Photo: Lane Turner/Globe Staff.

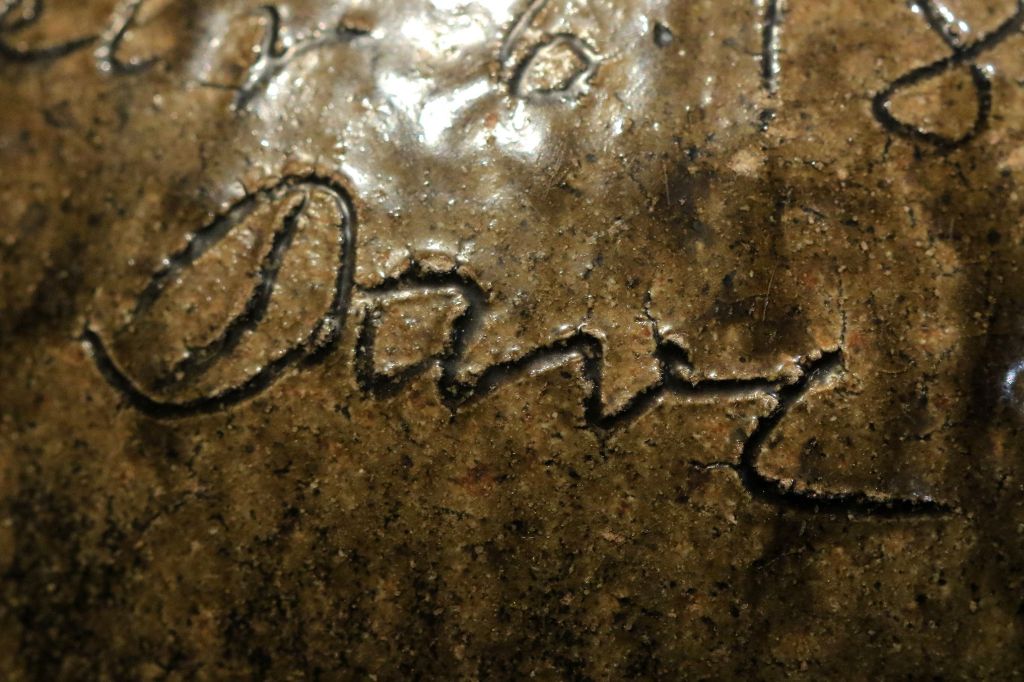

“Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” an exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, presents 12 works by enslaved potter David Drake. Above, David Drake’s signature, “Dave,” on a storage jar from 1858.

Today’s story is about an enslaved potter and the descendants who found him 150 years later. It is so painful to read about him being “bought.” You really have to wonder about the depths to which humanity sometimes descends.

Malcolm Gay reports at the Boston Globe, “In 1857, an enslaved potter in South Carolina’s Old Edgefield district carved a brief poem into a pot he’d turned in the mid-August heat.

“The potter had been bought and sold by a series of owners by then. He’d lost a leg, but his gifted hands won him local renown: His expert work with clay ensured he would be kept in the district known for its stoneware, even as his family was torn from him at auction.

“Using a sharpened tool, he etched into the jar’s shoulder: ‘I wonder where is all my relation/Friendship to all — and every nation.’ The potter then added his enslaver’s initials, the date, and, finally, his own name: ‘Dave.’

“In that simple act, the man, long known as Dave the Potter, and later David Drake, was not only wondering about his lost family: He was committing an extraordinary act of defiance in pre-Civil War South Carolina, indelibly asserting his existence in an age that sought to obliterate the humanity of Black people.

“Originally created to store meats and other foods, Drake’s 40 or so poem jars are today highly sought after by museums. His inscribed vessels routinely fetch six figures at auction, and his stoneware features prominently in ‘Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,’ an exhibition featuring enslaved potters [at Boston’s] Museum of Fine Arts.

“Perhaps most significantly: More than 150 years after Drake composed his mournful verse, researchers appear finally to have found his direct descendants.

“ ‘He was sending these messages,” said Daisy Whitner, 84, whom genealogists have identified as Drake’s great-great-great-granddaughter. ‘He wanted people to know: I’m a human being; treat me as such.’

“Now in their mid-70s and 80s, Whitner and her three siblings, Pauline Baker, John N. Williams, and Priscilla Ann Carolina, believed for most of their lives that their known family tree began in Aiken, S.C. They hadn’t known they’d had family in Edgefield. They’d certainly never heard of David Drake.

“But that changed in 2016, when April Hynes, an independent genealogist and researcher who’s been tracking down descendants of enslaved people from the area, cold-called Whitner. By pairing historical research with publicly available documents, Hynes had determined that Whitner and her siblings were the potter’s direct descendants. …

“ ‘I don’t have a word to describe him,’ said Baker, 75, seated on a sofa in her niece’s tidy home outside Washington, D.C., a replica Drake pot placed prominently on the dining room table. …

“Seated to her right, Whitner grew emotional as she described touching one of Drake’s pots during a trip to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, which organized the exhibition with the MFA.

“ ‘It just tore me to pieces,’ she said. ‘I can’t stop reading and reading, trying to dig more and more.’

“The family has read nearly everything published about their ancestor, as they puzzle over his poems, searching for possible meanings and seeking clues about his life.

“Whitner is haunted by a particular jar Drake created and inscribed in 1836. It reads: ‘horses mules and hogs —/all our cows is in the bogs —/there they shall ever stay/till the buzzards take them away.’ ‘He’s using farm animals rather than to say slave,’ she said. …

“The [family] had mixed emotions when Hynes first called them with the news about Drake, but soon they were traveling down to Edgefield with around 30 family members to take part in celebrations to honor the potter.

“ ‘It’s a joyous feeling,’ said John N. Williams, 81. ‘But then there was a sadness about it, because you thought about the atrocities that happened.’

“They appreciate how rare it is, as the descendants of slaves, to be able to read their ancestor’s thoughts — particularly while he was still in bondage. But discovering a forebear who spent most of his life enslaved has also personalized their perception of the era, wrestling as they do with the scant details, and many unknowns, of Drake’s life.

“Whitner said she’d previously avoided looking at movies about slavery because ‘my heart couldn’t take it.’

“ ‘It hurt me to my core,’ she said. ‘And I will look now.’ ”

More at the Globe, here.