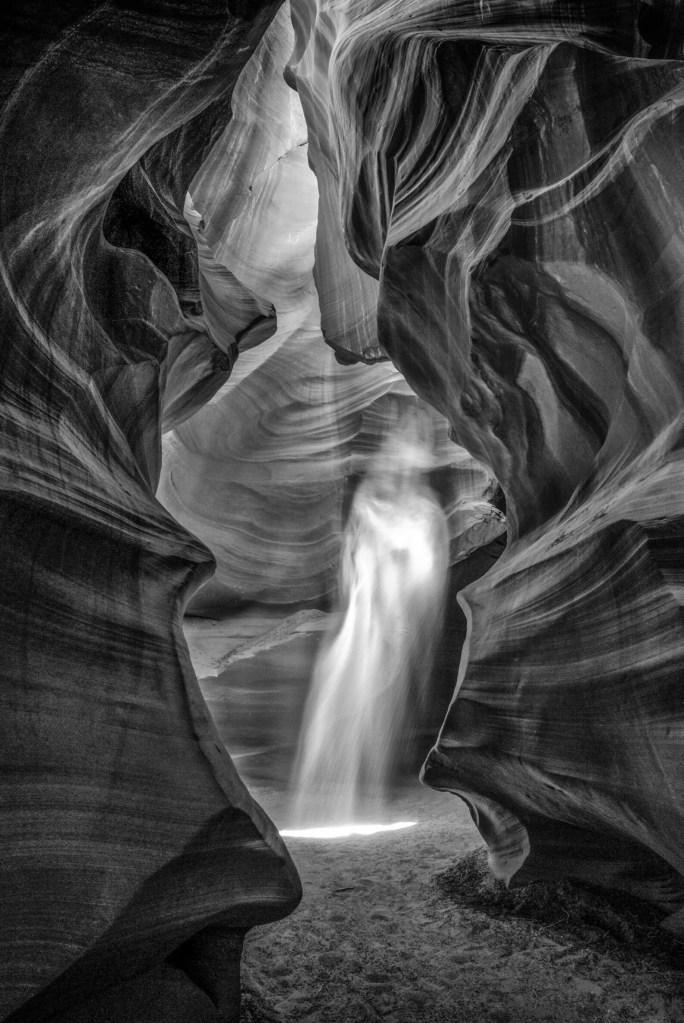

Photo: Harv Greenberg via Etsy.

How to illustrate a story on the brain’s mysterious remembering and forgetting? Do you approve of this shot of Arizona’s Antelope Canyon for the purpose?

As forgetful moments become more common for me, I tend to think of them only as bad news. This article by Sanjay Sarma and Luke Yoquinto at BBC Future asks me to look on the bright side.

“On 25 February 1988, at a performance in Worcester, Massachusetts,” they write, “Bruce Springsteen forgot the opening lines to his all-time greatest hit, ‘Born to Run.’

“According to the conventional wisdom about the nature of forgetting, set down in the decades straddling the turn of 20th Century, this simply should not have happened. Forgetting seems like the inevitable consequence of entropy: where memory formation represents a sort of order in our brains that inevitably turns to disorder. …

“In such a model, the preservation of information like song lyrics requires constant upkeep – which, in the case of ‘Born to Run,’ no one could accuse Springsteen of neglecting. … According to the entropic model of forgetting, such a slip-up made little sense. … Schools and education systems around the world had been built based on the best psychological theories of the early 20th Century. If these models of learning – and its supposed opposite number, forgetting – were wrong, who could tell how many learners had been done a disservice? …

“Efforts to explain forgetting date back to the late 1800s, when psychological researchers began – slowly, at first – to incorporate mathematical tools into their experiments. The German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus studied his own powers of recall by memorising long series of nonsense syllables, then recording how well he remembered them as time elapsed. His ability to summon up this meaningless information, he discovered, sloped downward over time in a curved distribution: he lost most of his hard-won syllables quickly, but a small percentage of them persisted in his memory long after his initial memorization efforts.

“These results seemed to support the intuitive idea that forgetting was the result of the simple erosion of information. But even in these early efforts, wrinkles appeared in the data suggesting that there might be more to forgetting than met the eye. Importantly, the timing of Ebbinghaus’s rehearsals wielded enormous influence over how well he remembered items, with a spaced-out practice schedule outperforming rehearsal sessions that were bunched together.

