Photo: Buda Musique via the BBC.

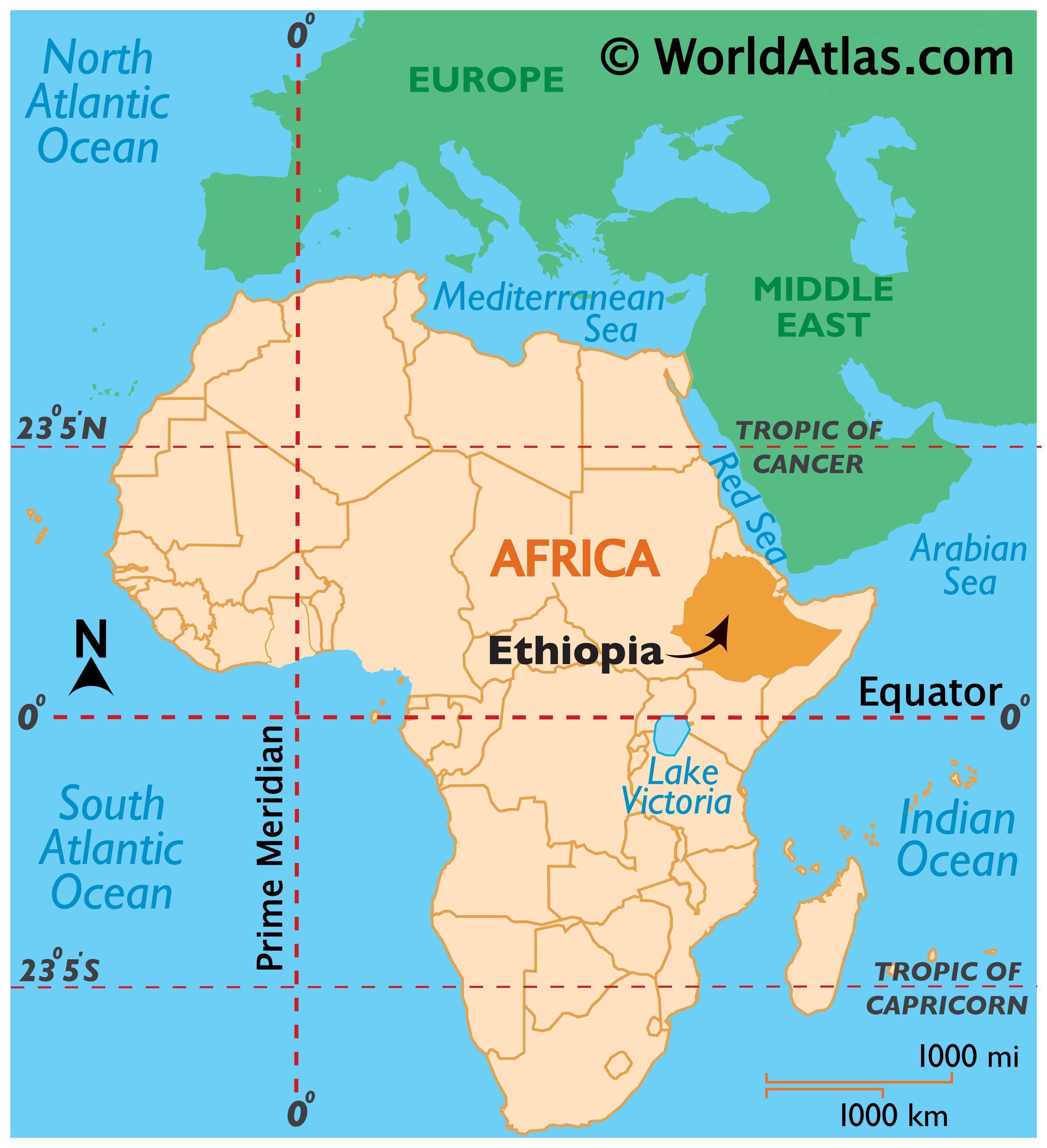

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, the composer and piano-playing nun who died March 26 at age 99. The BBC reports she led an “extraordinary life, which included being a trailblazer for women’s equality and walking barefoot for a decade in the isolated mountains of northern Ethiopia.”

