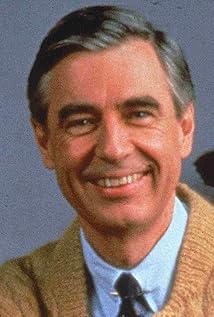

Photo: EllaJenkins.com.

Ella Jenkins is the best selling individual artist in the history of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. She introduced children to music from around the world and never talked down to them.

Today we learn about a folksinger whose unorthodox approach revolutionized music for children. Her name is Ella Jenkins.

Laurel Graeber writes at the New York Times, “When Ella Jenkins began recording young people’s music in the 1950s and ’60s, her albums featured tracks that many of that era’s parents and teachers would probably never have dreamed of playing for children: a love chant from North Africa. A Mexican hand-clapping song. A Maori Indian battle chant. And even ‘Another Man Done Gone,’ an American chain-gang lament whose lyrics she changed [into] a freedom cry.

“ ‘She found this way of introducing children to sometimes very difficult topics and material, but with a kind of gentleness,’ said Gayle Wald, a professor of American studies at George Washington University and the author of a forthcoming biography of Jenkins. ‘She never lied to them. She certainly never talked down to them.’

“Jenkins’s unorthodox approach became a huge success: … A champion of diversity long before the term became popular, Jenkins helped revolutionize music for the young, purposefully encouraging Black children. In addition to introducing global material, which she often recorded with children’s choruses, she wrote original, interactive compositions like ‘You’ll Sing a Song and I’ll Sing a Song,’ now part of the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry. …

“You might think that Jenkins, [100], would now want to relax. … What she would really like to do — although her fragile health prevents it — is to perform again herself. ‘I want to get well and get back on the job, where I’m working with other people, working with children,’ she said. ‘I work with them, and they work with me. I enjoy work.’

“Jenkins’s efforts, which comprise more than 40 recordings, began on Chicago’s South Side, where she grew up. Although never formally trained as a musician, she learned harmonica from her Uncle Flood and absorbed a variety of musical traditions through neighborhood moves and jobs as a camp counselor. After graduating from what was then known as San Francisco State College, she directed teen programs at the Chicago Y.W.C.A., which helped cement her love for children. Her street performances led to an offer to do young people’s music segments on local television, a debut that would be followed years later by appearances on shows like Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

“ ‘Her curiosity is so insatiable,’ said Tim Ferrin, a Chicago filmmaker who is completing a documentary, Ella Jenkins: We’ll Sing a Song Together. He added, ‘I think she saw herself as a conduit, as somebody who could then share that enthusiasm, share that understanding.’

“Often called ‘the first lady of children’s music,’ Jenkins captivated her listeners because she presented music not as lessons but as play. A charismatic performer whose accompaniment often consisted of only a baritone ukulele and some percussion, she encouraged her young audiences not to sit still but to get up and move. Using a signature call-and-response technique that she adapted from African tradition and artists like Cab Calloway, she engaged her listeners in a musical conversation, even if they didn’t understand what they were singing.

“ ‘She made it very immediate and not exotic,’ said Tony Seeger, an ethnomusicologist and the founding director of Smithsonian Folkways. … At a Chicago convention of the National Association for the Education of Young Children in the 1990s, he recalled, so many members tried to crowd into a Jenkins concert that the organizers shut the doors. Those excluded responded with frenzied knocking.

“ ‘It was astounding, her popularity, and also the insistence with which these preschool teachers were pounding on the door,’ Seeger said, chuckling in a video interview. ‘I mean, you don’t think that they would do that sort of thing. But they did.’ ”

More at the Times, here.