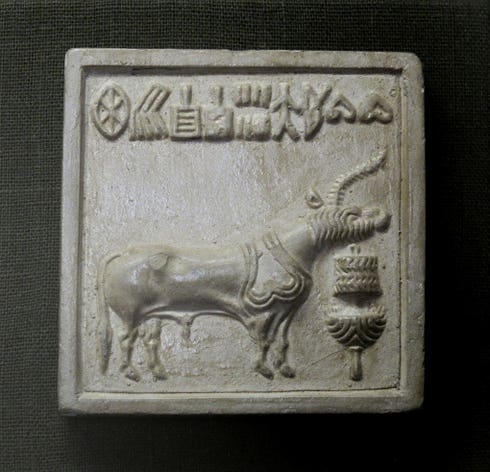

The earliest recognized form of “written” communication may have been small bits of clay, called tokens. This charming one is from the Indus Valley.

Nowadays, one reads almost too much about artificial intelligence, AI. I myself have an ever increasing list of things I’d rather not have AI managing for me. But using it to translate ancient texts is one application that seems to make perfect sense.

Ruth Schuster writes at Haaretz, “Understanding texts written using an unknown system in a tongue that’s been dead for thousands of years is quite the challenge. Reconstructing missing bits of the ancient text is even harder. …

“Filling in missing text starts with being able to read and understand the original text. That requires much donkey work. Now an Israeli team led by Shai Gordin at Ariel University in the West Bank has reinvented the donkey in digital form, harnessing artificial intelligence to help complete fragmented Akkadian cuneiform tablets.

“Their paper, ‘Restoration of Fragmentary Babylonian Texts Using Recurrent Neural Networks,’ was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in September.

“ ‘Neural networks’ … means software inspired by biological nervous systems. The concept dates back more than 70 years. … The base concept is to teach machines to learn, think and make decisions. In this case, the computer decides on the plausible completion of missing text. …

“Gordin and the team feed their machine transliterations of the extant Babylonian texts i.e., what the text would have sounded like.

“Then what? When it comes to missing bits in a papyrus or tablet, humans can intuit that “’…ow is your moth…’ isn’t a query into the well-being of your mothball.

With machines, it’s all about mathematics and probabilities based on knowledge gained so far. …

“It may have been trading that inspired the earliest recognized form of communication: ‘pseudo-writing’ on small bits of clay in Mesopotamia around 7,000 years ago. The clay bits, called tokens, were shaped into simplistic imagery such as a cow or other ancient commodities. …

“Then we start seeing abstract signs; repetitive strokes or depressions are interpreted as numbers (price, perhaps); and possibly also personal names, using the first sounds of different imprints to put together words you can’t draw. …

“Anyway, after pseudo-writing came proto-writing: figurative proto-cuneiform inscribed on tablets, which arose about 5,500 years ago in the city of Uruk. … Within mere centuries, proto-cuneiform evolved to become increasingly schematic and Sumer was apparently where it happened, [Gordin] says. And figurative hieroglyphic script began to appear in ancient Egypt at about the same time, about 5,000 years ago. …

“By the time cuneiform became a thing, writing had passed the stage of ‘Sheep : four : Yerachmiel’ and reached the stage of official records, letters and formulaic recounts of the wondrousness of the ruler. …

“For cuneiform, we have the gargantuan multilingual text at Behistun, Iran. Darius the Great had his exploits described in three different cuneiform scripts. [The] Behistun text was monumental: 15 meters (49 feet) high by 25 meters wide, and 100 meters up a cliff on the road connecting Babylon and Ecbatana, all to describe how Darius vanquished Gaumata and other foes. …

“And over decades, linguists slowly interpreted the languages of Babylon and Assyria, thanks to Darius’ monumental ego. …

“Interpreting a dead language is a mathematical game, Gordin says. … Neural networks are a computerized model that can understand text. How? They turn each symbol or word into a number, he explains. …

“When humans reconstruct missing text, their interpretation may be subjective. To be human is to err with bias, and quantifying the likely accuracy of the completion is impossible. Enter the machine. …

“The machine proved capable of identifying sentence structures – and did better than expected in making semantic identifications on the basis of context-based statistical inference, Gordin says. Its talents were further deduced by designing a completion test, in which the machine-learning model had to answer a multiple-choice question: which word fits in the blank space of a given sentence.”

Not sure how many readers are into that kind of thing, but I do find it intriguing. More at Haaretz, here.