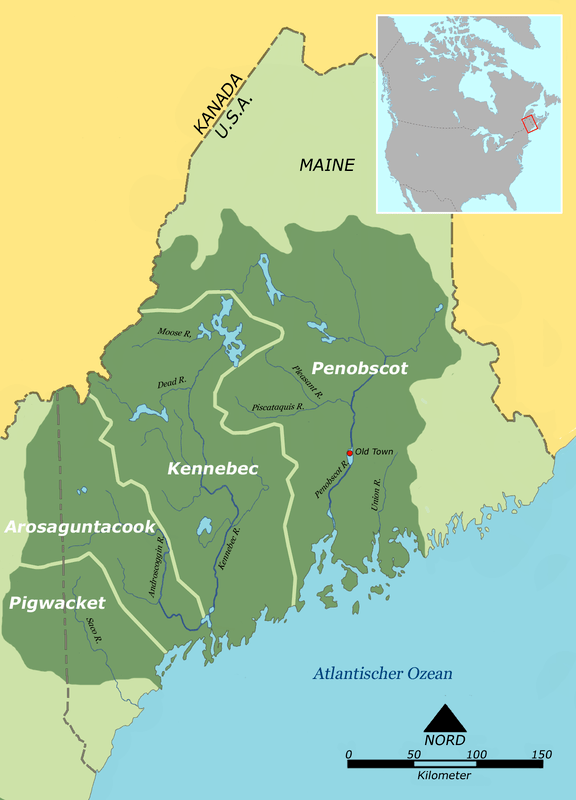

Map: Wikipedia.

Eastern Abenaki tribes (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket). Indigenous people often exhibit the best stewardship of natural resources.

What can we learn from people who have been taught from infancy how to live in harmony with the natural world? In an op-ed at the Washington Post, Bina Venkataraman suggests that “in Maine, a return of tribal land shows how conservation can succeed. …

“On a recent morning at the Penobscot Nation headquarters, moose mating rituals dominated the office banter: the wacky way a lovesick moose had stumbled around someone’s pickup truck [when] he heard a hunter’s [mating call]. …

“The Penobscot Nation’s record of caring for nature while still using it — hunting moose and duck while keeping their populations steady, selectively harvesting timber to preserve forests and restoring rivers to support fisheries — inspired an effort to return a 31,000-acre tract of forested land to tribal ownership.

“Late last year, the Trust for Public Land, a conservation group, bought the parcel from an industrial timber company, and today it announced it will give the land to the tribe once it pays off $32 million in loans. …

“The land is close to Mount Katahdin, sacred in Penobscot tradition, and to an 87,000-acre national monument created in 2016 in the North Woods of Maine. It contains 53 miles of streams in the watershed of the Penobscot River, which has been for the tribe a central highway and a source of food and water.

“The transfer is part of a movement to return lands to Indigenous stewardship and work with tribal communities to protect biodiversity. The hope is both to restore justice for tribes that were long ago stripped of their ancestral homelands and to learn from long-standing Indigenous practices new ways to save a beleaguered planet. The pending land return in Maine, or ‘rematriation’ as some Indigenous people call it, stands out because of its scale — many previous land returns in the eastern United States have been on the order of hundreds of acres — and because the Penobscot will decide how the land will be managed.

“This is a significant change. For most of the past two centuries, Western conservationists have largely ignored Indigenous people’s knowledge of landscapes and wildlife, along with tribes’ historic claims to the land. But that is no longer tenable. Worldwide, Indigenous-managed lands host 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity, by some estimates, and encompass much of the world’s remaining intact forests, savannas and marshes. If environmentalists and political leaders hope to conserve more natural landscapes … collaboration with tribal nation leaders is critical.

Modern environmentalism has been deprived of Indigenous knowledge, in part, because it has seen nature as something apart from humans.

“Early thinkers hold some responsibility for this. John Muir, long lauded as the father of the national parks, believed that natural landscapes needed to be stripped of the Native Americans who lived on them to create his ideal of pristine wilderness. In the Muir tradition, the U.S. government drove tribal people out of areas that today are considered America’s most beloved landscapes — Yellowstone, Yosemite, the Everglades — a history documented by David Treuer, an Ojibwe writer.

“The federal government created the National Bison Range in 1908 by evicting tribal members from more than 18,000 acres of the Flathead Indian Reservation — ignoring century-old practices for keeping up the bison herd. Only recently has the government returned the land to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, whose successful traditional methods for maintaining the herd are featured in a forthcoming ABC documentary.

“When Henry David Thoreau … traveled to the Maine woods in the 19th century, he distinguished between ‘scientific men’ and Indian guides, even as he acknowledged the latter’s navigational expertise. It’s laughable now to think that communities that had inhabited a place for centuries, gaining intimate knowledge of the natural features, flora and fauna and passing down that knowledge across generations, could have less to offer scientifically than settlers encountering those lands for the first time. Yet it was only last year that the U.S. government formally recognized how much tribes can contribute to ecological knowledge of their ancestors’ landscapes. …

“For decades, tribal members in Maine advocated bringing down Penobscot River dams that once powered saw and paper mills to restore an Atlantic salmon fishery. The Penobscot method of timber harvesting, which leaves 75- to 100-foot buffers of trees around rivers and streams, creates ideal conditions for salmon. Salmon like to spawn upriver in shady pools, created by allowing the forest at a river’s edge to thicken and birch trees to fall into it. …

“Some evidence suggests that, globally, the track record for Indigenous management of wildlife is at least as good as that of formal conservation. Researchers have shown, for instance, that Indigenous-managed lands in Canada, Australia and Brazil contain biodiversity equivalent to that of areas designated for conservation.

“But perfect alignment between tribes and environmental groups doesn’t always happen. The economic challenges that many tribes face — and their efforts to acquire land to reclaim sovereignty — often force tough decisions about development, gambling and heavy industry. Some tribal nations have greenlighted oil and gas drilling. The Penobscot have allied with conservationists to oppose a proposed zinc mine in northern Maine because of its likely harm to fisheries. But several tribal members expressed to me their misgivings about wind farms, which most environmentalists see as essential to combat climate change.

“Penobscot leaders have varying visions about how they might one day develop the land that is now being returned to them. Some imagine using it to adapt to sea-level rise — by building housing or growing food; others envision ecotourism lodges or a cultural center that could be accessed by the general public. In the near term, tribal leaders aim to make it accessible to hikers and hunters with permits and to offer public access to the national monument via an old logging road.

“In other parts of North America, co-management of conservation areas is becoming more common. … Groups such as the Trust for Public Land and the Nature Conservancy are brokering more land returns and collaborating with tribes to manage ecologically important landscapes. But more private landowners, philanthropists, nonprofit groups and governments should mimic the efforts in Maine. …

“Environmental movements might have better protected nature if they had long sought to conserve cultures and communities along with land. Earning the trust now of people who have inherited wisdom for living in balance with nature will give conservation a fighting chance on a warming planet.”

More at the Post, here.

This is welcome news! Thanks for sharing it. I especially like the ways salmon will be protected.

These handovers sometimes sound simple, like throwing a switch. But when the Penobscot Nation carried the day on dam removal a few years ago, I remember reading how long and complicated the negotiations were, how many parties were involved, and how difficult it was to get to Yes.