Photo: Wikipedia.

There are so many things on this beautiful planet that we’ve never given much thought — things that turn out to be important for our future. Insects, for example, fungi, seagrass.

Allyson Chiu , with Michaella Sallu contributing from Sierra Leone, has written about seagrass research for the Washington Post.

“From the deck of a small blue-and-white boat, Bashiru Bangura leaned forward and peered into the ocean, his gaze trained on a large dark patch just beneath the jade-green waves.

“ ‘It’s here! It’s here! It’s here!’ crowed a local fisherman, who led Bangura to this spot roughly 60 miles off the coast of Freetown. ‘It looks black!’

“Bangura, who works for Sierra Leone’s Environment Protection Agency, tempered his excitement. After two unsuccessful attempts to find seagrass in this group of islands, he questioned whether the shadowy blotches were meadows of the critical underwater greenery he and other researchers have spent the past several years trying to locate along the coast of West Africa.

“It was only once he was standing in the waist-high water, marveling at the tuft of scraggly hair-like strands he’d uprooted to collect as a sample, that he allowed himself to smile.

“The wet, reedy plants Bangura held in his hands were unmistakably seagrass, and the green blades stretched past the plastic 12-inch ruler he’d been using to measure specimens. His grin grew even wider.

“The dense grass swaying in the current appeared to be healthy, and the water teemed with schools of small, silvery fish, making it the best site researchers have documented in these islands since the existence of seagrass was first confirmed in Sierra Leone in 2019. …

“Seagrasses — which range from stubby sprout-like vegetation to elongated plants with flat, ribbon-like leaves — are one of the world’s most productive underwater ecosystems. The meadows are vital habitats for a variety of aquatic wildlife.

Sometimes described as ‘the lungs of the sea,’ the grasses produce large amounts of oxygen essential for fish in shallow coastal waters.

“But, long overlooked, these critical ecosystems are vanishing. In fact, researchers don’t know exactly how many exist or have been lost. One recent study estimated that since 1880, about 19 percent of the world’s surveyed seagrass meadows have disappeared — an area larger than Rhode Island — partly as a result of development and fishing.

“ ‘When you lose foundation species like seagrasses … then you lose fisheries really quickly,’ said Jessie Jarvis, a marine ecologist who, until recently, headed the World Seagrass Association. …

“But locating grasses in the world’s vast oceans is a formidable task. While some researchers are using drones and satellite imaging, in countries such as Sierra Leone, where resources are scarce, the search is painstaking and tedious.

“Without these efforts, though, seagrasses would probably be disappearing even faster.

“ ‘What we don’t know, we can’t protect,’ said Marco Vinaccia, a climate change expert with GRID-Arendal, an environmental nonprofit that helped put together West Africa’s first seagrass atlas. …

“Similar to terrestrial plants, seagrasses have roots, leaves, flowers and seeds. Seagrasses have been discovered in the waters off more than 150 countries on six continents. The meadows are estimated to cover more than 300,000 square kilometers, an area the size of Germany. Along with mangroves, kelp forests and coral reefs, these grasses play a vital role in maintaining healthy oceans, Jarvis said. But unlike those other ecosystems, she notes, the meadows can exist in a wider range of ocean environments and tend to be more resilient than most species of seaweed.

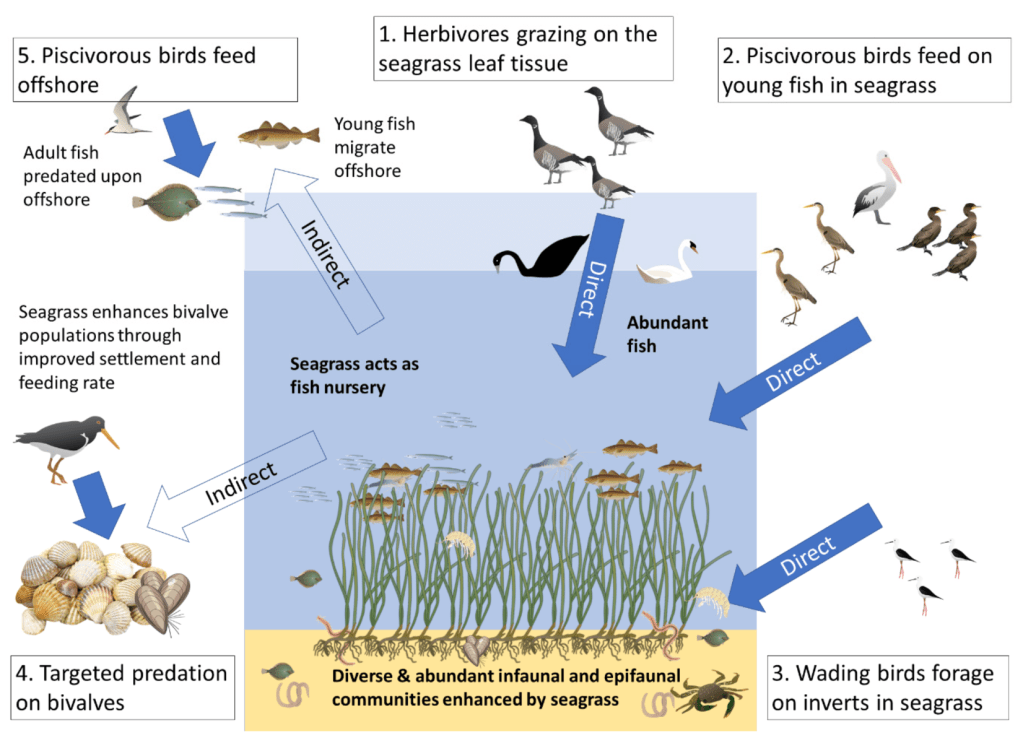

“Critters, such as sea horses, crabs and shrimp, along with juvenile fish — some of which are critical species for fishing — often lurk within the thick meadows, seeking refuge beneath the underwater canopy. Other creatures, including sponges, clams and sea anemones, can be found nestled between the blades of grass or in the murky sediment at the base of the plants. And much as mosses coat trees, many species of algae grow directly on the leaves.

“Seagrass beds can in turn attract larger animals, including turtles and manatees, that stop by to munch on the leaves and stems. …

“From the leaves down to the roots, these unassuming plants work as ‘ecosystem engineers.’ Through photosynthesis, they help fill the surrounding water with oxygen. The leaves also absorb nutrients, including those in runoff from land, while their roots stabilize sediment, which helps to reduce erosion and protect coastlines during storms.

“Seagrasses also have the potential to play a significant role in combating climate change. Just as trees pull carbon from the air, seagrasses do the same underwater. Then, as the carbon-filled parts of the plants die, they can wind up buried in the sediment on the seafloor. Over time, this can help create sizable carbon deposits that could remain for millennia.

“But the grasses aren’t showy like coral reefs or immediately recognizable like mangroves, and they’ve become one of the least protected coastal ecosystems.”

Read more about what is being done here, at the Post.