Photo: Edwards’s Botanical Register.

The Phillip Island glory pea, which once grew in Australia, is a leading candidate for de-extinction, according to e360.

Do you get visions of Frankenstein’s monster when you hear about reversing extinction? Maybe we start with plants, but then what? Dinosaurs?

Well, it’s hard for me to be against anything that extends knowledge, so I’m keeping an open mind about the Yale Environment 360 report on the de-extinction of plants.

Janet Marinelli writes, “In January 1769, botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander found a daisy in Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. Later named Chiliotrichum amelloides, it is one of a thousand plant species unknown to European scientists that the two men collected during Captain Cook’s first voyage on the HMS Endeavor. … The plant was dried and pressed for future study. Today, the 254-year-old specimen is among the almost 8 million preserved plants in New York Botanical Garden’s William & Lynda Steere Herbarium.

“ ‘When a plant goes extinct,’ says Giulia Albani Rocchetti, a postdoctoral researcher at Roma Tre University and the lead author of the paper, ‘we don’t just lose a species, we lose a member of a habitat community with a specific role and relations with other species; … we lose genes which could have provided insight into the species and its community and yielded new pharmacological compounds and other products.’ …

“For nearly five centuries, herbaria have helped botanists identify, name, and classify the world’s floral diversity. Now these vast botanical libraries are being tapped to try to create a new chapter in the 500-million-year history of Earth’s terrestrial plant life. In Nature Plants in December, an international group of biologists published the first-ever list of globally extinct plants they believe can be returned from the dead, using seeds available in herbarium specimens. …

“In recent decades, the seeds of rare and imperiled species have been preserved in seed banks at low humidity and temperatures that ease the embryos inside into a kind of state of suspended animation to maximize their longevity. However, species already lost remain only as specimens in the collections of dried and pressed plants known as herbaria, and only in some (lucky) cases. … Only a few of these plants happened to be in fruit and in seed when they were collected. And even when herbarium seeds are discovered, there is no easy way to tell if the embryos inside are dead or lying dormant, waiting to sprout when conditions are right. …

“Abby Meyer, executive director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International in the United States, points to the rise in recent decades of the field of bioinformatics, which has transformed the trove of biodiversity information once locked up in natural history collections — such as herbarium specimens of extinct plants that contain seeds — into browsable digital databases. New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), for example, began digitizing its herbarium specimens in the mid-1990s, and today some 4 million, or about half of its preserved plants, have been scanned and can now be called up on a computer screen by anyone around the globe.

“Data aggregators such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility provide researchers looking for seeds with instant access to millions of scanned specimens, along with associated ‘metadata’ such as the GPS coordinates where the plants were collected. At the same time, scientists have been refining in vitro embryo rescue techniques, increasing the odds that old or weak seed embryos can grow into viable plants. …

“While attempts to de-extinct the dodo, the woolly mammoth, and other charismatic megafauna continue to grab headlines, they would result at best in a hybrid, genetically engineered animal — a proxy of an extinct species. By contrast, recovering plants by germinating or tissue-culturing any surviving seeds or spores preserved in herbaria would result in the resurrection of the actual species. …

“One of the biggest hurdles is figuring out how to germinate the precious few seeds of often genetically unique plants found only on dried specimens. There is little margin for error, and before attempting to germinate the extinct species itself, scientists must perfect methods for germinating seeds of any closely related species that survive. …

“In December 2019, Giulia Albani Rocchetti sat in Florence’s Central Herbarium, marveling over the remains of Ranunculus mutinensis, an endemic buttercup that once grew in moist floodplain forests of the Po River, as it threads through northeastern Italy. … It was a thrill for her to find not just one but two Ranunculus specimens with numerous mature fruits called achenes. She then spent months at her desk in Rome, blowing up digitized images of extinct plants from herbaria across the globe on her computer screen in the improbable search for seeds.

