Photo: VAN

How’s your Latin? It might help in appreciating this post about 16th century classical music. Then again, you don’t need Latin to understand that a black classical composer from that long ago should not be forgotten. Garrett Schumann reports the story at an online magazine called VAN.

” ‘Only then can his creative genius begin redounding, as it should, to the glory of Black music history,’ writes the musicologist Robert Stevenson in his 1982 article, ‘The First Black Published Composer.’

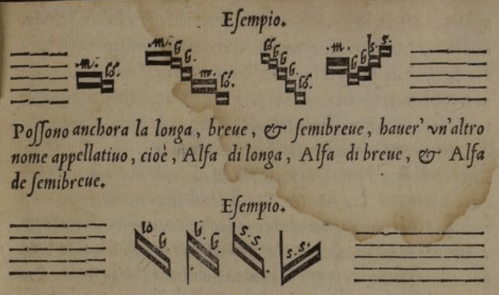

“Stevenson’s subject was Vicente Lusitano (ca. 1520-ca. 1561), an African-Portuguese priest and musician who enjoyed an international career. Stevenson heralds works like the motet ‘Heu me domine”’ (1551), which exemplifies the composer’s unusual embrace of chromatic counterpoint. …

“Of Lusitano’s compositions, ‘Heu me domine’ has received the most attention from modern scholars and performers, but it is not the only example of his remarkable creativity. In a 1962 essay, Stevenson reproduces a passage from Lusitano’s motet ‘Regina coeli’ to highlight its adventurous chromatic writing, and notes that other works in Lusitano’s 1551 motet collection feature extremely uncommon combinations of accidentals. Musicologist Philippe Canguilheim, in a 2011 essay regarding Lusitano’s unpublished counterpoint treatise, writes that Lusitano is ‘particularly tolerant’ of dissonance, a practice he justifies in the text by citing Pythagoras and Boethius.

“The alluring counterpoint and voice leading of ‘Heu me domine’ connect to improvisation techniques which Lusitano outlines in his counterpoint studies. As Canguilheim notes, these works make pioneering arguments regarding canons and the productive interplay between composition, free improvisation, and structured improvisation.

“ ‘Heu me domine’ is one of just two pieces in Lusitano’s output that 20th-century scholars have transcribed into modern notation — until last month, it was the only piece of his to be recorded. The other work, a 1562 madrigal called ‘All’hor ch’ignuda,’ was recently arranged for woodwind trio and recorded by multi-instrumentalist Misty Theisen. …

“Ironically, Lusitano’s obscurity originates in the most famous episode of his career. In 1551, while in Rome, Lusitano was drawn into an aesthetic dispute by fellow composer Nicola Vicentino (1511-ca.1576), an argument which gained so much attention that a Vatican tribunal convened to issue a verdict. Lusitano won, and Vicentino paid a fine, but, for years afterward, Vicentino published egregiously disingenuous descriptions of the proceedings with the aim of damaging Lusitano’s reputation.

“A 17th-century source in Rome attests that Lusitano’s name was scratched off copies of the widely-published introduction to his counterpoint treatise, and it is plausible he faced other reprisals that went undocumented. These developments likely led to Lusitano’s relocation to Germany sometime after 1553, where he converted to Protestantism, married, and continued his career until his death. …

“Lusitano’s obscurity also shows the influence of collective action on a composer’s legacy. Vicentino worked hard to distort and erase Lusitano’s achievements, but these efforts only retained their impact because other scholars and artists have — perhaps out of convenience or ignorance — uncritically reproduced Vicentino’s version of the facts.

“Whether any of these developments are related to racial bias is difficult to prove. Nevertheless, composers with historically excluded identities, like Lusitano, have been extraordinarily underserved by institutions of classical music performance and scholarship. Reports from Bachtrack.com analyzing programming from more than 160,000 classical performances around the world between 2014 and 2019 show a population of just 15 white men constitute the 10 most-programmed composers in each of those five performance seasons. Recent research by Philip Ewell exploring the intersection of music theory and critical race theory also compellingly asserts that institutionalized music scholarship is structured in a way that ignores the achievements of women and people of color.”

It’s a long article, but interesting. Read it here.

Hat Tip: Arts Journal.

Douglas Lawrence leads the Australian Chamber Choir at St Martin-in-the-Fields in “Heu me domine” (1551), by Vicente Lusitano, the first published Black classical composer.