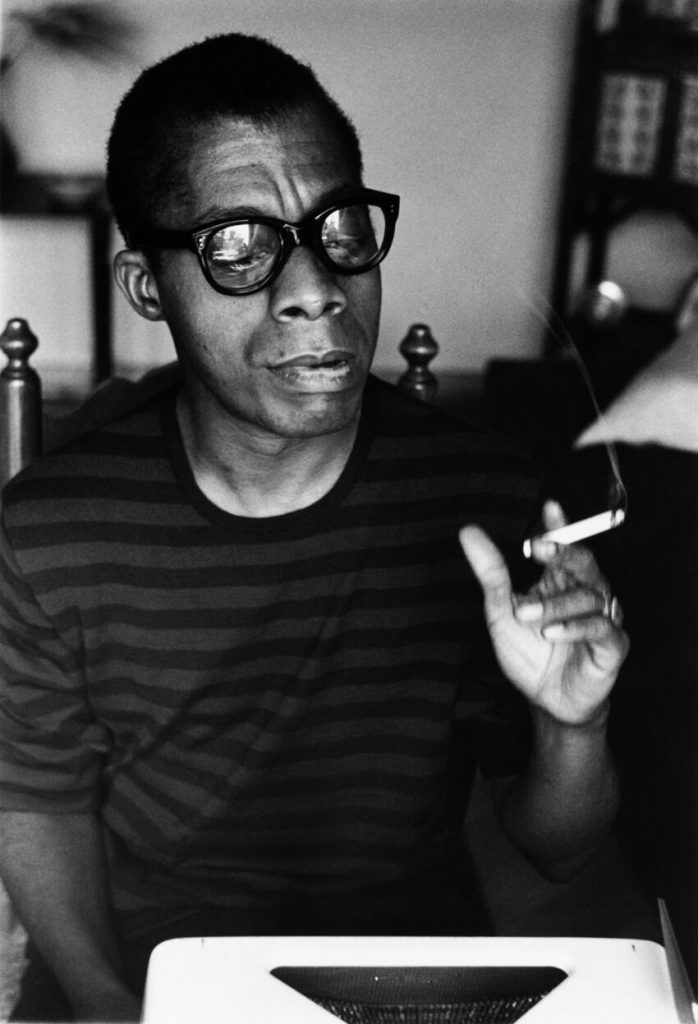

Photo: Sedat Pakay, Hudson Film Works II.

James Baldwin in Istanbul in 1966.

James Baldwin didn’t kid himself about life in America for a gay Black man in the 1960s. He traveled widely and lived for long stretches in countries he found more hospitable. (A 2016 post, here, addresses an effort to preserve a house he bought on the Côte d’Azur.)

I knew about France but not Turkey, which Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi writes about in the Yale Review.

At the beginning of the “11-minute black and white documentary, James Baldwin: From Another Place, directed by Sedat Pakay and filmed in Istanbul in May 1970, … he turns his back to the camera and opens the curtains. A sharp Mediterranean light floods in. Baldwin scratches the small of his back, and we hear him say in voiceover: ‘I suppose that many people do blame me for being out of the States as often as I am, but one can’t afford to worry about that because one does, you know, you do what you have to do the way you have to do it. And as someone who is outside of the States you realize that it’s impossible to get out, the American powers are everywhere.’

“The camera pans over the glittering Bosphorus Strait as American ships glide silently through the passage connecting Asia and Europe.

“Pakay’s film has long been almost impossible to see in the United States, aside from a short clip on YouTube. But in February, it began streaming on the Criterion Channel, and its reappearance is a useful occasion to re-examine one of the most important, and yet relatively unknown, aspects of Baldwin’s career: his time in Turkey.

“At the time Pakay made his film, Baldwin had been living in Istanbul intermittently for almost a decade. He first arrived there in 1961, broke, emotionally spent, and struggling to complete his third novel, Another Country. The Turkish actor Engin Cezzar, who had met Baldwin in New York in 1957 when he was cast as Giovanni in the Actors Studio adaptation of Giovanni’s Room (Baldwin’s second novel), had given him an open invitation to visit, and following a demoralizing trip to Israel, Baldwin showed up on Cezzar’s doorstep.

