Photo: Isa Farfan/Hyperallergic.

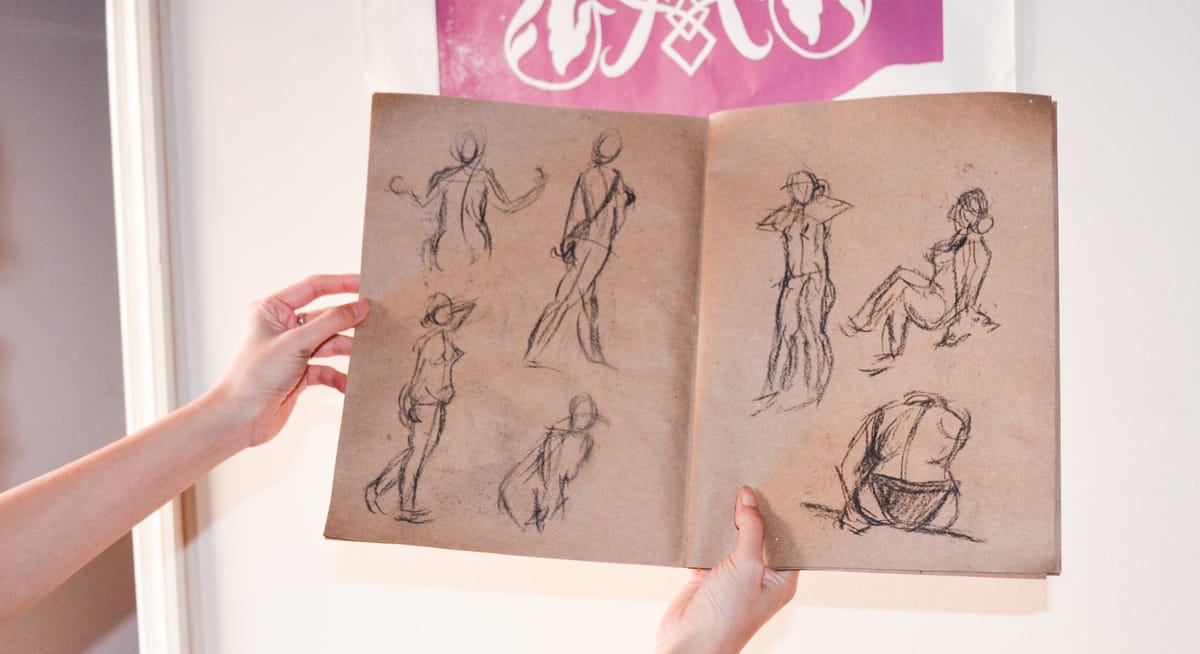

A series of sketches created by Melody Lu during a life drawing session.

I’ve always been fascinated by how many different kinds of jobs there are in the world, but I’ve seldom delved into what it feels like to be in an unusual job. I know how it feels to be a waitress, a school teacher, and an editor, and that gives me sympathy for workers in those fields. Other people feel the same. It seems that generous tippers in restaurants have often known firsthand what it means to be on the other end.

Now Isa Farfan at Hyperallergic has given us a glimpse into the life of art models. It was a revelation to me.

“Aaron Bogan, a professional art model and illustrator originally from New Jersey, moved to New York City last year from the Bay Area, attracted in part by what he described as an ‘abundant’ modeling scene. For the past 20 years, Bogan has been a life drawing model, a physically demanding contract-based profession.

“ ‘Figure models are the blue-collar workers of the arts,’ Bogan said. ‘I don’t think anybody knows the amount of physicality and mental fortitude it takes to do what we do on stage.’

“In California, Bogan was part of the Bay Area Models Guild, which claims to represent some of the highest-paid figure models in the country, negotiating a minimum $50 hourly wage for their models. Though Bogan said he finds himself working more hours in New York City than ever before, he is earning just $22 an hour, above the minimum wage but below the living wage at standard full-time hours. On the night he spoke to Hyperallergic, Bogan had worked intermittently from 9 am until around 10 pm. He said he models six or seven days a week.

