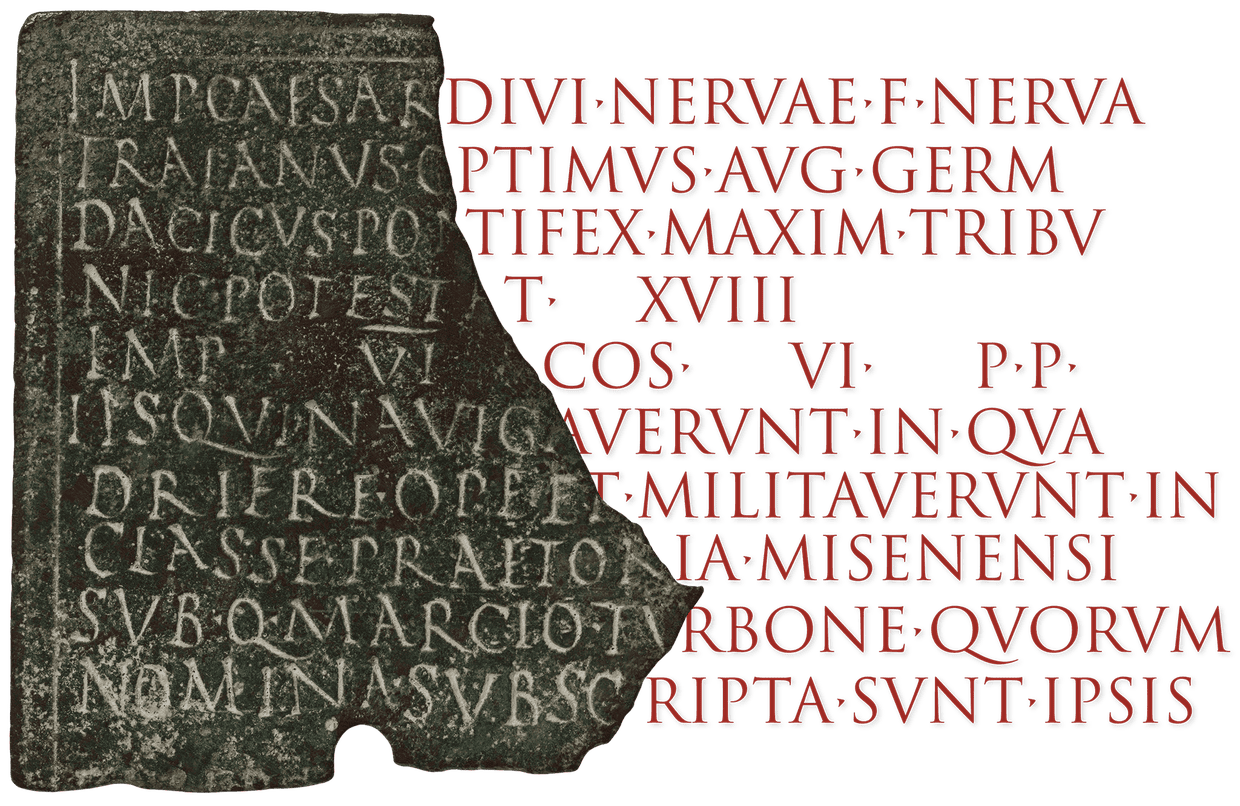

Photo:The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Google’s Aeneas AI program proposes words to fill the gaps in worn and damaged artifacts.

Whenever I start to worry that Google has too much power, it does something useful. Today’s story is about its artificial intelligence program Aeneas, which can make a guess about half-obliterated letters in ancient inscriptions.

Ian Sample, science editor at the Guardian, writes, “In addition to sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a freshwater system and public health, the Romans also produced a lot of inscriptions.

“Making sense of the ancient texts can be a slog for scholars, but a new artificial intelligence tool from Google DeepMind aims to ease the process. Named Aeneas after the mythical Trojan hero, the program predicts where and when inscriptions were made and makes suggestions where words are missing.

“Historians who put the program through its paces said it transformed their work by helping them identify similar inscriptions to those they were studying, a crucial step for setting the texts in context, and proposing words to fill the inevitable gaps in worn and damaged artifacts.

” ‘Aeneas helps historians interpret, attribute and restore fragmentary Latin texts,’ said Dr Thea Sommerschield, a historian at the University of Nottingham who developed Aeneas with the tech firm. …

“Inscriptions are among the most important records of life in the ancient world. The most elaborate can cover monument walls, but many more take the form of decrees from emperors, political graffiti, love poems, business records, epitaphs on tombs and writings on everyday life. Scholars estimate that about 1,500 new inscriptions are found every year. …

“But there is a problem. The texts are often broken into pieces or so ravaged by time that parts are illegible. And many inscribed objects have been scattered over the years, making their origins uncertain.

“The Google team led by Yannis Assael worked with historians to create an AI tool that would aid the research process. The program is trained on an enormous database of nearly 200,000 known inscriptions, amounting to 16m characters.

“Aeneas takes text, and in some cases images, from the inscription being studied and draws on its training to build a list of related inscriptions from 7th century BC to 8th century AD. Rather than merely searching for similar words, the AI identifies and links inscriptions through deeper historical connections. …

“The AI can assign study texts to one of 62 Roman provinces and estimate when it was written to within 13 years. It also provides potential words to fill in any gaps, though this has only been tested on known inscriptions where text is blocked out.

“In a test … Aeneas analyzed inscriptions on a votive altar from Mogontiacum, now Mainz in Germany, and revealed through subtle linguistic similarities how it had been influenced by an older votive altar in the region. ‘Those were jaw-dropping moments for us,’ said Sommerschield. Details are published in Nature. …

“In a collaboration, 23 historians used Aeneas to analyze Latin inscriptions. The context provided by the tool was helpful in 90% of cases. “’t promises to be transformative,’ said Mary Beard, a professor of classics at the University of Cambridge.

“Jonathan Prag, a co-author and professor of ancient history at the University of Oxford, said Aeneas could be run on the existing corpus of inscriptions to see if the interpretations could be improved. He added that Aeneas would enable a wider range of people to work on the texts.

“ ‘The only way you can do it without a tool like this is by building up an enormous personal knowledge or having access to an enormous library,’ he said. ‘But you do need to be able to use it critically.’ “

More at the Guardian, here. Please remember that this free news outlet needs donations.