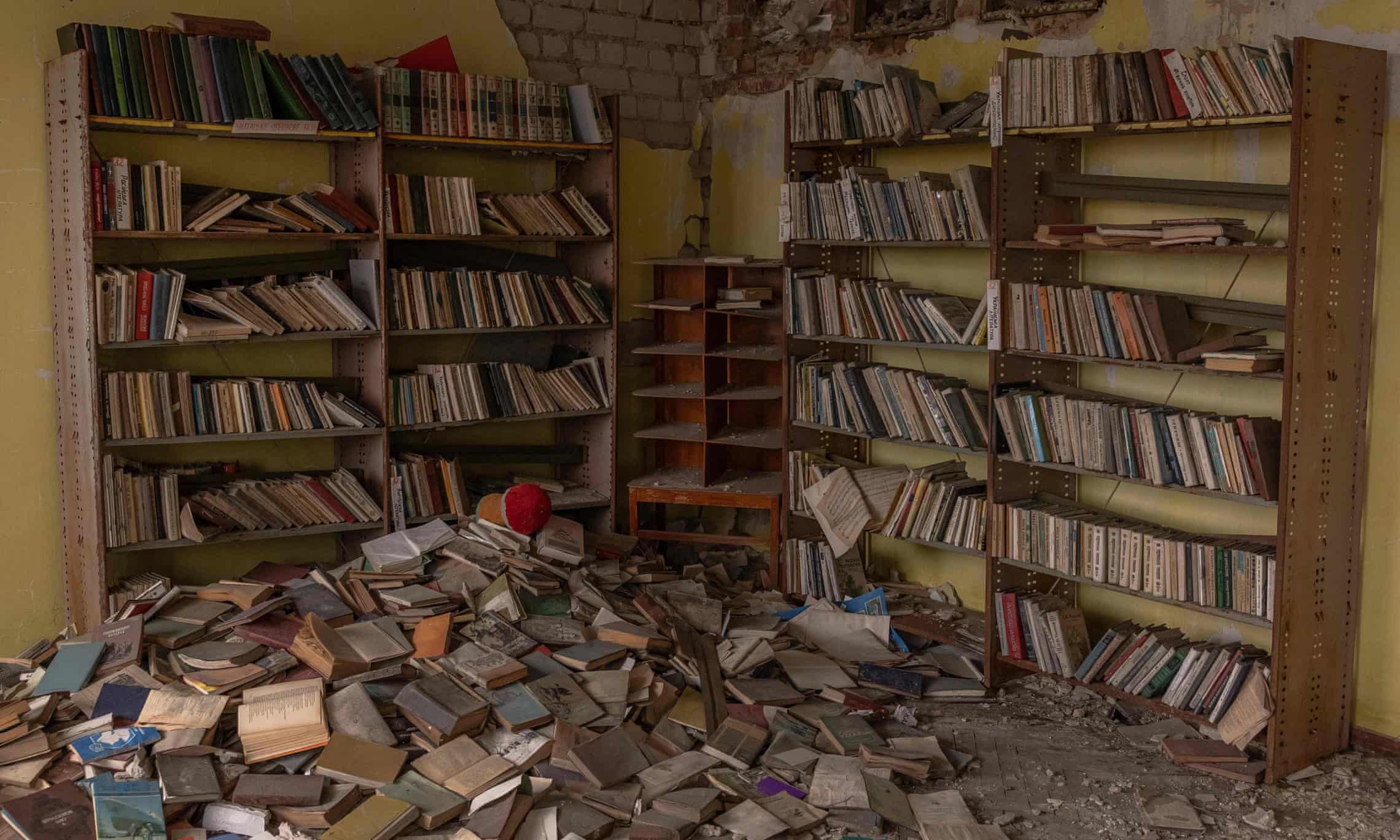

Photo: Roman Pilipey/AFP/Getty Images.

The house of culture in the village of Posad-Pokrovske in southern Ukraine was badly damaged in attacks by Russian forces in 2022.

There’s a secret teen book club in occupied Ukraine, where the “official” schools teach Russian propaganda. Confided one student, “They don’t teach us knowledge at school, but to hate other Ukrainians.”

