Photo: Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“The Wealth of the Nation,” by Seymour Fogel, 1942, located in the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building, Washington, DC.

I’m a huge fan of the giant New Deal murals that gave brilliant artists work to do in lean times. I suppose the art has always been in danger of being covered over or removed as post offices and other public building have been remodeled. But right now the danger seems to be coming from the federal government’s current push to rewrite history.

Gray Brechin writes at the Living New Deal website that the federal government aims to sell the “Sistine Chapel” of New Deal art.

The murals of Ben Shahn, Brechin says, “in the old Social Security Administration headquarters in Washington, DC, were a problem, a docent privately told me when I toured the building in 2012.

“The building, which faces the National Mall, was by then occupied by the Voice of America. Visitors from around the world made reservations to tour the building as had I. Some of Shahn’s murals, painted when the building opened in 1940, the guide told me, suggested to visitors that poverty and racism existed in the land of the free.

“But Shahn and other artists commissioned to embellish the building also showed how Roosevelt and Frances Perkins’ Social Security programs had not only alleviated those problems, but had distributed America’s abundance so as to give everyone, rather than a few, a richer and more secure life than they had known before the New Deal.

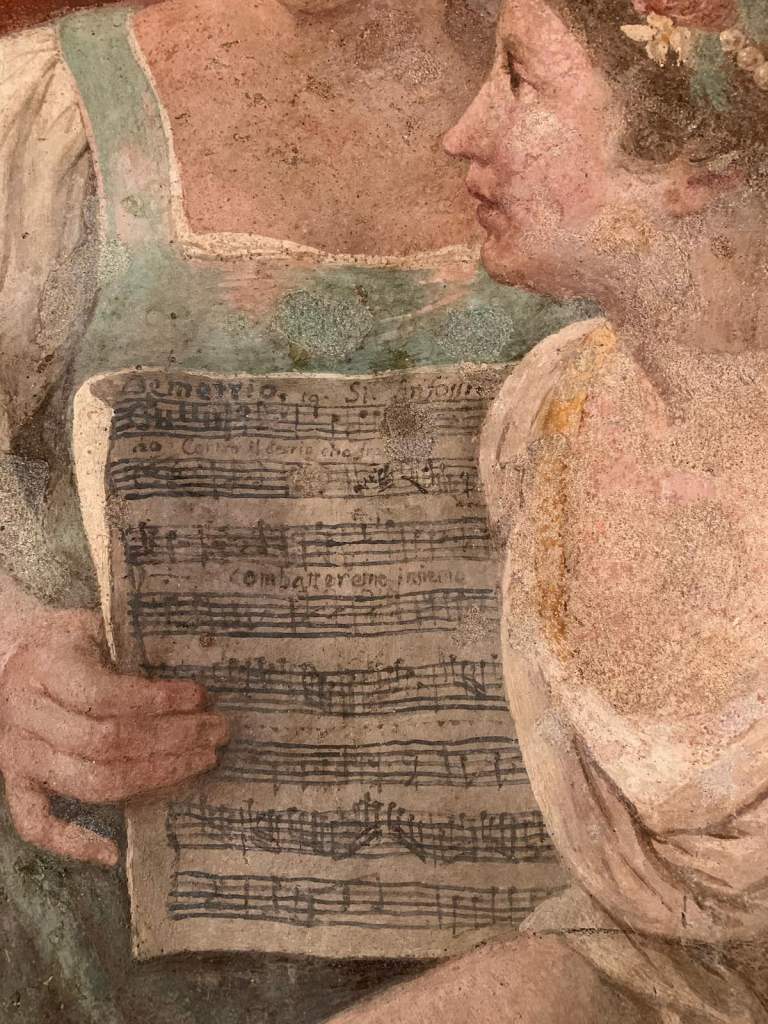

“Shahn’s fresco series ‘The Meaning of Social Security,’ is the most prominent of the murals in the now renamed Wilbur J. Cohen Building. Other artworks also carry themes of security and American life, among them ‘The Security of the People’ and ‘Wealth of the Nation’ by Seymour Fogel, ‘Reconstruction and Well-Being of the Family,’ by Philip Guston and granite reliefs by Emma Lu Davis. Some artworks were inaccessible when I toured the building.

“With Voice of America workers abruptly evicted on March 15 of this year [2025] and the agency itself facing extinction, the public is now forbidden access to the building altogether. The current administration hopes to speedily dispose of it and three others in the vicinity by the end of the year. A buyer could demolish the building. … Planning guidelines, reviews and preservation itself matter little if at all.

“As Timothy Noah explains in the New Republic … the General Services Administration (GSA), which owns the Cohen Building has itself been gutted in the administration’s drive to, in Grover Norquist’s words, ‘drown the government in the bathtub.’

“That Shahn’s murals depict a harsh reality worried me well before the administration began editing displays and signage that cast a less than a flattering light on US history at the Smithsonian Museums, National Parks, and other federal institutions. That federal buildings could be sold wholesale also concerned me more than a decade ago when the US Postal Service began quietly disposing of historic post offices, many of them containing New Deal art.

“One of those buildings, now in private hands, is the monumental Bronx General Post Office for which Ben Shahn and his wife Bernarda Bryson painted thirteen murals in 1937 depicting laboring Americans while Walt Whitman, painted at one end of the once-stately lobby, lectures those workers on their responsibility to democracy. Closed in 2013 and sold twice since then, the future of that structure, like the old Social Security Building, remains unclear, with development plans in the works.

“Once among America’s foremost painters, Ben Shahn’s artistic stock fell with the rise of abstract and pop art after World War II. Abstraction had little room for the kind of social realism in which Shahn and Bryson were masters.

“A recent exhibition at New York City’s Jewish Museum spanning Shahn’s career was testimony to Shahn’s lifelong concern for social justice and the issues addressed by the New Deal.

“Dr. Stephen Brown, a Jewish Museum curator, says that ‘Ben Shahn is one of the great American artists of the twentieth century who believed in the value of dissent and the essential function of art of a democratic society.’

“Himself an immigrant from Lithuania, Shahn’s two great mural cycles depicting his hopes for his adopted country are closed and off limits to the very public which paid for and ostensibly owns them. Gracing buildings that the present administration values only for the real estate beneath them, Shahn’s art and that of others … now face an uncertain future.”

Brechin adds that if anyone wants to help save the Wilbur J. Cohen Building, they may “sign and share the petition.” More at Living New Deal, here.

I have previously written about reviving hidden or forgotten New Deal murals — as in one post about Harlem, here.