnes began producing works that would comprise a show titled ‘The Beauty of the Ghetto. It opened in 1972 at what was then known as the California Museum of Science and Industry and traveled the country for seven years. …

“In 1973, he met with the television producer Norman Lear, who was preparing a new program provisionally titled The Black Family. Lear was so taken with Barnes that he proposed not only using Barnes’s paintings on the show but also making the family’s eldest child, J.J. (who’d be portrayed by the actor Jimmie Walker), an artist himself. …

“ ‘His work is really about joy and positivity,’ says Ales Ortuzar, 47, who along with Andrew Kreps co-represents Barnes’s estate. ‘Those are two things that have traditionally been dismissed in the art world.’ Indeed, irony has no place in Barnes’s artistic worldview. His canvases are domains of earnestness and striving, of unalloyed celebration and pride. …

“ ‘There are a number of folks who will say, “Oh, his work has a $15 million price tag on it,” ‘ says [Derrais Carter, 39, a professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona and the curator of the Barnes exhibition at Ortuzar Projects]. ‘ “Let me pay attention to it.” And I’m like, “Well, Black folks never needed no $15 million to own that work.” It’s been in dens, college dorm rooms, on faded album covers, the whole nine. These [paintings] are like talismans, anchors of home.’ ”

More at the Times, here.

Now I want to read his autobiography/memoir! Thanks for yet another terrific story!!!

LikeLike

So interesting how football played into his art–among other interesting aspects.

LikeLike

Important African American artist; loved seeing his work on Good Times. Sorry to hear of his acceptance in the art scene only after his death. Sounds like the people he considered his community always knew he was great.

LikeLike

I wasn’t watching much TV at the time, so he is new to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person