Peter Pomerantsev and Alina Dykhman report at the Guardian, “It must be one of the most dangerous book clubs in the world. Before they can feel safe enough to talk about poetry and prose, 17-year-old Mariika (not her real name) and her friends have to first ensure all the windows are shut and check there is no one lurking by the flat’s doors.

“Informants frequently report anyone studying Ukrainian in the occupied territories to the Russian secret police. Ukrainian textbooks have been deemed ‘extremist’ – possession can carry a sentence of five years. Parents who allow their children to follow the Ukrainian curriculum online can lose parental rights. Teens who speak Ukrainian at school have been known to be taken by thugs to the woods for questioning.’

“That is why the book club never meets with more than three people – any extra members would pose further risk of being discovered.

“Apart from the danger, there is another challenge: finding the books themselves. In the town where Mariika lives, the occupiers have removed and destroyed the Ukrainian books from several libraries – nearly 200,000 works of politics, history and literature lost in one town alone.

“So Mariika and her friends have to use online versions – careful to scrub their search history afterwards. The authorities like to seize phones and computers to check for ‘extremist’ content.

“Among the poems and plays Mariika’s book club likes to read are those of Lesya Ukrainka, the 19th-century Ukrainian feminist and advocate of the country’s independence under the Russian empire.

“In 1888 Ukrainka also formed a book club, in tsarist-era Kyiv, at a time when publishing, performing and teaching in Ukrainian was banned. Ukrainka’s works, in turn, explore the 17th-century struggle of Ukraine for independence from Moscow.

“In the dramatic poem ‘The Boyar Woman,’ the heroine chides a Ukrainian nobleman who has come under the cultural influence of Muscovy and praises a humiliating peace with the tsar that has ‘calmed’ Ukraine: ‘Is this peace,’ she asks, ‘or a ruin?’ …

“Over the centuries, Russia’s tactics have adapted. During the Russian empire, Ukraine was conquered, and its language and literature were suppressed. At other times, the Kremlin used mass starvation and the mass murder of intellectuals, as in the Holodomor, the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s, when about 4 million people were killed by Stalin’s policies.

“During the later years of the Soviet Union, the approach was subtler: some Ukrainian schools and a small amount of publishing were allowed but if you wanted to prosper, you had to speak Russian. Ukrainian poets and activists who asked for more national rights were sent to the last labour camps as late as the mid-1980s. …

“As it has done for centuries among its colonies, the Kremlin is changing the population on the ground by deporting local people and importing new ones with no connection to Ukraine. Since 2014, more than 50,000 Ukrainians have been forced to leave Crimea and about 700,000 Russian citizens brought in, many of them with military and security service backgrounds. …

“More than 19,000 children have been forcibly removed to Russia to indoctrinate them and break their connection to Ukraine. … There are the 1.5 million children who are still inside the occupied territories, but who are being forced to abandon their Ukrainian heritage, attend military youth groups and ultimately be conscripted into the Russian army. …

” ‘They don’t teach us knowledge at school,’ said Mariika, ‘but to hate other Ukrainians. They’ve taken down all Ukrainian symbols and have hung portraits of Putin everywhere. History is all about “great Russia” and how it’s always been under attack by others.’ …

“Part of what keeps Mariika’s book club going is the desire for people outside the occupied territories to realize that there are people fighting for their right to exist as Ukrainians. Not all the books the club has been reading are overtly political. Sometimes they enjoy reading books that are just about normal life of young women in Ukraine – about dating and shopping.

“These tales take on a greater meaning in the occupied territories – a way to stay in touch with everyday life in the rest of the country. Novels have always helped to make you feel part of the community, of a nation.

“But still there is no getting away from the all-too-relevant ideas of Ukrainka’s writing. One of her main themes was to meditate on the relationship between personal freedom – the freedom of the imagination and to define your life – and the political freedom of the nation. ‘Whoever liberates themselves, shall be free,’ she wrote.

“Mariika’s book club makes those words real every day.”

More at the Guardian, here.

Leave a comment. Website address isn't required.