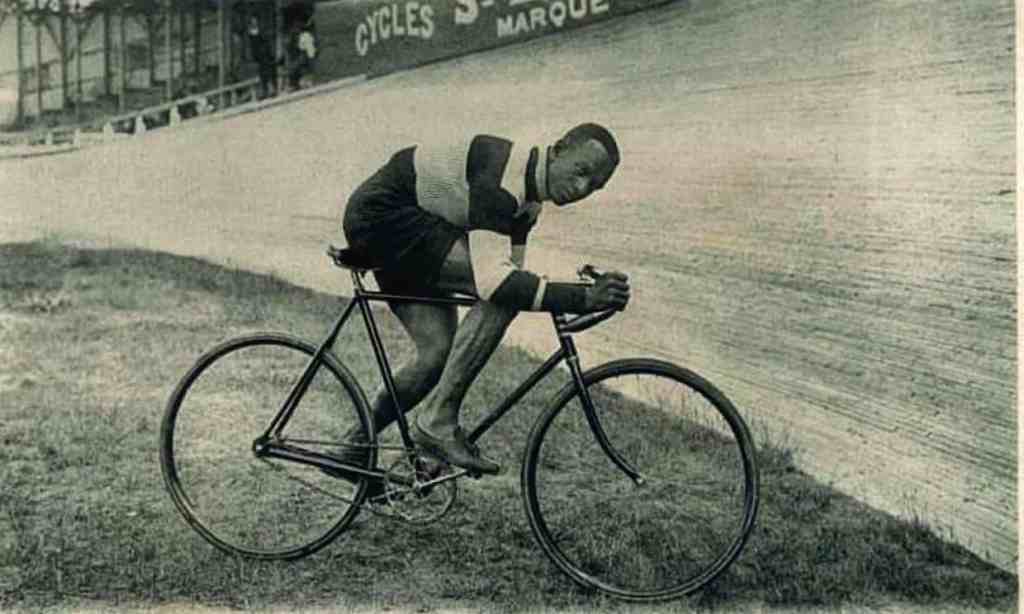

Photo: via Robert Turpin.

Woody Hedspeth was one of several Black American cyclists in the early 20th-century to move abroad to further his career.

A country shoots itself in the foot when it pushes away talent. I’m thinking of asylum seekers who may have something to offer. I’m thinking of Black talent going to Europe to find a more welcoming and level playing field — writer James Baldwin, for example, singers Josephine Baker, Marian Anderson, and Paul Robeson.

Today I’m learning about Black bicycling champions turning to Europe in the early days of the competitive sport.

Rich Tenorio writes at the Guardian, “When cycling first took the US by storm in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Black Americans joined in the new pastime. One Black cyclist, Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor, became a world champion in 1899. Yet American cycling installed a color line in professional racing. Opportunities became so limited that Black competitors had to take them wherever they could find them – including on the vaudeville stage and in Europe. Their story is documented in a new book, Black Cyclists: The Race for Inclusion, by Robert J Turpin, a professor of history at Lees-McRae College in North Carolina.

“ ‘We fall into the trap that history is linear,’ Turpin says. ‘With race relations, we think about the end of the Civil War: “Slavery ended, and things gradually got better and better for Black people.” My book shows what we already know: Things actually got worse for Black people in the US, especially from the 1880s through the 1920s … It got harder for Black cyclists to compete as professionals or even win prize money in general.’

“Turpin is a cyclist himself, and his college features a cycling studies minor, which he believes is the only such program in the US. His interest in the history of cycling extends to how it has been marketed over the decades – the subject of his previous book. …

“Turpin raises another issue: a lack of diversity in contemporary cycling. The book cites a 2020 USA Cycling survey of over 7,000 members in which just 3% reported they were Black or African American. Such underrepresentation extends to the [Olympics] and the Tour de France, where [in July] Biniam Girmay became the first Black African stage winner in the race’s 120-year history. Yet the book notes the increasing impact and influence of Black elite competitors such as 11-time national champion Justin Williams and the first Black female professional cyclist, Ayesha McGowan.

“Before attending graduate school at the University of Kentucky in 2009, Turpin learned about Taylor, whose exploits in cycling began as a teenager in Indianapolis, and crested with a world championship in the one-mile sprint in Montreal. In doing so, he became the first Black American world champion in any sport and his achievements were chronicled in an autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World. ‘He was an international superstar,’ Turpin says. …

“Several years later, Turpin returned to Taylor’s story. By that time, additional primary sources had been made publicly available through digitization. Turpin learned more about not only Taylor, but also his predecessors and peers. …

“Massachusetts became a venue for early Black success in cycling. David Drummond regularly won Fourth of July races in Boston. Taylor used his winnings to buy a home in Worcester – and the city’s first automobile. Katherine ‘Kittie’ Knox, a seamstress turned racing star, was famous for her self-designed outfits and her endurance. Knox illuminated challenges faced by cyclists who were both Black and female.

“ ‘If you were Black and a woman, those were two big strikes against you,’ Turpin says. …

“In 1894, a prominent nationwide cycling organization called the League of American Wheelmen, … barred all Black cyclists except Taylor from professional racing. The ban was not officially repealed until 1999 by the organization, which had been renamed the League of American Bicyclists.

“The book shows the ways in which Black cyclists responded. These included criticizing the decision in the Massachusetts state legislature and forming Black cycling leagues.

“ ‘I stress their agency,’ Turpin says. ‘I do not talk about them as victims. They were resourceful in figuring out alternative ways to still make a living and find social mobility.’ …

“Unlike Jim Crow America, international venues welcomed Black participation as professionals. Taylor left for France and Australia, and named his daughter Sydney after the city where he felt most welcome. Fellow racer Woody Hedspeth followed Taylor to France – and while Taylor returned to the US, Hedspeth remained in Paris.”

More at the Guardian, here. No firewall.