Here’s a woman who had a long and fruitful life, dying at 99 after making her mark as a nun, a musician, and a proponent of women’s equality. You may be surprised to learn of the advantages a girl could have back in the day if her family was connected to Ethiopian royalty.

Brian Murphy reports at the Washington Post, “Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, a classically trained musician who once abandoned music for a hermit-like life as a nun in her native Ethiopia and later returned to the piano with a genre-defying blend of Western and Ethiopian influences, died March 26 at her convent in Jerusalem. She was 99. …

“The styles explored by Sister Guèbrou (the title Emahoy is equivalent to ‘Sister’ for a nun) were so singular in sound and structure that music scholars often puzzled over the main source of her inspiration — seamlessly mixing forms such as jazz, chamber music and rhythms from her homeland. …

“Her work was brought to a larger audience in recent years on the soundtrack for the Oscar-nominated documentary Time (2020) about a two-decade saga for an inmate and his family; and as music on the Netflix race-and-prejudice drama Passing (2021).

“Sister Guèbrou, meanwhile, spent long stretches in solitude inside the Ethiopian Monastery of Debre Genet, or Sanctuary of Paradise, in Jerusalem, where she lived since 1984 in a single room adorned with her artwork of icons and angels. …

“In her few specific comments on her musical influences, she expressed admiration for the European classical canon including Frédéric Chopin and Johann Strauss. Yet she stayed rooted in the five-note melodic runs common in Ethiopian music, while also exploring the flowing richness of Eastern Orthodox chants or the distinctly American sounds such as jazz or the old-timey snap of ragtime. …

” ‘Just within the first five or 10 seconds of the song, we have invocations of European modernism, of Ethiopian traditional music and of the links between Ethiopian Orthodoxy and a broader Judeo-Christian tradition,’ said Ilana Webster-Kogen, an ethnomusicologist at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

“ ‘Getting all of that musical information within about five seconds of listening means that comparing her to anyone else wouldn’t make sense,’ she added.

“There was a decade, however, when Sister Guèbrou played nothing at all.

“She was a rising young talent as a teen, studying for two years under Polish violinist Alexander Kontorowicz in Cairo and then was offered a scholarship to London’s Royal Academy of Music. Sister Guèbrou never made clear what happened next. For some reason, she was blocked by Selassie’s government from traveling to London.

“She was devastated. For nearly two weeks, she refused to eat. She ended up in a hospital in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. Her family feared she was near death. Weak and ailing, Sister Guèbrou said she slept for an entire day.

“ ‘When I wake up, I had a peaceful mind,’ she told the BBC in 2017. ‘I was changed. And I didn’t care for anything.’

“She left music behind. At 19, she joined the Gishen Mariam monastery in Ethiopia’s northern highlands. For the next decade, she barely left the monastery grounds, where she slept in a hut on a dried-mud bed. She noticed many of the nuns and monks were barefoot. She gave up shoes as well.

“She had already experienced huge swings in her life. She was raised in privilege in a family that had deep connections in the Ethiopian royal court, including her father’s work in diplomatic and liaison roles. She and her sister, Senedu, attended a Swiss boarding school and soaked in Western music and art.

“After Italian forces under Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Sister Guèbrou and her family were placed under house arrest and later sent to POW camps in Italy for two years. Three of her brothers were killed in the fighting. (She composed the 1963 piece, ‘The Ballad of the Spirit,’ in their memory.) …

“At nearly 30 years old, she decided to see how her fingers felt back on the piano keys. The music flowed. Now, however, it was more infused with the meditative sounds and chants from the monastery.

“ ‘I said to myself, “I have nothing. I have music,” ‘ she recalled. ‘I will try to do something with this music.’ …

“In 1974, a coup toppled Selassie and ended Ethiopia’s monarchy. Anyone favored by the ousted royal regime, including Sister Guèbrou and her family, was now under suspicion and closely monitored. When Sister Guèbrou’s mother died in 1984, she moved permanently to the monastery in Jerusalem, always seen in public in the flowing religious garb that covered her head. …

“ ‘We can’t always choose what life brings,’ she told the BBC. ‘But we can choose how to respond.’ ”

More at the Post, here.