Photo: Lakshmi Rivera Amin/Hyperallergic.

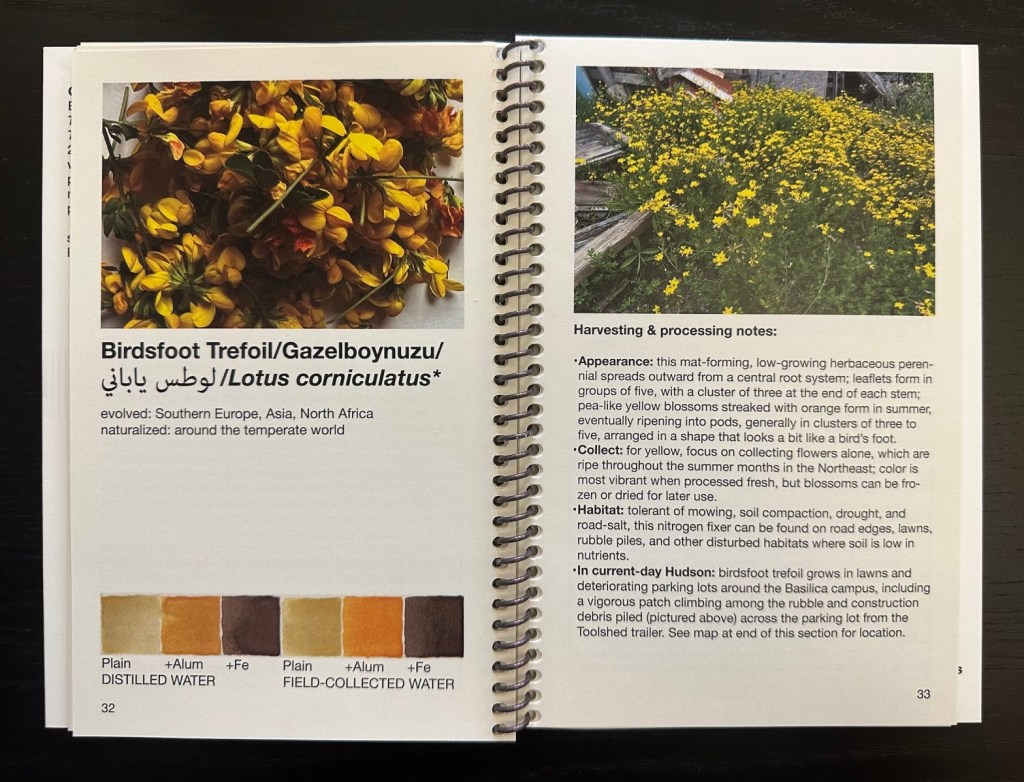

Page spread from Feral Hues, a book by Ellie Irons on making your own paints.

Artistic types are going back to nature for pigments these days. My friend Ann grows special weeds and flowers to make dyes for her beautiful textiles. In today’s Hyperallergic interview by Lakshmi Rivera Amin, we learn about an artist making her own paints.

“Taking the concept of a ‘green thumb’ several steps further, artist Ellie Irons approaches plants as a literal source of color: She creates her watery paintings with pigments tinted by organic hues found in the natural world. These works … record, honor, and reorient our relationship to the vegetation around us, specifically in current-day New York State’s Hudson area.

“I picked Irons’s brain about the process of creating her own paints through harvesting on the occasion of her recent book, Feral Hues: A guide to painting with weeds (Publication Studio Hudson). This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

“Hyperallergic: What is the most joyful part of making your own pigments?

“Ellie Irons: There are many joys, which is why I’ve been entranced by the process for so many years: an ever-deepening and shifting connection to urban ecosystems and the land that supports them that emerges through careful, considered harvesting practices; the smells, colors, and textures that reveal themselves when plant parts are processed by hand in the studio; the joy of sharing the process with other humans who also become entranced by the relatively simple act of lovingly harvesting often overlooked weedy plants and creating paint with them; the process of attuning to the cycles of vegetal life sprouting, growing, blossoming, fruiting, [dying] across the seasons and years — there is always something to delight in and harvest, in any habitat, even in deep winter. …

“H: How has your practice evolved over the past several years?

“Irons: I would say recently, since maybe 2019, my work has become more locally rooted and grounded. In the decade before that, I found myself investigating plants across urban habitats in a global sense — comparing pokeweed and honeysuckle growing in a parking lot in Taipei with the same species sprouting from a concrete river in current-day Los Angeles, for example.

“I’m still fascinated by those global connections, and find them resonant and relevant, but in recent years my focus and my daily practice have shifted to be more bioregional — I take the Mahicanituck/Hudson River Watershed as a salient range in which to work, connecting with human and plant populations up and down the river from New York City to the Adirondacks. …

“This shifting focus is based on a range of factors, from my increasing discomfort with energy-intensive travel to my new(ish) status as a mother to my day job with a community science and art organization that focuses on hyper-local environmental justice issues, to of course, the ongoing impacts of the pandemic. There are other ways it has changed, of course — writing has become increasingly important to me, as has enduring land-based work (a result of living in a shrinking upstate city where access to soil and open earth is simpler than in New York City, where I started working with plants more than a decade ago).

“H: What are your favorite plants to work and be in relation with, and why?

“Irons: Perhaps unsurprisingly, I have many favorites, and feel fortunate regularly meet plants who are new to me — my loves change by the season, and across contexts. Right now, in early August, each morning I’m greeted by innumerable, intensely blue Asiatic dayflower … blossoms lining the border of my neighbors’ chainlink fence where it meets the sidewalk.

“The blossoms only last until noon or so, depending on the weather and the intensity of the sun. I take 20 to 30 blossoms most mornings, and store them in a small cup in the freezer, accumulating them until I’m ready to process them into a range of shades of blue.

“I love dayflowers for the way they become unmissable once they catch your eye, and draw you in. They have an unassuming stature, foliage that’s easy to overlook, but when they burst into flower for several hours each morning, the proliferation of electric blue petals — almost sparkling if you look closely — can feel like tiny jewels sprinkled along the sidewalk. …

“Having migrated to the American continent, they live well in cities, where they are sometimes appreciated as a ‘wildflower,’ and are gaining notoriety as a super weed in round-up ready soybean fields, where they’ve demonstrated resistance to the herbicide glyphosate. And in their native China they are being studied as a hyperaccumulator due to their ability to thrive on the polluted soils of old copper mines, absorbing large amounts of heavy metals. …

“H: What do you hope anyone interested in approaching plants as material sources for art will first consider and reflect upon?

“Irons: I hope people will keep in mind processes of gratitude and respect — of mutual exchange, rather than of taking to satisfy a material need. This can look many ways. Maybe even just asking yourself a few questions before harvesting: Who else might be in relation with this plant, human or more-than-human? What is the plant doing here and why? How long has this plant been here, will they be here tomorrow, or in 100 years?”

More at Hyperallergic, here. No paywall, but subscriptions are encouraged.

Photo: Ermell/Wikimedia Commons.

Asiatic Dayflower, or Commelina communis.