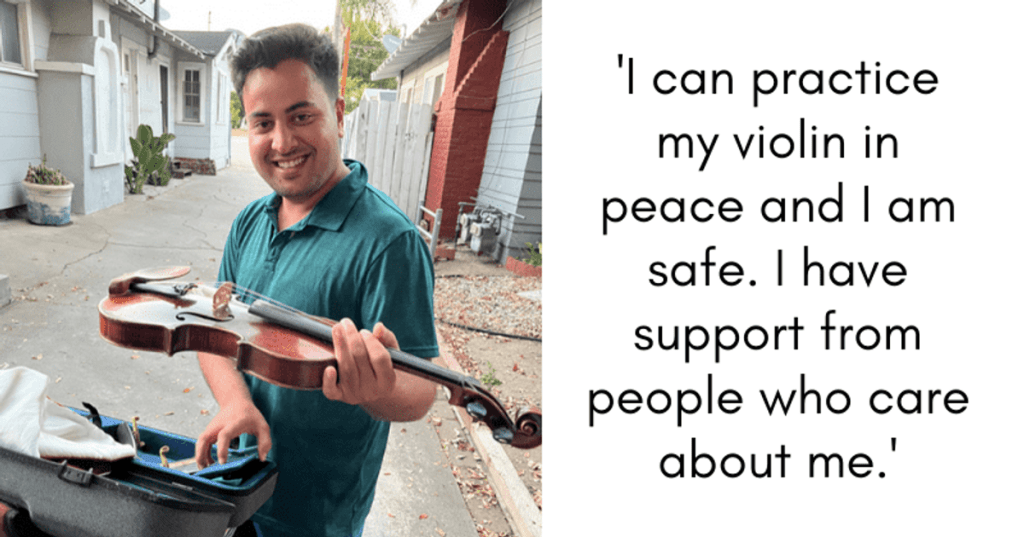

Photo: Twitter | @latifnaseer.

Ali Esmahilzada, an Afghan violinist, fled Kabul in 2022 amid the Taliban takeover. He arrived in Los Angeles without a violin. Latif Nasser delivered an antique violin from Jeremy Bloom and found a friend for life.

There are few positive stories about the aftermath of the abrupt 2022 US departure from Afghanistan. So, in sharing today’s article, I don’t want to minimize the suffering that continues there. For example, my friend Shagufa, the youngest of 11 children in a Herat family, was faced with getting her mother and all her sisters out, working with Marilyn Mosley Gordanier at Educate Girls Now. One of Shagufa’s sisters really had a target on her back, having trained as a police officer for the deposed government.

But at the Washington Post, we do find a nice story by Sydney Page about an Afghan who made it to the US.

“On a work trip in Upstate New York last May, Latif Nasser got an unexpected request from a colleague: ‘Can you hand-deliver an antique violin across the country?’ …

“The violin was going to an Afghan violinist who fled Kabul amid the Taliban takeover, and settled in Los Angeles with almost nothing but the clothes on his back. He left his violin behind.

“Nasser, [science journalist and co-host of Radiolab from] Los Angeles, agreed to help. The request came from Jeremy Bloom, a sound designer based in Brooklyn, who had heard about the struggling musician from a friend.

“Bloom happened to have a 110-year-old German-made violin collecting dust in his closet. He decided to offer it to the Afghan musician, who he knew would put it to good use.

“ ‘I was very lucky to be able to play that violin for a while, but I also felt guilty that it was sitting in a closet,’ said Bloom, adding that older violins are sometimes seen as more desirable than newer instruments. …

“The problem was, Bloom had no way of getting the violin to Los Angeles. ‘You do not want to ship an antique violin in the mail,’ he said, because he feared it would get damaged. …

“It took several weeks to get the instrument to the Afghan violinist, Ali Esmahilzada. ‘It felt like it took forever for us to coordinate,’ said Nasser, who — after several failed delivery attempts — became irritated when Esmahilzada asked if he could bring it to a mall. The musician didn’t seem eager to get the instrument, and Nasser began to wonder whether he even really wanted it.

“ ‘In a way, I was being protective of my friend Jeremy. … ‘This is the most beautiful gesture, giving someone this priceless violin for free.’

“After the mall plan didn’t work out, Nasser and Esmahilzada finally found a time to meet, and … it was immediately clear that ‘he wanted this violin so bad,’ Nasser said.

“Esmahilzada said he did not take his treasured violin with him when he left Afghanistan because he feared if the Taliban found his instrument at armed checkpoints throughout the city, they would ‘hurt me.’ …

“The Taliban has prohibited playing music in Afghanistan, and possessing an instrument is considered a crime. Esmahilzada, who has been playing the violin since he was 13, felt he had no choice but to flee his home country — and leave his family behind. ‘I was so scared.’ … He came to the United States on a Special Immigrant Visa with only a few belongings. …

“He was living in a small house with four Spanish-speaking roommates who he had trouble communicating with. He worked in the stockroom of a clothing store — which is why he asked Nasser to meet him at the mall. He ate eggs for every meal because it was the only thing he knew how to cook. …

“Nasser — whose parents immigrated to Canada in the early 1970s from Tanzania — empathized with Esmahilzada.

“ ‘It was so hard for my parents,’ said Nasser, explaining that kind strangers helped them get settled, and likewise, they went on to assist other immigrants.

“ ‘The more I heard his story and how deeply alone he was, I decided I could be that person for him,’ Nasser continued. … He invited Esmahilzada over to have dinner with his wife and two small children — which soon became a weekly invitation.

“ ‘It clearly meant a lot to him. He both needed it and was grateful for it,’ Nasser said. ‘It seemed like it was a gulp of water to a thirsty guy.’

“Nasser’s family started to feel like his own. … Life in America [had been so] difficult. He worked tirelessly to make a meager living, most of which he sent back to his family in Kabul. …

“Nasser and his wife helped him find an immigration lawyer, a laptop, some clothing and groceries. They also supported him as he sought a more stable job, and got himself a car. …

“For the first time in a long while, Esmahilzada said, he is hopeful about the future.

“ ‘I started from zero when I came to the United States,’ he said. ‘Now I’m happy. I have support from people who care about me. We have really kind people in the world.’ ”

More at the Post, here. To read without a firewall, click on Upworthy.