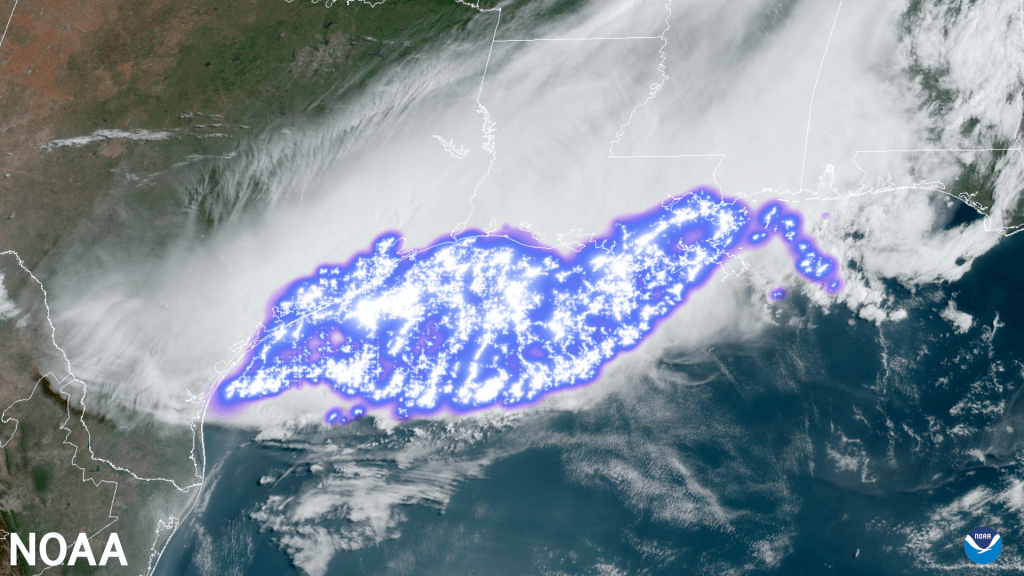

Lightning as seen from the Geostationary Lightning Mapper on NOAA’s GOES-16 satellite from April 29, 2020. The World Meteorological Organization has found that one of the lightning flashes within this thunderstorm complex was the longest flash on record, covering a horizontal distance of 477 miles.

Let’s talk about natural phenomena. Let’s talk about lightning. Can you imagine one flash covering 477 miles? That’s the record, set in 2020. Here’s Matthew Cappucci‘s January article for the Washington Post about such megaflashes.

Capupucci wrote, “The World Meteorological Organization announced on Monday that it had confirmed two new mind-blowing lightning ‘megaflash’ records. The findings, which come after careful data-checking and rigorous certification processes, include one record event that occurred over the Lower 48 states.

“On April 29, 2020, a sprawling mass of strong to severe thunderstorms produced a 477.2-mile-long lightning strike over the southern United States. It stretched from near Houston to southeast Mississippi, a distance equivalent to that between Columbus, Ohio, and New York City. …

“The WMO also identified a new world record for the long-lasting lightning flash. It lit up the skies over Uruguay and northern Argentina for 17.1 seconds on June 18, 2020. …

“ ‘These are extraordinary records from single lightning flash events,’ wrote Randall Cerveny, rapporteur of Weather and Climate Extremes for WMO, in a statement.

“Megaflashes dwarf ordinary lightning strikes. As Earth dwellers, we’re accustomed to seeing what’s going on near the ground, including conventional cloud-to-ground lightning bolts. …

“Megaflashes are different. They’re enormous. They snake through regions of high electric field and can travel for hundreds of miles while lasting more than 10 seconds. Since most storm clouds are fewer than 10 miles high, lightning can’t grow terribly long in the vertical direction. But megaflashes have plenty of space to sprawl in the horizontal.

“All megaflashes accompany MCSs, or mesoscale convective systems. MCSs are clusters of thunderstorms that often rage overnight and can occupy an area the size of several states, last for hours and stretch 750 miles or more end-to-end. They’re a staple of the spring and early summer across the southern and central United States, and are also common in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. South America’s ‘Altiplano,’ or high Andean Plateau, also brews prolific lightning-producing storms.

“Megaflashes crawl through the clouds but can produce or induce ground connections at various points. Sometimes MCSs merge, leading to amplified and more chaotic electric fields that can also be supportive of megaflashes. Covering so much real estate means megaflashes flicker for an extended duration.

“While atmospheric electrodynamicists had long since theorized about the existence of megaflashes, the scale and duration of said flashes was not well-understood until recently. …

“ ‘Detecting these extreme lightning events is very difficult due to their exceptional rarity and scale,’ wrote Michael J. Peterson of the Space and Remote Sensing Group at Los Alamos National Laboratory, in an email. ‘Your sensor has to be in just the right place at perfectly the right time to be able to see it — and the instrument has to be capable of measuring something as large as a megaflash.’ …

“That changed with the Nov. 19, 2016, launch of the GOES East weather satellite, soon followed by GOES West. Both peer down on North America from 22,236 miles above Earth and have ‘Geostationary Lighting Mappers,’ or instruments that are able to discern the infrared signal associated with a lightning flash. That allows for the tracking of cloud-to-cloud and intracloud flashes from above. …

“Megaflashes may be more common than once believed. Now that scientists are able to spot and resolve them over North America, they’re able to begin constructing a catalogue of events. One particularly impressive discharge, which eventually spanned 300 miles but was not evaluated by the WMO, occurred on the morning of Oct. 23, 2017. A thunderstorm was raging near Thackerville, Okla., a little more than an hour’s drive north of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. A lightning strike illuminated skies near the Red River — Oklahoma’s southern border — at 12:13 a.m.

“At the same time, the landscape was also aglow near Burlington, Kansas; the same massive 300 mile-long lightning bolt had illuminated an area four times larger than the state of Connecticut.”

More at the Post, here. I wonder what Philip Pullman, author of the amazing Golden Compass fantasy series, could do with this. His powerful imagination already has done a lot with electromagnetic waves.