Art: Yun-Fei Ji via James Cohan Gallery.

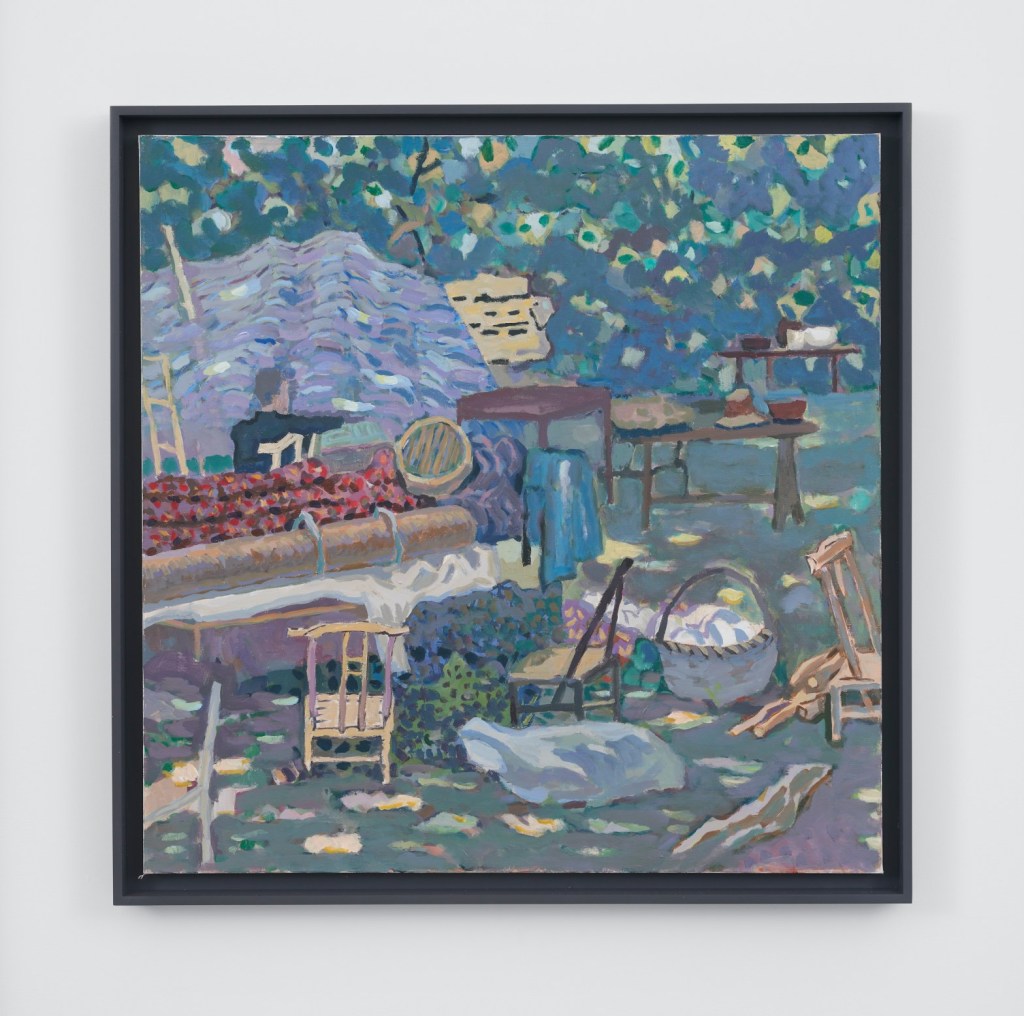

Yun-Fei Ji, “Everything Moved Outside” (2022), acrylic on canvas.

The daughter of my mother’s college friend visited us in about 1980. Her family had been deeply traumatized by the anti-intellectual fervor of the Cultural Revolution in China. She couldn’t speak much English at the time, but I understood constant repetitions of “very painful, very painful.”

When I read today’s article about an artist who evolved from the Socialist Realism he was taught at the time, I thought of Ching and the way she grew, never completely shedding the deep hurt of totalitarian madness turned against friends and neighbors.

John Yau writes at Hyperallergic about Yun-Fei Ji, a Chinese painter who learned the state-sanctioned style of Socialist Realism “and then elected to unlearn it in order to reinvent himself.

“Yun-Fei Ji was born in Beijing in 1963, three years before the start of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). Launched by the demagogue Mao Zedong, who distrusted intellectuals, the Cultural Revolution was an attempt to turn China into a utopian paradise run by and for workers. …

“Ji belongs to the generation that studied at the Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) in Beijing in the first years after it reopened. Like the other painters in this group, he learned the state-sanctioned style of Socialist Realism and then elected to unlearn what he had absorbed in order to reinvent himself. … He secretly studied calligraphy — which was considered intellectual, bourgeois. …

“He opened it up and used it to respond to current events, such as post-revolutionary China’s massive Three Gorges Dam Project and the consequent displacement of more than 1.5 million people. …

“As long as Ji continued to work in the tradition of Chinese landscape painting, Western audiences may have seen his views of displacement and protest, wayfarers carrying all their possessions, and melancholic ghosts as foreign to their experience.

“This is why Ji’s change is radical. He decided to take on the Western tradition of painting in order to suggest that his subject matter is global, rather than local to China. … While the traumatic social upheaval caused by the Three Gorges Dam Project is still very much on Ji’s mind, as evidenced by painting titles such as ‘Migrant Worker’s Tent,’ ‘Satellite Dish on a Bed,’ and ‘Everything Moved Outside,’ new things are happening in his work.

“Three paintings signal a departure for Ji: two depictions of flowers (‘Sunflower Turned Its Back’ and ‘Early Spring Bloom 2020’) and a three-quarter-length view of a standing man — and my favorite work — ‘The Man with Glasses.’ …

“Against a mottled brown, violet, and gray-blue abstract ground Ji has depicted an elderly man in blue pants and a long blue jacket over a pale blue shirt. The man is looking down, his hands in his pockets, and we cannot see his eyes. His head seems too large for his body, a deliberate choice by the artist. The shirt becomes a series of dry brushstrokes near the bottom and the gray-blue pants are largely unpainted. The jacket’s color reminds me of the blue surgical scrubs worn by doctors, which folds another level of feeling into the painting. The fact that the portrait resists a reductive reading is important to the change in Ji’s work and thinking.

“The premier coup approach is in keeping with ink painting, which cannot be revised or layered, but in his use of paint he works differently, as seen in the mottled background and single dry brushstroke used to separate the front pockets of the shirt. The incompleteness of the man set against a dark, fully painted abstract ground seems both a formal and emotional decision. The man is ephemeral, while the dark, inanimate ground is permanent. The evocation of change and transience is also inherent to Ji’s paintings of sunflowers and blossoming branches. In these works, he meditates on the relationship between forced change and inescapable transformation.”

More paintings at Hyperallergic, here. No firewall. Subscriptions welcomed.

It was interesting to me that “Everything Moved Outside” (2022) makes this reviewer think of the migrant life. For me “everything moved outside” means Covid. Would love to hear more reactions to the paintings shown at Hyperallergic.