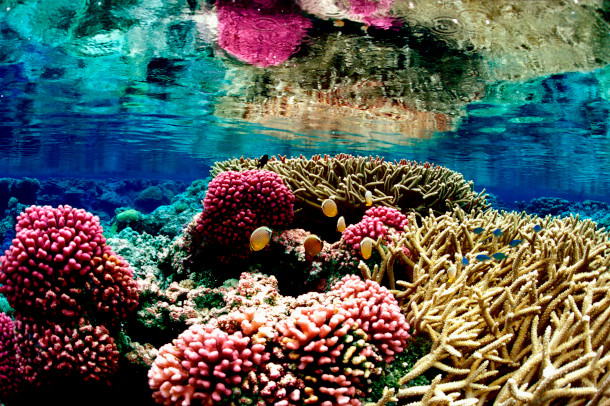

Photo: Thor Pedersen.

Thor Pedersen took a container ship from Praia, Cape Verde, to Guinea Bissau — one step in his quest to travel the world without flying.

I recently met a couple who are unusually thoughtful about their footprint on Planet Earth, to the point of investigating how they could get to Europe without flying. There are ways to travel without flying, as we learn from today’s story in the Guardian, but they all have a cost in carbon emissions — ocean-going vessels especially. Unless you’re talking sailboats, which are not practical for most people.

Nevertheless, experiments in avoiding airplanes are consciousness raising — and often fun. Thor Pedersen reported on his own effort to travel everywhere without flying. It took him 10 years!

He writes, “Growing up, it seemed as if all the great adventures had happened before I was born. But in 2013 I discovered that – although it had been attempted – no one had made an unbroken journey through every country without flying. I had a shot at becoming the first to do it. …

“At 34, I set off – and didn’t return home until almost a decade later. These are the lessons I learned along the way.

“1. Human generosity can be astounding. It was a cold, dark night in December. A train had brought me to Suwałki, which people say is the coldest city in Poland. It was quiet. Snow was falling, but otherwise everything was still. I was carrying a piece of paper with a name, a phone number and an address for where I was supposed to be staying. But I had no sim card, so I began walking, looking for someone who could help me.

“Just as I was beginning to wonder if I would ever meet anyone, a woman opened her front door. I dashed over. Luckily, she spoke English and invited me in. She was happy to host me and convinced me there was no point in heading back out into the cold.

“I was quickly given a full plate of food and a spare bed. All this from a stranger. The next day, I was served breakfast and taken to the bus that would carry me to Lithuania.

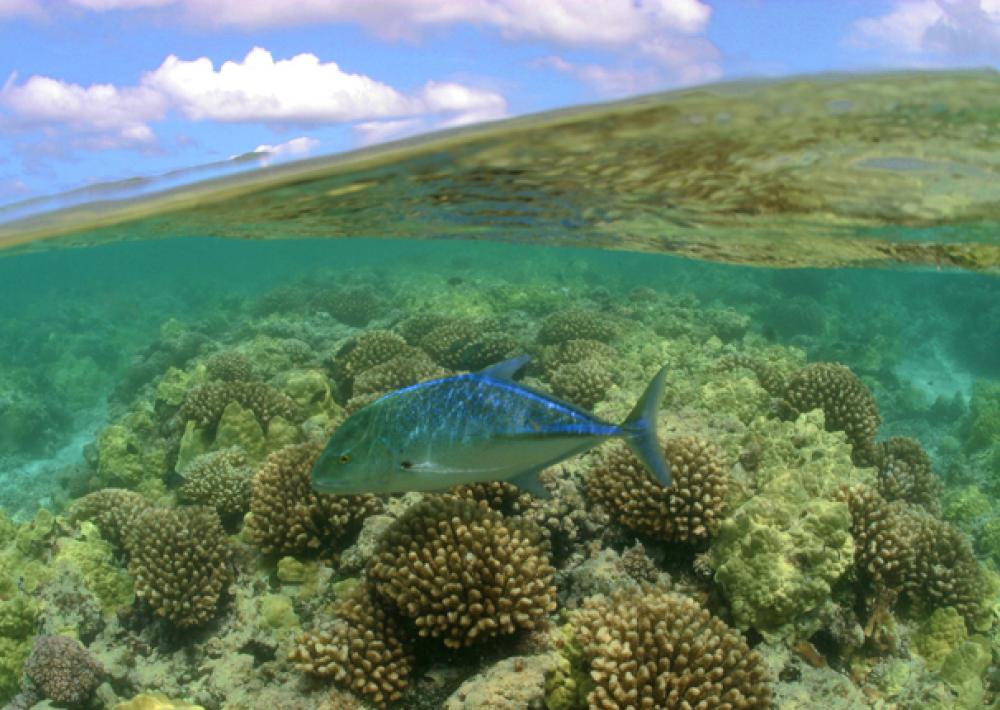

“2. There are still some hidden and spectacular natural wonders. Lesotho was country No 106 on my very long journey. Its natural beauty was immediately apparent. … The mountains of Lesotho are horse country. Every now and again, riders draped in thick blankets would pass. Then I reached Maletsunyane Falls. The nearly 200-metre waterfall was glistening in the sun at the end of a canyon. And I had it all to myself.

“3. People’s resilience is powerful. In 2015, I travelled through western Africa. At the time, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia were dealing with the world’s largest Ebola outbreak. A taxi driver in Guinea said to me: ‘Here we have everything, but we have nothing.’ These countries are rich in many ways – from natural resources to beautiful landscapes – yet most of the people are not.

“But after only an hour in Sierra Leone, I had been invited to a wedding: loads of music, lots of people in fancy clothes, an abundance of food and drink, small talk and dancing. …

“4. Isolating yourself is a mistake. When you take public transport in Denmark, where I’m from, you always pick the seat farthest from everyone else. We value our privacy and respect the privacy of others. But in much of the world, the best seats are the ones next to other passengers. Where else will you find conversation?

“In west and central Africa, I found that everyone in a bus or a bush taxi would immediately form a unit, sharing food and stories and holding babies for one another. …

“5. What you want and what you need are not the same thing. … I hit a wall after about two years, but had to push through it to reach my goal. I learned the difference between what I want and what I need. I learned to live on a rock and how to engage in conversation with absolutely anyone. Once I returned home, I realized the only things that had kept their value were the relationships and conversations I had had. Everything else seemed perishable.

“6. You can form connections without sharing a language. I once had a 12-hour train journey from Belarus to Moscow during which no one else spoke anything but Russian. It didn’t seem to bother them that I didn’t know the language beyond nyet or da; they sat and spoke to me in Russian for several hours, while we shared food and vodka.”

To see more of Pedersen’s photos and his life lessons from this kind of travel, click at the Guardian, here. No paywall.