Photo: Wigtown, Scotland, Book Festival.

Book lovers who are traveling this year may want to think about visiting one of the “book towns” profiled recently in National Geographic. Ashley Packard collected seven that sound charming.

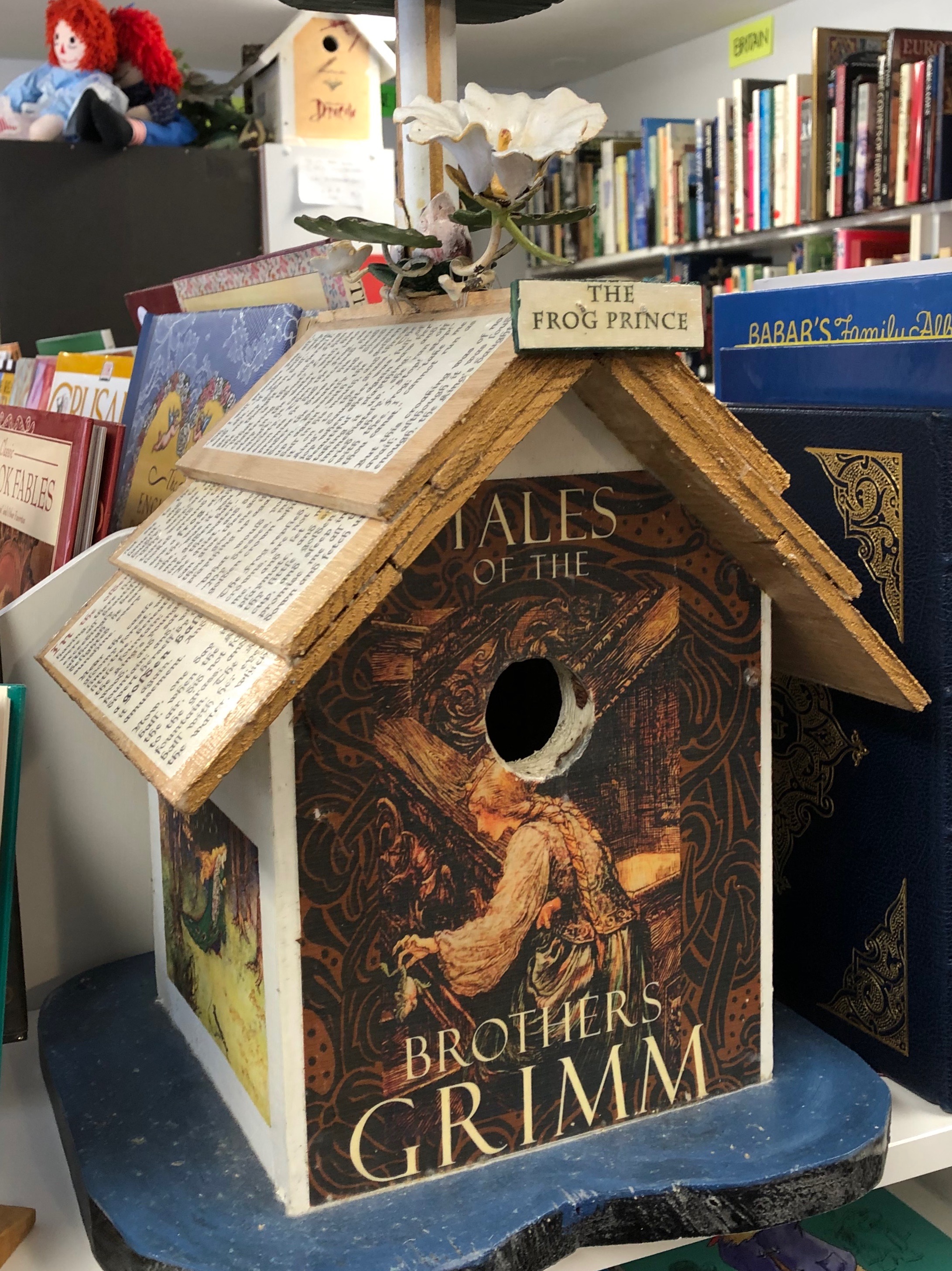

“1. In the Welsh village of Hay-on-Wye, where sheep outnumber people and books spill onto the streets, a quiet revolution began. Antiquarian and academic Richard Booth inadvertently launched a global movement when he began filling the empty buildings of Hay-on-Wye with secondhand books.