“This finding was mysterious, hinting at some unexplained requirements of the memorizing mind, but at the same time it was unsurprising. Indeed, the benefits of spacing out one’s studies were known to most students. …

“In Ebbinghaus’s time [quantitative] methods were the exception in psychological research, but a generation later, they were rapidly gaining adherents. Perhaps no psychologist was more responsible for this change than Columbia University’s number-loving psychologist Edward L. Thorndike. … His research laid the groundwork for the influential mid-century movement in psychology known as Behaviorism, which attempts to explain behaviors purely as a function of environmental conditioning, not any intervening mental processes. …

“From his observations he produced three basic laws of learning for human and non-human animals alike. These concerned how the brain ‘stamps in‘ associations (which he dubbed his Law of Effect); under what conditions learning occurs (his Law of Readiness); and how memories are maintained or forgotten: his Law of Exercise, which breaks down into sub-theories of use and disuse. …

“Thorndike’s theory of forgetting largely aligned with Ebbinghaus’s observations, except it didn’t account for the still-mysterious fact that spaced rehearsal of information seemed to steel-plate information against forgetfulness. It would take decades for cognitive scientists to come up with a model of forgetting that satisfactorily accounted for this issue. …

“In both the standardization of education and the ongoing research into learning, forgetting became something of a sideshow. Its status began to improve, however, thanks to two separate research traditions begun in the 1960s and 1970s. One operates at the level of neurons and is detectable through tiny electrodes implanted in cells, while the other operates at the level of cognitive psychology and is detectable through cleverly designed quizzes.

“At the cellular level, Eric Kandel, in a Nobel-winning series of studies, demonstrated that memories are preserved in the form of strengthened connections between neurons. Training regimes, he showed, whether conducted on intact, living, learning animals, or by electrically prodding neurons in a dish, create such beefed-up connections. And, as Ebbinghaus first observed, training (or rehearsal, or study) with extra time scheduled in between led these connections to be longer-lasting. This is a fact that holds true throughout the animal kingdom, from sea slugs to mammals. …

“At the cellular level, part of the answer may be that some of the mechanisms involved in preserving memories seem to require downtime: recharging periods, in effect, before neurons can get back to the work of strengthening their connections.

“A different, yet perhaps complementary, answer is forthcoming in the research tradition of cognitive psychology. Here, a variety of studies suggest that gaps in one’s rehearsal or study schedule are so helpful because, counterintuitively, they create the opportunity for a salutary bit of forgetting. To understanding how forgetting can be useful, it’s important to first recognize that a memory is never simply strong or weak.

Forgetting, it seemed, was less like a cliff slowly collapsing into the sea, and more like a house deep in the woods that becomes harder and harder to find.

“Rather, the ease with which you can summon up a memory (its retrieval strength) is different from how fully represented it is in your mind (its storage strength). The name of your parent, for instance, would be one example of a memory with both high storage and retrieval strength. A phone number you held in your head only momentarily a decade ago could be said to have low storage and retrieval strength. The name of someone you met a party mere minutes ago might have high retrieval but low storage strength. …

“Psychologists became aware of the distinction between storage and retrieval as early as the 1930s, when John Alexander McGeoch, a psychologist at the University of Missouri, tasked study subjects with memorizing pairs of unrelated words. For example, every time I say pencil, for instance, you say chessboard. That task became far more difficult, he discovered, when, before asking his subjects to recite what they’d memorized, he confronted them with decoy pairs: pencil and cheese, pencil and table. The decoy pairs, it seemed, competed with the true pair for the memorizer’s attention.

“As this line of research gained traction, the metaphor for forgetting changed. Forgetting, it seemed, was less like a cliff slowly collapsing into the sea, and more like a house deep in the woods that becomes harder and harder to find. The house might be perfectly sound – that is, its storage strength remains high – but if the path leading to it becomes surrounded by equally plausible paths leading the wrong way, one’s formerly clear mental map can transform into a maze.

“In Springsteen’s case, it’s easy to see how his mental wayfinding might have gotten thrown off track. ‘The reason for the muff, apparently was that he was concentrating so much on the spoken introduction, telling the audience how the song has assumed a new meaning to him over the years,’ the Los Angeles Times’ music critic wrote several days after the event. The new introduction meant he was approaching the same old memory from a different set of cues: a different starting point. Suddenly, the once-reliable path to the opening lines of the song was surrounded by false starts. But soon, the lyrics came roaring back.” The idea is that now the memory is more accessible and the heightened accessibility will stick around.

Pretty cool stuff. More at the BBC, here. No firewall.