Illustration: Elara Tanguy.

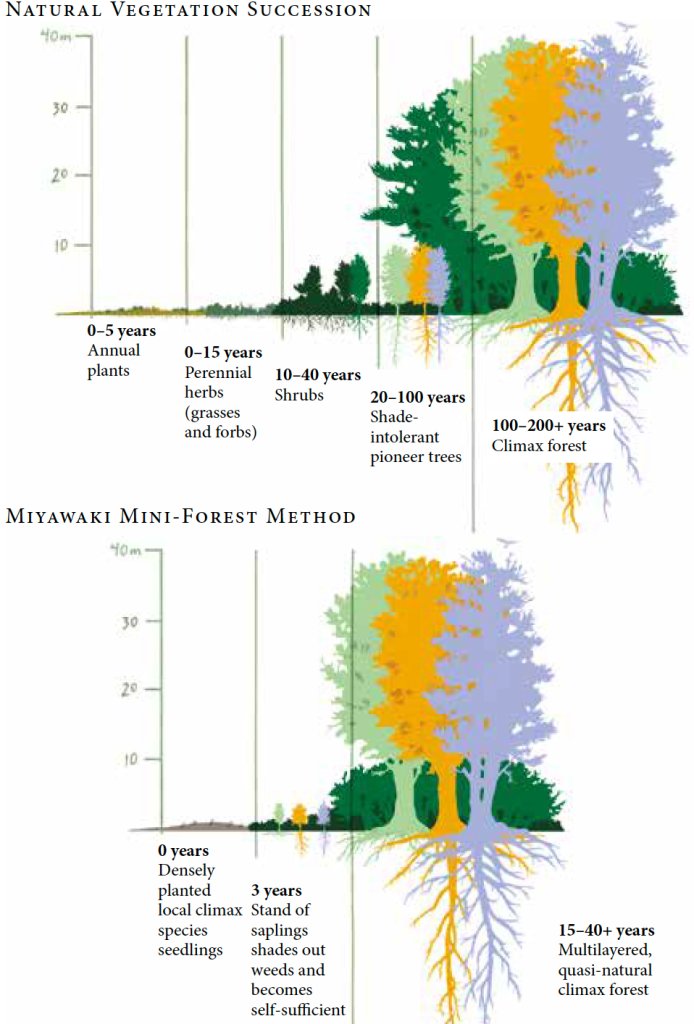

The Miyawaki Method (bottom) speeds up the process of natural ecological succession (top) through the planting of “climax species.”

Ideas on combating climate change through the planting of sustainable forests come today from an employee-owned publishing company called Chelsea Green. Here they focus on a book by Hannah Lewis about the Miyawaki Method.

“Author Hannah Lewis is the forest maker transforming empty lots, backyards, and degraded land into mini-forests and restoring biodiversity in our cities and towns to save the planet. …

“Most of us know the term old-growth forest, which refers to natural forests that are still mostly free of human disturbance (though not necessarily free of human presence). These forests have reached maturity and beyond — a process that often takes centuries. As a result, they host incredible biodiversity and sustain a complex array of ecosystem functions.

“The Miyawaki Method is unique in that it re-creates the conditions for a mature natural forest to arise within decades rather than centuries.

At the heart of the method is the identification of a combination of native plant species best suited to the specific conditions at any given planting site.

“As we’ll see, determining this combination of special plants is not always so straightforward.

“More than just the species selection, the Miyawaki Method depends on a small collection of core techniques to ensure the success of each planting. These include improving the site’s soil quality and planting the trees densely to mimic a mature natural forest. It’s also necessary to lightly maintain the site over the first three years — which can include weeding and watering. Amazingly, though, if the simple guidelines are followed, after that point, a Miyawaki-style forest is self-sustaining.

“The trees grow quickly (as much as 3 ft per year), survive at very high rates (upward of 90 percent), and sequester carbon more readily than single-species plantations. The Miyawaki Method is also special for its emphasis on engaging entire communities in the process of dreaming up and planting a forest. Whether you are three years old or eighty-three, chances are you can place a knee-high seedling into a small hole in the ground. At the very least you can appreciate and cherish the return of quasi-wilderness to a space that was once vacant.

“The Miyawaki Method calls for planting native species, but not just any natives. In particular, the method involves a careful investigation of what’s known as potential natural vegetation (PNV). This unusual term refers to the hypothetical ecological potential of a piece of land. Or another way to say it is that potential natural vegetation is ‘the kind of natural vegetation that could become established if human impacts were completely removed from a site’ over an extended period of time. A site’s PNV depends on many factors, including current climate conditions, soil, and topography.

“How is potential natural vegetation different from the plants we see growing around us in towns and cities? For starters, in almost all developed landscapes, many of the plants are not native to the area, and as such may require maintenance to survive or reproduce.

“Given that most of Earth’s land surface is significantly altered by urbanization, agriculture, road construction, mining, and the like, it is far from obvious what the original vegetation of any given location would have been. (Original vegetation and potential natural vegetation are not necessarily exactly the same, but they are closely related.) Unraveling this mystery takes curiosity, patience, and persistence.

“However, thinking about land in terms of its potential natural vegetation is a powerful angle from which to approach ecosystem restoration, because it reveals which species and groups of species are best adapted to a particular environment and therefore more likely to thrive and to support a wider web of wildlife. …

“If left alone, previously forested land can grow back into mature forest via a process known as ecological succession, wherein the biological components of the ecosystem change over time as larger and longer-lived plant communities colonize the land. As mentioned, this process can take centuries to unfold. A foundational aspect of the Miyawaki Method is that it sidesteps the slow and capricious march of natural succession, instead focusing on those plants that mark the theoretical endpoint of succession.

“In nature, the successional process begins when lightweight seeds drift in and germinate on bare ground. Hardy, fast-growing plants — what scientists call pioneer species — such as clover, plantain, and dandelion take advantage of ample sunlight and space. They live short lives, produce a lot of seeds, and shelter the ground in the process. Next to show up are larger perennial herbs and grasses, followed by shrubs and pioneer trees, such as birch, poplar, or pine.

“ ‘Each new group of species arrives because the environmental conditions, especially the soil, have been improved; each new species becomes established because it is more shade tolerant than the previous species and can grow up under their existing foliage,’ Miyawaki wrote. He explains that just when a community of plants appears to be reaching its fullest potential, the seeds of the succeeding community are already germinating in its shade. The species making up each new successional stage tend to be bigger, more shade-tolerant, and longer living than those of the previous stage.

“ ‘The plant community and the physical environment continue to interact,’ Miyawaki explained, ‘until the final community most appropriate for the environment comes into being, one that cannot be replaced by other plant types. In regions with sufficient precipitation and soil, the final community is a forest.’

“Theoretically, this final community of plants, known as the climax community, is not easily superseded. Big trees that are considered climax species in their respective environments live for hundreds or thousands of years, forming canopies that shade the interior of the forest, keeping it cool and moist. Climax species shade out pioneer species and dominate the forest.

“ ‘In the absence of major environmental change, the climax is normally the strongest form of biological society and is stable in the sense that its dynamic changes are constrained within limits,’ Miyawaki wrote. Partly on account of the microclimate they create, such ecosystems tend to be more resistant to external conditions, such as heat or drought.”

More at Chelsea Green, here. No firewall.