“She was also spurred on by the knowledge that some seeds have the astonishing ability to survive adverse conditions and sprout after decades, even centuries — such as the Judean date palm, which a team of scientists successfully germinated in 2005 from a 2,000-year-old seed. …

“Albani Rocchetti and colleagues … identified 556 specimens that contained seeds, representing 161 of the extinct plant species [and] proceeded to devise a pioneering roadmap for prioritizing species for de-extinction. Assuming that species whose close kin produce long-lived seeds and newer specimens are the most likely to contain seeds that survive, they combined data on the seed behavior and longevity of closely related plants, as well as the age of each specimen, to create a DEXSCO, or best de-extinction candidate score for each species. …

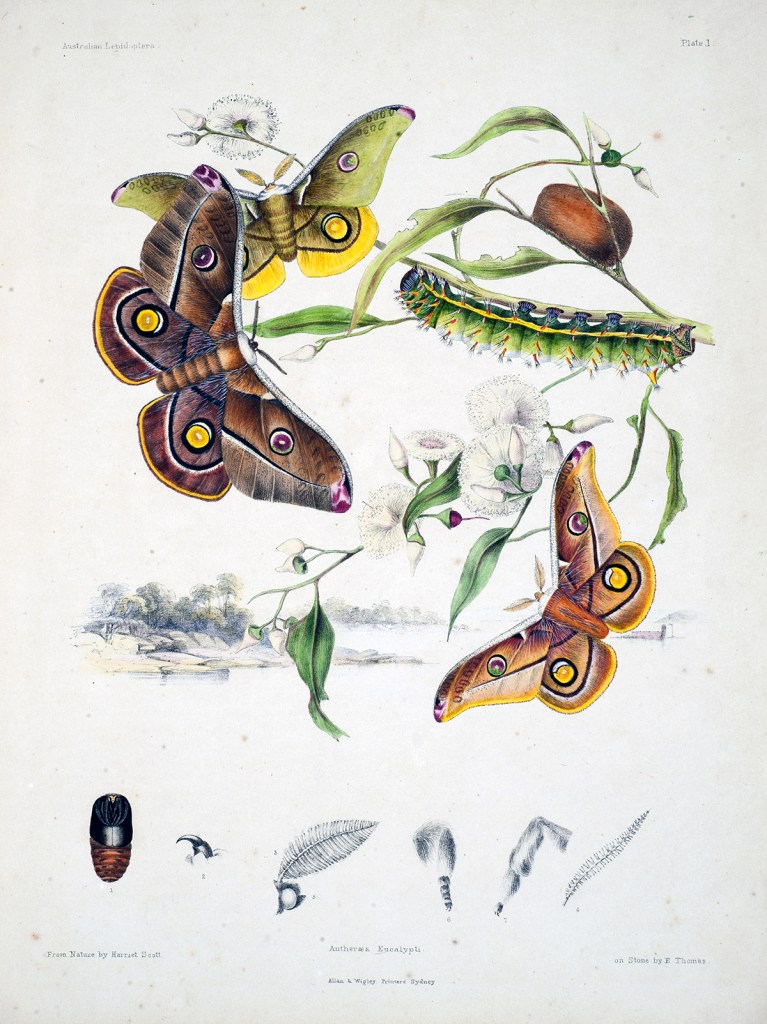

“Streblorrhiza speciosa, a spectacular member of the pea family, was [so] unique that it is considered the only member of its genus, or closely related group of plants. The species’ striking cascades of pink blossoms clambered exuberantly over trees on Phillip Island in the Pacific Ocean east of Brisbane, Australia. Collected in 1804 by Austrian botanist Ferdinand Bauer, the Phillip Island glory pea was an instant hit in Europe, coveted by every wealthy family with a conservatory. Meanwhile, however, Phillip Island was being overrun by pigs, goats, and rabbits introduced by British officers overseeing a nearby penal settlement, leaving barely a scrap of the remote island’s unique vegetation, and the glory pea was never seen in the wild again. …

“The glory pea is now presumed extinct, but at number three is near the top of the list of recommended de-extinction candidates. …

“Another challenge of plant de-extinction is the lack of financial support for pursuing it. But on the bright side, plant de-extinction has not kicked up the controversy surrounding attempts to resurrect, say, the wooly mammoth or passenger pigeon. ‘For whatever reason, the human brain doesn’t seem to be as concerned about plants as about animals,’ Knapp says. ‘But in this case, we’re literally just germinating seed. We’re not reconstructing a genome. And that’s way less intimidating. Everyone can understand that.’ “

More at e360, here. No firewall.