“What started as a single decision in 1961 to fill his sleepy hometown with secondhand books to sell in numerous empty buildings, turned into the birthplace of a global literary mecca uniting villages, bibliophiles, and dreamers alike. …

“Hay-on-Wye became the first ever ‘book town,’ supporting patrons who flocked to the shops. Booth, who crowned himself ‘King of Hay,’ inspired others to turn literature into lifelines for their little towns and villages. As word of his success spread, more towns around the world embraced the concept for their communities. Before long, the International Organization of Book Towns was formed in April 2001, though it had existed without the official designation for decades prior.

“The organization aims to raise public awareness of book towns through online information and a biennial International Book Town Festival. It supports rural economies by facilitating knowledge exchange among booksellers and businesses, encouraging the use of technology, and helping to preserve and promote regional and national cultural heritage on a global scale.

“By definition, a book town is ‘a small, preferably rural, town or village in which secondhand and antiquarian bookshops are concentrated.’ … Today, there are dozens of towns with the designation, from Pazin, Croatia, to Featherson, New Zealand. These selected and approved locations take pride in their history, scenic beauty, and contributions to the literary world. …

“2. In a small village tucked away in the hilly countryside of Belgium, Redu is now celebrating its 41st anniversary since becoming the second book town in 1984. This idyllic village is described as, ‘fragrant with the scent of old paper.’ … It, along with its hamlets Lesse and Séchery, were recently added to the ‘Most Beautiful Villages in Wallonia‘ list in July 2024.