“A typical three-hour open drawing session begins with artists filing into a studio arranged expectantly toward an area where a model will disrobe. Nude, the model contorts into poses, ranging from sitting cross-legged on the stage to elaborate stances involving chairs, poles, and, for Bogan, katana swords. The relationship between the model and the student is demarcated by a stage, and for the artist, tucked behind a sketchbook or easel, the hours go by quickly, almost prayerfully. For the model, the work can be a gratifying form of artistic expression or meditation, but the postures are physically exerting. Standing poses, Bogan said, led him to develop a painful ulcer on his leg, which required a $430 emergency room visit earlier last October. He went back to work the next day.

“ ‘We’ve all been through pain on the inside and outside, and we bring it all on the stage,’ Bogan said. ‘We’re all smiling, and we’re all doing everything on stage, but nobody knows that when you’re on stage, it looks like you’re stoic, but on the inside, you’re breaking.’

“Despite playing a consequential role in visual arts institutions across the country, art models, also known as figure models or life drawing models, are struggling to cobble together a living between unreliable hours and varying wages, according to nine models interviewed by Hyperallergic. Many of the models, most of whom are artists themselves, reported feeling overlooked in the art world despite their prevalence in educational institutions.

“On Wednesday, December 17, members of the Art Students League, which currently contracts 80–90 models depending on class needs, will vote on a new board. As the institution marks its 150th year, the newly formed Art Students League Model Collective is asking incoming leadership to hear their concerns for improved labor conditions, including raising their $22/hour rate, offering more stable working hours, and providing up-to-date heaters and amenities.

“The models interviewed by Hyperallergic, some of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of losing work, also hope that sharing their stories will lead to increased respect for the profession.

“Anna Veedra, an art model who does not work for the Art Students League, is leading the push for change at the institution through her advocacy organization, The Model Tea Project. Veedra is sending a survey to art models across the country, an initiative she told Hyperallergic would ‘provide the model community with data to match their lived experience.’

“Veedra said she prefers flying to California to take jobs, including at animation studios, rather than working in New York, where institutions like Parsons and the New School pay around $20–25 an hour, according to models who work there. …

“In preliminary data shared with Hyperallergic from 41 models heavily concentrated in New York City and at the Art Students League, over half of the respondents reported being unable to save any money for retirement or emergencies.

About half of the models said they relied on public assistance programs, including food stamps and Medicaid.

“Most models surveyed by Veedra earned below $35,000 per year, including supplemental income. Some models Hyperallergic interviewed had other jobs. A few relied on bookings entirely.

“In a statement, a spokesperson for the Art Students League said the atelier-style institution was ‘committed to providing a safe and inclusive working environment for the models who devote their time and expertise to aiding the practice of life drawing in our studios.’

“ ‘Models are vital members of our community and the League’s administration regularly holds meetings where models can share feedback and voice concerns,’ the spokesperson said. The institution did not answer questions about whether it had plans to raise pay for models or confirm its hourly rate for models.

“The Art Students League was established in the 1870s in part to increase opportunities for artists to draw life models. A century and a half later, models are hoping it could set a high standard for the industry.

“One model who works at the Art Students League and spoke to Hyperallergic called the pay ‘insulting for the type of work that it is.’ Another model said he felt the institution ‘completely take[s] us for granted.’

“Robin Hoskins, an art model from Cincinnati who works at art schools across New York City as an independent contractor, said she became so ‘desperate’ that she was searching for retail jobs earlier this year. … She wishes people would appreciate the elegance and stamina required to pose for artists.

“ ‘We’re human beings, you know, and we want to be understood and appreciated for the work we’re putting in,’ Hoskins said. ‘But, most importantly, we need to be able to have a dignified wage and be able to earn a decent living, just like anyone else in any other successful profession.’ ”

More at Hyperallergic, here. No paywall. Subscriptions encouraged.