Photo: North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy.

A monk writing by hand.

When I mentioned that string teachers have found that beginning students no longer have the finger strength for pressing down strings, Erik wondered what they had been doing in the old days that made their fingers stronger.

One thing they had been doing was writing by hand, not just swiping. Turns out we’ve lost something important.

Additionally, as Christine Rosen says at the Guardian, “In the process we are in danger of losing cognitive skills, sensory experience – and a connection to history.”

She beings by citing the autopen, “a device that stores a person’s signature, replicating it as needed using a mechanical arm that holds a real pen.

“Like many technologies, this rudimentary robotic signature-maker has always provoked ambivalence. We invest signatures with meaning, particularly when the signer is well known. … Fans of singer Bob Dylan expressed ire when they discovered that the limited edition of his book The Philosophy of Modern Song, which cost nearly $600 and came with an official certificate ‘attesting to its having been individually signed by Dylan,’ in fact had made unlimited use of an autopen. Dylan … acknowledged that: ‘using a machine was an error in judgment and I want to rectify it immediately.’

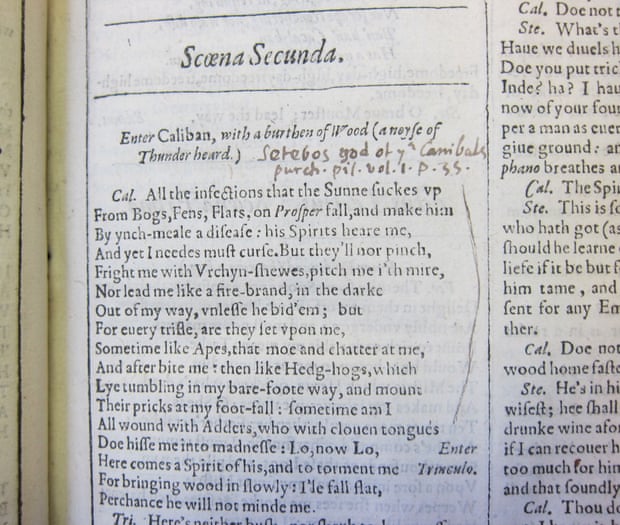

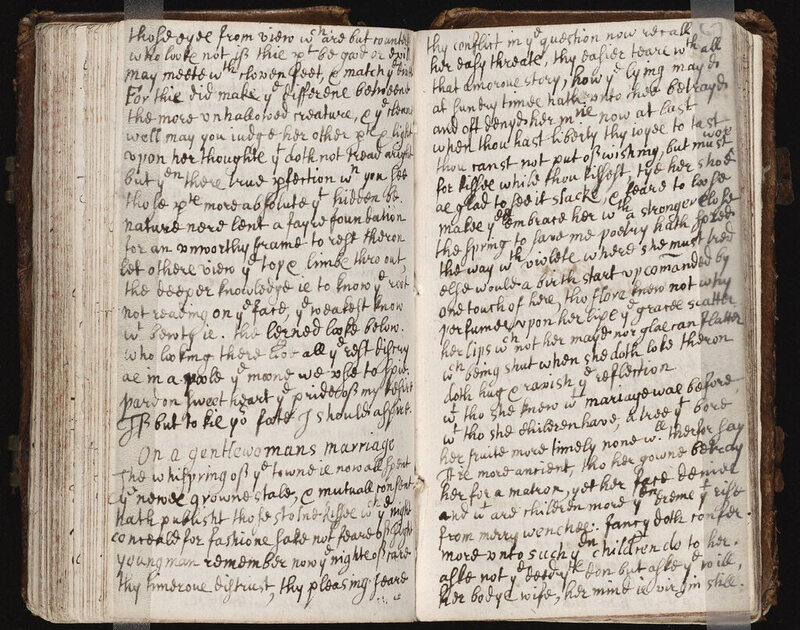

“Our mixed feelings about machine-made signatures make plain our broader relationship to handwriting: it offers a glimpse of individuality. Any time spent doing archival research is a humbling lesson in the challenges and rewards of deciphering the handwritten word. You come to know your long-dead subjects through the quirks of their handwriting; one man’s script becomes spidery and small when he writes something emotionally charged, while another’s pristine pages suggest the diligence of a medieval monk. The calligraphist Bernard Maisner argues that calligraphy, and handwriting more broadly, is ‘not meant to reproduce something over and over again. It’s meant to show the humanity, the responsiveness and variation within.’

