Photo: Sky2105, CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons.

Qatar University campus features a new wind catcher design built into the architecture. The science behind it is borrowed from 12th C Iran.

Here’s a “cool” air-conditioning concept that was new to me but apparently known in Iran for centuries.

Durrie Bouscaren reports at radio show The World, “As a kid, radio producer Sima Ghadirzadeh spent her summers in one of the hottest places on earth — the desert city of Yazd, Iran. … Here, intricate wind-catching towers rise above the alleyways — they’re boxy, geometric structures that take in cooler, less dusty air from high above the city and push it down into homes below.

“This 12th-century invention — known as badgir in Persian — remained a reliable form of air-conditioning for Yazd residents for centuries. And as temperatures continue to rise around the world, this ancient way of staying cool has gained renewed attention for its emissions-free and cost-effective design.

“Wind catchers don’t require electricity or mechanical help to push cold air into a home, just the physical structure of the tower — and the laws of nature. Cold air sinks. Hot air rises.

“Ghadirzadeh said she can remember as a child standing underneath one in her uncle’s living room in Yazd.

“ ‘Having been outside in the heat, and then suddenly, going inside and being right under the wind catcher and feeling the cool breeze on you, was so mysterious,’ Ghadirzadeh said.

“Temperatures in Yazd can regularly reach 115 degrees Fahrenheit. But somehow, it was bearable, Ghadirzadeh said. … Historians say wind catchers are at least 700 years old. Written records in travelers’ diaries and poems reference the unique cooling structures.

“ ‘From the 13th century, we have references to the wind catcher — by some estimates, they were in use in the 10th and 11th centuries,’ said Naser Rabbat, director of the Aga Khan program for Islamic architecture at MIT.

“Most wind catchers only cooled the air by a few degrees, but the psychological impact was significant, Rabbat said. They soon appeared all over the medieval Muslim world, from the Persian Gulf to the seat of the Mamluk empire in Cairo, where they are called malqaf.

“In Iran, the wind catcher is a raised tower that usually opens on four sides because there’s not a dominant wind direction, Rabat said. The ones in Cairo are ‘extremely simple in form,’ usually with a slanted roof and a screen facing the direction of favorable wind, he added.

“Over time, wind catchers became symbols of wealth and success, growing increasingly elaborate. Homeowners would install intricate screens to keep out the birds. Water features and courtyard pools could bring the temperature down even more.

“ ‘They would even put water jars made out of clay underneath — that would cool the air further,’ Rabbat said. ‘Or, you can put a wet cloth and allow the breeze to filter through, and carry humidity.’

“Many of the older techniques that kept life comfortable in the Persian Gulf fell out of favor after World War II, said New York and Beirut-based architect Ziad Jamaleddine. …

“Those shaded walkways, created by overhanging buildings and angled streets so beloved in historic cities like Yazd, were no longer considered desirable.

“ ‘What they did is they substituted it with the gridded urban fabric city we are very familiar with today. Which perhaps, made sense in the cold climate of western Europe,’ Jamaleddine said. But in a place like Kuwait or Abu Dhabi, mass quantities of cool air are necessary to make this type of urban planning comfortable.

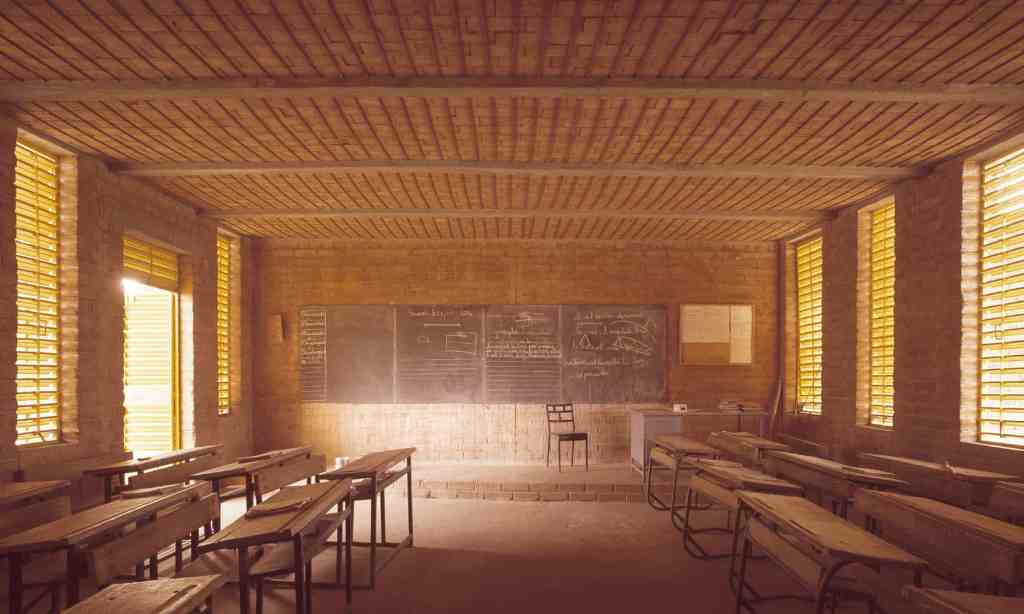

“Attempts to re-create wind catchers occurred during the oil crisis of the 1970s and 1980s in cities like Doha, where the Qatar University campus incorporates several equally distributed wind towers. But these projects became less common when oil prices returned to normal. Wind catchers are not easy to replicate without a deep understanding of the landscape and environment, Jamaleddine said. …

“Today, air conditioners and fans make up more than 10% of global electricity use, according to the International Energy Agency. The air conditioners are leaking refrigerant into the atmosphere, which acts as a greenhouse gas. And they no longer function when the power goes out — as seen this summer during extreme heat waves across the world.

“Architect Sue Roaf thinks it’s ‘almost criminal’ to build structures that continue to rely on air-conditioning, knowing its impact on the climate. Roaf focuses on climate-adaptive building and chose to build her home using the same principles of ventilation and insulation that she learned while studying the wind catchers of Yazd.”

More at The World, here. No paywall.