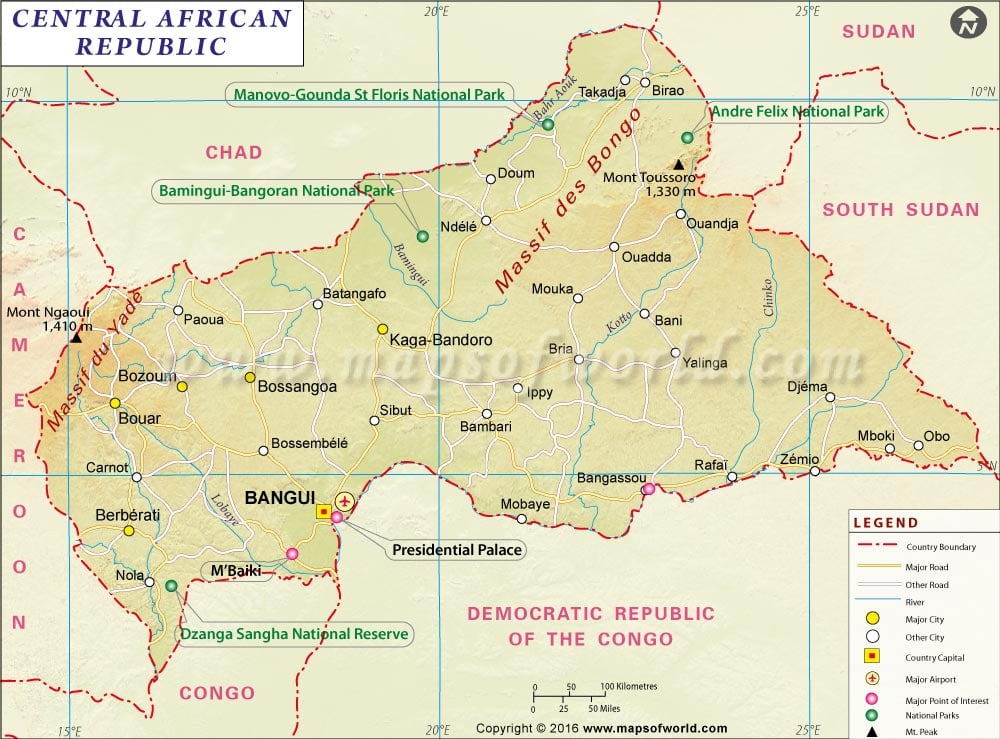

Map: Maps of the World.

The National Ballet in the Central African Republic brings to life traditional dance forms from different ethnic groups across the country.

In parts of Africa where colonialism glommed together disparate tribes with ancestral enmities, wars have continued off and on for decades. But the Central African Republic (CAR) is setting a different example, with the help of its national ballet company. The idea is to give all the CAR groups a moment in the sun by highlighting the dance traditions of each. The effort also brings people together in new ways.

In the following article, we learn about a number of ethnic dance groups, including the National Artistic Ensemble that performed recently at the Africa Day of School Feeding (ADSF) in Bouboui. [See the African Union site for an explanation of ADSF. Interesting.]

France24 reports: “The dancers shake their hips, kicking their feet to the beat of the age-old ‘dance of the caterpillars,’ typically performed in the south where the insects are gathered for food.

“Three times a week the National Ballet rehearses traditional dances of the many ethnic groups making up the Central African Republic.

” ‘The creations they ask of us are based on the particularities of each ethnicity. I’m Banda and I have to suggest dance steps from the Banda ethnic group,’ Sidoane Kolema, 43, said.

“They aim to preserve the heritage of the CAR, a mosaic of ethnic groups that is scarred by decades of conflict and instability and is among the world’s poorest countries.

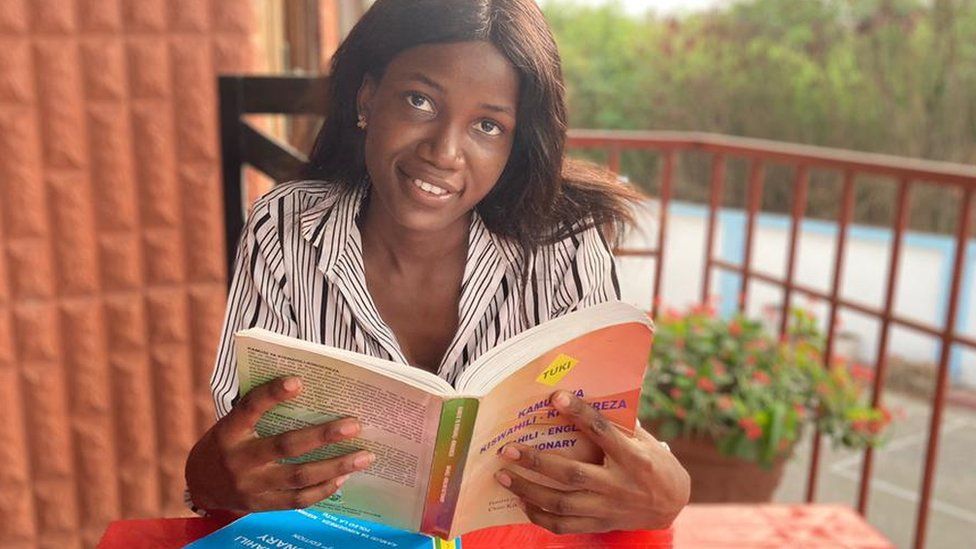

“From behind the scenes, 26-year-old Intelligentsia Oualou began singing in Gbanu, the language of her native southwestern Ombella-M’poko region.

“To the jingle of bells and rhythmic thud of the drum and xylophone-like balafon, the spinning silhouettes of the other dancers soon appeared across the dilapidated stage, set up on waste ground in the capital Bangui.

” ‘All my relatives are artists and I’ve dreamed of being an artist too,’ said Oualou. She is one of 62 dancers in the National Artistic Ensemble, created by CAR President Faustin Archange Touadera in 2021.

” ‘Promoting our cultures means going to the hinterlands to find the different dance steps of the Central African Republic in order to create a show that is diverse,’ National Ballet choreographer Ludovic Mboumolomako, 55, said. He spent three weeks living among the Pygmies in their ancestral forests in the south in order to enrich his choreography with their dances, songs and ways of living. …

“The company is often called upon to perform the ancestral dances in public at political gatherings, inaugurations and official ceremonies. In front of officials or at festivals, they dance in costumes of raffia skirts topped with pearl belts and patterned wax-print fabrics.

” ‘We need to raise awareness among young people … by dancing the different dances of our different ethnic groups in front of everyone. Tomorrow, if we are no longer here, it will be up to them to take over,’ Kolema said.

“The dancers were even recently integrated into the civil service, just like the actors and musicians who also belong to the National Artistic Ensemble.

“One of the upsides is that the dancers ‘have not a subsidy, but a salary’ [Culture Minister Ngola Ramadan] said. …

“Kevin Bemon, 44, said he had been able to put his former ‘difficult’ life dancing at neighborhood wakes behind him, thanks to the monthly salary of [$124] – just over twice the minimum wage in the CAR. …

“For a decade until 2013, the CAR was wracked by civil wars and intercommunal conflict, and although the violence has lost intensity since 2018, tensions persist.

” ‘Traditional dance has brought us together. After the recent wars, different ethnic groups were divided. Thanks to dance, we’ve become children of the same family,’ Oualou said.”

Check out the great photos at France 24, here. No paywall.