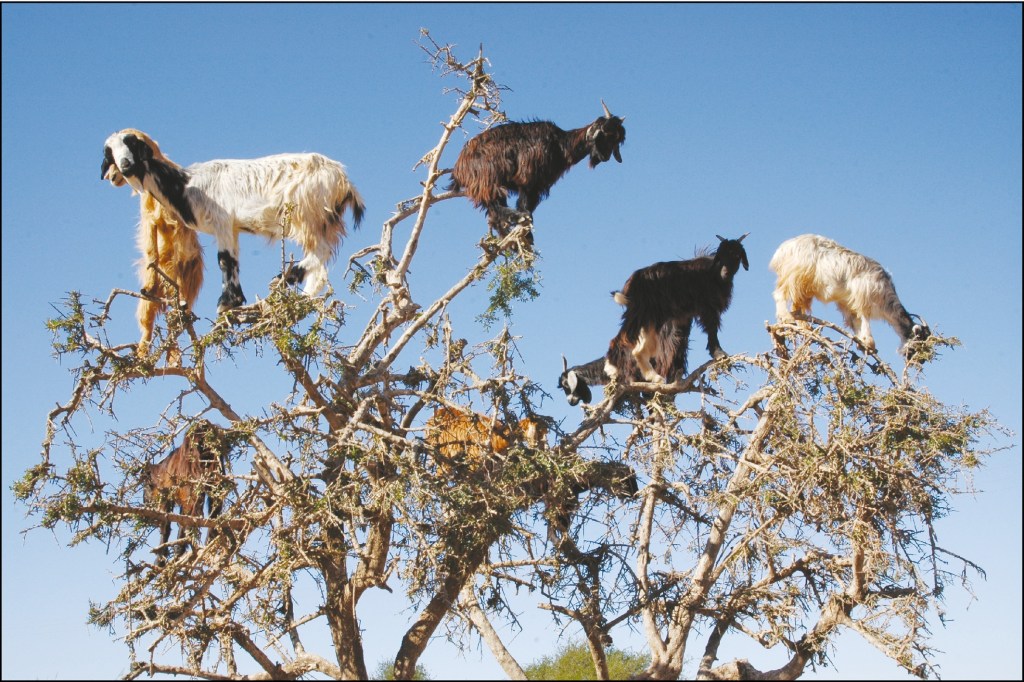

Photo: H Garrido/EBD-CSIC.

Goats grazing on an argan tree in southwestern Morocco. They disperse seeds during rumination, which is one of the ways the trees extend their presence.

When I first saw the picture above, I knew I needed it for the blog. An internet search revealed plenty of touring companies that offer customers photo ops with climbing goats.

But there is more to these guys than that.

Here’s a study by Miguel Delibes, Irene Castañeda, and José M Fedriani from an Ecological Society of America journal called Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. It explains that the goats’ role on the planet goes beyond being cute.

“Most people are familiar with domestic goats (Capra hircus) climbing on rocks,” the authors write, “but few know they are talented tree climbers too. In temperate countries where green pastures abound, goats do not need to climb trees to forage, but in arid regions the only available forage is sometimes found on the tops of evergreen shrubs and trees. Furthermore, goats often like seasonal fruits and collect them directly from fruiting trees when fallen fruits have been depleted.

“In southwestern Morocco, where the average annual rainfall is only 300 mm (~12 inches), goats climb the endemic argan tree (Argania spinosa).

Herders assist kid goats in learning to climb and even occasionally prune the trees to facilitate climbing.

“During the autumn, when herbaceous vegetation is lacking, goats devote 74% of their foraging time to ‘treetop grazing.’ …

“We previously observed Spanish and Mexican goats grazing on short trees or shrubs, but in Morocco we were astonished to see between 10 and 20 goats regularly climbing thorny 8–10-m-tall argan trees, mostly defoliated after intensive grazing. The purpose of our research was to verify that goats regurgitated the nuts of argan fruits while ruminating. …

“Argan forests are ecologically and economically important in southern Morocco, which is a developing country. The forests serve as an effective barrier for the Saharan Desert and provide local people with wood, fodder for livestock, cooking oil, medicine, and cosmetic materials. …

“To extract the oily kernels, the fleshy pulp of the tree fruits must first be removed and the hard nuts broken manually. Most popular accounts [say] that to remove the pulp, traditional Berbers feed the fruit to goats so the nuts pass through the digestive system and the seeds can be collected from the manure. However, goats do not usually defecate large seeds, so we were skeptical. …

“We wondered whether goats, which are ruminants, might spit out the nuts while chewing their cud, as we had seen goats do when fed with olive (Olea europaea) and dwarf palm (Chamaerops humilis) fruits in Spain (unpublished data). Moroccan goat herders confirmed that goats regurgitated most argan nuts while ruminating, although regurgitations and excrement found on the ground are usually mixed, resulting in misunderstandings about the way the nuts were expelled.

“Why is it important that goats regurgitate and spit out seeds from the cud? For plants there are well-known reproductive benefits associated with dispersing their seeds far from the maternal parent, including a greater probability of seed and seedling survival. To successfully disperse, many plant species produce edible fruits that attract frugivorous vertebrates, which ingest the fruits and transport the seeds inside their body until they are released elsewhere by regurgitation or defecation. …

“The possibility of ruminant ungulates spitting out some viable seeds from the cud is not even mentioned in [many] comprehensive reviews. … To illustrate the potential of domestic ruminants to spit viable seeds from their cud, we supplied Spanish domestic goats with fruits differing in size and structure, corresponding to five species (six varieties) of plants, including five drupes or pomes (fleshy fruits) and one legume (pods). …

“For all the plant species, we recovered appreciable numbers of seeds that the goats had regurgitated, despite not being able to find all of the seeds, since the goats were not subject to controlled conditions. As might be expected, larger seeds were more frequently spat out during rumination. …

“Our observations suggest that almost any seed could be ejected during mastication, spat from the cud, digested, or defecated. We tested the viability of regurgitated seeds by incubating them in a solution containing tetrazolium chloride; the embryo and endosperm of most seeds (71.5%) were stained red, indicating they were viable after processing by goats. …

“In conclusion, many previous studies that investigated the role of ruminants as seed dispersers were based exclusively on dung analyses and may have underestimated an important fraction of the total number of dispersed seeds. Moreover, this fraction of seeds should correspond to plant species with particular fruit and seed traits (eg large linear dimensions) differing from those of plant species dispersed exclusively or mostly through defecation. Importantly, the seeds of some species are unlikely to survive passage through the ruminant lower digestive tract so that spitting from the cud may represent their only, or at least their main, dispersal mechanism. It is therefore essential to investigate the effectiveness of this overlooked mechanism of seed dispersal in various habitats and systems.”

Don’t you love the language they use? “Processing by goats”! More at Ecological Society of America, here. No firewall. I have removed citations, so check out the original if you want to know who discovered what.