“He quickly made himself at home, and over the next ten years lived irregularly in Istanbul, Erdek, and Bodrum, socializing with the Turkish intelligentsia and a small circle of Black artists and activists who were living in Turkey or passing through.

“Istanbul offered Baldwin a refuge during the tumultuous decade of the 1960s. In a 1970 conversation with Ida Lewis for Essence magazine, Baldwin said of his decision to move to the city, ‘It was very useful for me to go to a place like Istanbul at that point in my life, because it was so far out of the way from what I called home and the pressures.’ …

“Baldwin had first left the United States, for Paris, in 1948, and had lived out of the United States for years prior to his arrival in Istanbul. But the clarity and safety afforded by his time there allowed him to more sharply articulate America’s assaultive realities and to give expression to the connections between his personal wounds and the scars of racialized political history. …

“[His] layered inner landscape mirror the city’s multifaceted character, with its refusal of neat distinctions between tradition and modernity, East and West, Christianity and Islam.

“Istanbul was a liminal space of healing for Baldwin, a writing haven that he saw as having saved his life. As [Magdalena Zaborowska, author of James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade] notes, this may explain why the Baldwin we see in Pakay’s documentary is far more relaxed and at ease than the Baldwin we are accustomed to seeing in American media from that era.

“And yet, Baldwin’s decade in Turkey remains an enigma and a lacuna in our collective imagination. Zaborowska’s is the only book-length treatment of Baldwin’s time there, and even people familiar with Baldwin’s writing are often unaware he ever lived in Istanbul. … What does the warm, vulnerable, and playful Baldwin captured on film by Pakay tell us about his need to leave America time and again in search of safety?

“The respite Turkey offered Baldwin, combined with Istanbul’s vibrancy and the warmth with which he was received, sparked one of the most prolific periods of his artistic life. In 1961, when he first arrived, he was haggard and exhausted.

“His trip to Israel had deepened his disillusionment with Christianity, and he was still mourning Eugene Worth, a Black socialist and dear friend, who, in 1946, had killed himself by jumping off the George Washington Bridge. In addition, Baldwin had been trying without success to complete Another Country, his courageous and groundbreaking exploration of bisexuality and interracial love.

“Worth’s death, which Baldwin memorializes in Another Country, had devastated Baldwin for years, and he had tried and failed again and again to finish the novel until he was delivered from the strain of severe writer’s block in Istanbul. Baldwin wrote the book’s final sentence while at a party at Cezzar’s house in what he described as ‘the city which the people from heaven had made their home.’ …

“The years Baldwin spent off and on in Turkey coincided with one of the country’s most vibrant and expansive periods. The 1950s in Turkey had been a period of economic decline, ruthless authoritarianism, and iron-fisted censorship, a confluence of negative forces that gave rise to mass mobilization and to student-led popular protests. …

“By 1965, free elections had been restored, and liberal constitutional reform had significantly expanded freedom of speech. The nation’s position as a strategic U.S. ally had been salvaged, but its cultural flowering continued, along with anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist movements similar to those that were emerging elsewhere around the world. Baldwin’s work and lived experience spoke directly to the political and aesthetic debates of the time. In Turkey, in a context of cultural ferment, Baldwin was revered as a major American and transnational writer, rather than being put in a position of having to prove his legitimacy over and over.

“Still, even in Turkey, Baldwin could not fully escape America. During the Cold War, relations between the United States and Turkey were founded on military collaboration and cooperation; the United States sent ships to Turkish waters to counter the threat of Soviet expansion, making Turkey a source of anti-Soviet military aid. As Baldwin said to Sedat Pakay, ‘American powers are everywhere.’ His feelings fluctuated between entrapment, the sense that no matter how far he traveled from the violence in the United States he could not, existentially speaking, ‘get out,’ and the feelings of transcendence and revival that Cezzar’s warm hospitality and Turkey itself afforded him.”

More at the Yale Review, here. No firewall.