“But handwriting is disappearing. A high-school student who took the preliminary SAT used for college admittance in the US confessed to the Wall Street Journal that ‘audible gasps broke out in the room’ when students learned they would have to write a one-sentence statement that all the work is the student’s own, in cursive, or joined-up handwriting. …

“The Common Core State Standards for education in the US, which outline the skills students are expected to achieve at each grade level, no longer require students to learn cursive writing. Finland removed cursive writing from its schools in 2016, and Switzerland, among other countries, has also reduced instruction in cursive handwriting. One assessment claimed that more than 33% of students struggle to achieve competency in basic handwriting, meaning the ability to write legibly the letters of the alphabet (in both upper and lower case). …

“Schoolchildren are not the only ones who can no longer write or read cursive. Fewer and fewer of us put pen to paper to record our thoughts, correspond with friends, or even to jot down a grocery list. Instead of begging a celebrity for an autograph, we request a selfie. Many people no longer have the skill to do more than scrawl their name in an illegible script, and those who do will see that skill atrophy as they rely more on computers and smartphones.

“A newspaper in Toronto recorded the lament of a pastry instructor who realized that many of his culinary students couldn’t properly pipe an inscription in icing on a cake – their cursive writing was too shaky and indistinct to begin with. …

“The skill has deteriorated gradually, and many of us don’t notice our own loss until we’re asked to handwrite something and find ourselves bumbling as we put pen to paper.

“Some people still write in script for special occasions (a condolence letter, an elaborately calligraphed wedding invitation) or dash off a bastardized cursive on the rare occasions when they write a cheque, but apart from teachers, few people insist on a continued place for handwriting in everyday life.

“But we lose something when handwriting disappears. We lose measurable cognitive skills, and we also lose the pleasure of using our hands and a writing implement in a process that for thousands of years has allowed humans to make our thoughts visible to one another. We lose the sensory experience of ink and paper and the visual pleasure of the handwritten word. We lose the ability to read the words of the dead.

“We are far more likely to use our hands to type or swipe. We communicate more but with less physical effort. …

“In 2000, physicians at Cedars-Sinai hospital in Los Angeles took a remedial handwriting course. ‘Many of our physicians don’t write legibly,’ the chief of the medical staff explained to Science Daily. And unlike many professions, doctors’ bad writing can have serious consequences, including medical errors and even death; a woman in Texas won a $450,000 award after her husband took the wrong prescription medicine and died. The pharmacist had misread the doctor’s poorly handwritten instructions. Even though many medical records are now stored on computers, physicians still spend a lot of their time writing notes on charts or writing prescriptions by hand.

“Clarity in handwriting isn’t merely an aid to communication. In some significant way, writing by hand, unlike tracing a letter or typing it, primes the brain for learning to read. Psychologists Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer compared students taking class notes by hand or on a laptop computer to test whether the medium mattered for student performance. Earlier studies of laptop use in the classroom had focused on how distracting computer use was for students. Not surprisingly, the answer was very distracting, and not just for the notetaker but for nearby peers as well.

“Mueller and Oppenheimer instead studied how laptop use affected the learning process for students who used them. They found that ‘even when laptops are used solely to take notes, they may still be impairing learning because their use results in shallower processing.’ In three different experiments, their research concluded that students who used laptop computers performed worse on conceptual questions in comparison with students who took notes by hand. … We retain information better when we write by hand because the slower pace of writing forces us to summarize as we write, as opposed to the greater speed of transcribing on a keyboard. …

“Researchers worry that abandoning the pen for the keyboard will lead to any number of unforeseen negative consequences. ‘The digitization of writing entails radical transformations of the very act of writing at a sensorimotor, physical level and the (potentially far-reaching) implications of such transformations are far from properly understood,’ notes Anne Mangen, who studies how technology transforms literacy. …

“It is popular to assume that we have replaced one old-fashioned, inefficient tool (handwriting) with a more convenient and efficient alternative (keyboarding). But like the decline of face-to-face interactions, we are not accounting for what we lose in this tradeoff for efficiency, and for the unrecoverable ways of learning and knowing, particularly for children. A child who has mastered the keyboard but grows into an adult who still struggles to sign his own name is not an example of progress.

As a physical act, writing requires dexterity in the hands and fingers as well as the forearms.

“The labor of writing by hand is also part of the pleasure of the experience, argues the novelist Mary Gordon. ‘I believe that the labor has virtue, because of its very physicality.’ “

Very interesting piece. Read more at the Guardian, here.

Photo: Beinecke Flickr Laboratory/CC BY 2.0

Photo: Beinecke Flickr Laboratory/CC BY 2.0