Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Descendants of potter David Drake, seen at the Museum of Fine Arts with one of the artist’s works.

If we are in a hurry for the many evils we see to be defeated, we’re likely be disappointed. But in time, even a foundering ship can right itself. The growth of initiatives to return artifacts stolen in the past is an example.

Jori Finkel writes at CNN that in a “likely precedent-setting agreement, the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston has agreed to return two works from 1857 by the Black potter David Drake, who made his ambitious jars while enslaved, to his present-day descendants.

“By the terms of the contract, one of those vessels will remain on loan to the museum for at least two years, according to the lawyer George Fatheree, who is representing Drake’s descendants. The other vessel — a masterpiece known as the ‘Poem Jar’ — has been purchased back by the museum from the heirs for an undisclosed sum. Now the work comes with ‘a certificate of ethical ownership.’

“ ‘In achieving this resolution, the MFA recognizes that Drake was deprived of his creations involuntarily and without compensation,’ a museum spokesperson said in a statement. ‘This marks the first time that the museum has resolved an ownership claim for works of art that were wrongfully taken under the conditions of slavery in the 19th-century US.’ …

‘Ethan Lasser, chair of the art of Americas at the MFA, said the museum has learned from its work restituting Nazi-looted art. ‘We’ve become very expert in Holocaust restitution. We’re dealing with (repatriation) issues in our African collections and Native American collections,’ he said over the phone. …

“He considers Drake’s work an example of ‘stolen property,’ too, ‘since the artist is always the first owner of his work and he never got to make the call about where it went or what he was paid for it.’

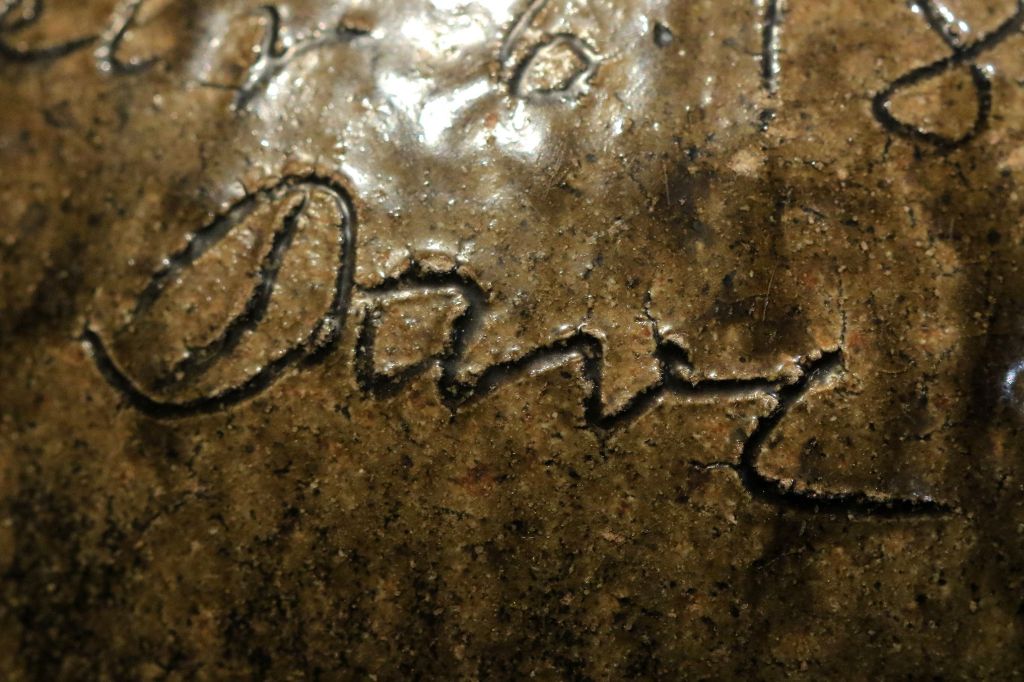

“Born enslaved around 1800 in Edgefield, South Carolina, a region known for its rich clay, Drake (who was also known as Dave the Potter) was one of relatively few African American potters to sign his work. He also dared — despite punitive anti-literacy laws for enslaved people in the state — to etch short sayings or poems on the jars, making them powerful acts of resistance. Some inscriptions boast of the jar’s intended contents or enormous capacity; others remark more poignantly on his own life or working conditions.

“The ‘Poem Jar,’ which the MFA originally bought in 1997 from a dealer in South Carolina, features a couplet that hints at Drake’s financial exploitation. The inscription reads: ‘I made this Jar = for cash/Though its called Lucre trash.’ Currently in a gallery for self-taught and outsider art at the museum, it will assume a more prominent spot at the entrance of the Art of Americas wing once renovated in June 2026. …

“Another jar made the same year, 1857, has a particularly wrenching inscription in light of Drake’s forced separation from a woman believed to be his wife and her two sons. That vessel, at the Greenville County Museum of Art in South Carolina, reads: ‘I wonder where is all my relation.’

“One of Drake’s great-great-great-great grandsons, the children’s book author and producer Yaba Baker, said he feels the restitution process offers one answer to that question. ‘It’s been exciting, overwhelming and feels full circle,’ he said in a video call. He praised the MFA for ‘showing integrity and leadership’ in ‘allowing us to connect to Dave’s legacy,’ noting that ‘to go from being slaves to having a family of engineers and doctors and people in executive positions is a testament to Dave’s legacy in a different way.’

‘These descendants began talking about getting involved in Drake’s legacy in 2022, upon the opening of ‘Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,’ an exhibition jointly organized by the MFA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The family soon hired Fatheree, fresh from his win in the Bruce’s Beach land reparation case. Earlier this year they established the David Drake Legacy Trust, governed by five of the oldest heirs.

“So far there are about 15 family members involved, according to Fatheree, but they have created a website so that other descendants of Drake can be identified and join the efforts — what Fatheree calls ‘a big tent approach.’ …

“There are thought to be around 250 pots by Drake still in existence, and over the past five years the market for his work has exploded, driven mainly by American museums competing for pieces in the hopes of telling a more complex story about the history of slavery in the US. Several have paid six figures for his work, and in 2021 the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas paid a record-setting $1.56 million for a 25-gallon stoneware jar at auction.

“Other museums that own Drake’s work include the Met, the Philadelphia Art Museum, the De Young Museum in San Francisco, the Art Institute of Chicago, Harvard Art Museums, the St Louis Art Museum and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, as well as smaller venues in the American South.

“Fatheree confirmed he has begun to reach out to some of these other art institutions on behalf of the family. ‘Our approach has been one of collaboration and invitation. I am not a litigator; we did not go to the museum and file a lawsuit (or) threaten to sue them. But our hope and frankly our expectation is that other institutions’ — and private collectors of Drake’s work, he added — ‘will follow the Boston museum’s lead here.’ ”

More at CNN, here.