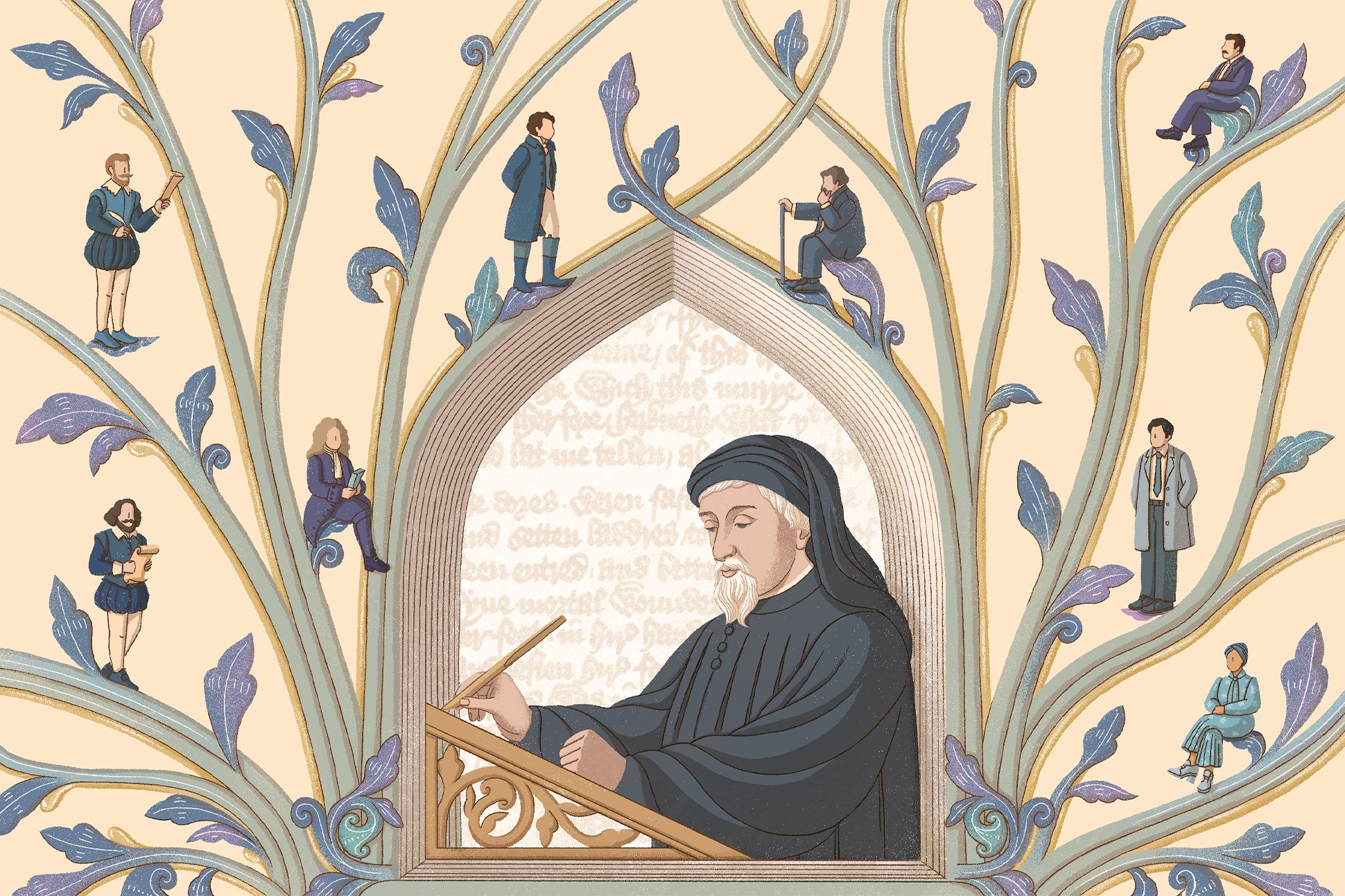

“3. [In Scotland] nestled on a hill overlooking the sea along a rugged coastline, woodlands, and forests, lies Wigtown, celebrating 20 years as ‘Scotland’s Book Town.’ … It has 16 different types of book shops, many secondhand, that participate in an annual Spring Weekend in early May, a community festival in July, a market every Saturday from April through late September, and the annual Wigtown Book Festival in late September through early October. The 10-day literary celebration was founded in 1999 and now features more than 200 events, including music, theater, food, and visual arts.

“4. Turup [in Denmark] is situated 37 miles north of the Danish capital of Copenhagen, between the sea and a fjord, and has a population of 374 people. Here, locals put out the best and most high-quality secondhand books from donations out for sale along the rural roads of the 10 different shops (if you can call them that) for purchase. These ‘bookshops’ include a garage, a workman’s hut, a disused stable, a bookshelf on a farm entrance, and even a newly restored railway station. Some of these stalls process transactions on a self-help and honesty basis where customers leave their change in a jar in exchange for their purchases. The Torup Book Town Association hosts an annual Nordic Book Festival with book readings from authors, contemporary short films, cultural events, and more.

“5. Surrounded by stunning landscapes, rolling hills, and vineyards is the quaint town of Featherston [New Zealand] … became officially recognized as a book town in 2018. It is famously known for the annual book festival held in May. They have initiatives dedicated to fostering community growth, inspire reading, writing, and idea-sharing across Wairarapa and Aotearoa, New Zealand.

“6. Offering year-round bookstalls and literary festivals, the village of St-Pierre-de-Clages is home to Switzerland’s only book village. ‘Le Village Suisse du Livre,’ translated to ‘The Swiss Book Village,’ is home to a large secondhand market, along with authors, thematic exhibitions, activities for children, and a renowned Book Festival that has been hosted every last weekend of August since 1993. … This festival takes place over three days and attracts visitors from all over French-speaking Switzerland and neighbors. It offers insight into book professions such as calligraphy and old printing techniques, a welcoming space for writers and publishing houses to meet, and various artists to display their work.

“7. The former garrison town of Wünsdorf [in Germany] is known as ‘book and bunker city’ due to the historical sites, buildings, book shops, cafes and tea rooms, and lively cultural life. Nestled about 12 miles south of Berlin, the town offers year-round events, readings, exhibitions, military vehicle meetings, and currently five different bunker and guided tours. Wünsdorf was established as an official member of the International Organization of Book Towns in 1998 thanks to its three large antiquarian shops that boast of a wide array of literary treasures on topics such as poetry, philosophy, classical literature, and many more.”

More at National Geographic, here. Great photos, as you would expect from National Geographic.