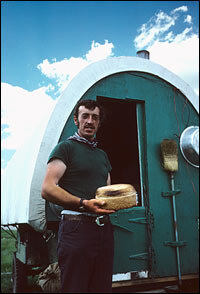

Photo: John Burcham.

Textile weaver and fiber artist Roy Kady.

Today’s story is about a man for whom work and art are inseparable: Navajo weaver Roy Kady.

Elaine Velie at Hyperallergic conducted the interview.

“Diné weaver and fiber artist Roy Kady sat down for a video interview wearing a shirt that read ‘Sheep is life.’ Kady is a shepherd and an artist, roles he sees as definitively intertwined. ‘I am first a shepherd, then art comes with it,’ he said.

“Kady’s decades-long career has been one of constant learning, and in recent years, teaching. He shares weaving techniques and Diné stories that he says are too often missing from younger generations. Kady spoke to Hyperallergic about Diné conceptions of gender, apprenticeship in his small Arizona town, and being accepted as a gay man in his community.

“Hyperallergic: What are your earliest memories of weaving, and how did your mother’s practice influence your own?

“Roy Kady: My sisters and I grew up in a single-parent household where my mother brought us up, so we were taught everything from building a house to repairing a roof to working under the hood of a vehicle, the sort of things the colonized world would call ‘man’s work.’ We learned inside, too. From washing dishes and getting the house tidied up to cooking and baking, we did what would be considered ‘women’s work.’ But for us, it’s not.

“I was taught about weaving at the young age of nine years old. I have some recollections before that of sitting by my grandmother, grandfather, and mother, who all also partook in fiber arts — weaving and processing the fiber. My mom gifted and shared weaving techniques with me: vegetable dyeing and some of the family designs that came with it. I was fortunate; I was given the tools she and our kin relations had, and that’s what inspired me to become an artist. We learned farming and goat and sheep herding, too. …

“Sheep provide you with sustainability, food, and the opportunity to learn how to maintain the land. We take care of them so that they can take care of us.

“As a shepherd, you know what they like to eat and what keeps them healthy. They also know that themselves, so they’ll take you on journeys to where particular plants exist. On those journeys, you’re able to be inspired by color and the environment, by the mesas. You start to see geometric forms that you can bring back to your weaving repertoire.

“That’s what traditional Navajo weaving is: an interpretation of your environment. A lot of my earlier pieces were designed with that in mind. They’re not necessarily just stripes; they represent rainbows. They’re not just step patterns; they’re mesas or clouds.

“There’s a whole opening of the universe that is represented. In order to understand and have that knowledge, you must have the knowledge of shepherding. But it’s a rarity now because there are not many shepherds. The sheep population has really declined. Navajo fiber artists and textile weavers create beautiful artistry, and while they may no longer have herds, they have memories from their grandparents or parents or maybe from within themselves around growing up with sheep. …

“My mother would sometimes say something like, ‘You’re at the age when you are going to learn about horsemanship.’ She was a horsewoman type. She would teach us, then she would want us to ask a neighbor or other kinfolks to learn other forms. I remember growing up and learning a lot from the neighboring kids. We would go to their houses and learn different types of fiber arts, traditional recipes, or plant foraging. …

“I would go spend a day, a weekend, or even a month in their home and helping them with their livestock. That’s how I would earn the opportunity to learn from them. They’ve always told me that this knowledge doesn’t just belong to one individual, saying, ‘It was gifted to me. It goes all the way back to the creation story.’ That’s how I model my apprenticeships now. …

“I don’t just use wool. I use anything that’s of natural origin, including tree bark and wild cotton, nettle, silk, you name it — whatever I can get my hands on. If I can find somebody who says, ‘I have a herd of bison,’ then I say, ‘What do you do with their wool?’

“H: Are there any works that you particularly love?

“RK: That would be the one titled ‘Shimá,’ meaning ‘my mother.’ I would wheel her into the sheep corral in her wheelchair, and the sheep knew who she was and come up and greet her. They knew the scent of her hands and how she cared for them. I took a beautiful picture of her making those interactions and decided to weave it. I broke ground for myself by incorporating all different types of techniques that I’ve learned along my weaving journey. At this point, that would be my favorite. …

“H: Are there any projects you’re working on now or that you’re excited to start in the future?

“RK: There’s an upcoming gallery exhibit near us in Cortez, Colorado, that I’m starting with my grandson, Tyrell Tapaha. He’s come back to learn about shepherding and be my apprentice. We’re doing a collaborative type of show. I will show what took place between the two of us, and it will include his interpretation of what I taught him about sheep, the landscape, or a particular plant.

“We are utilizing what we call barbed wire art. When you’re a sheepherder in this country, you have barbed wires lying around everywhere that are rusty, but we create these wonderful shapes and incorporate that into our textiles or fiber work. We’re excited to venture.”

Read more and see how the artist wove an image of a sheep at Hyperallergic, here. No firewall. Subscriptions encouraged.