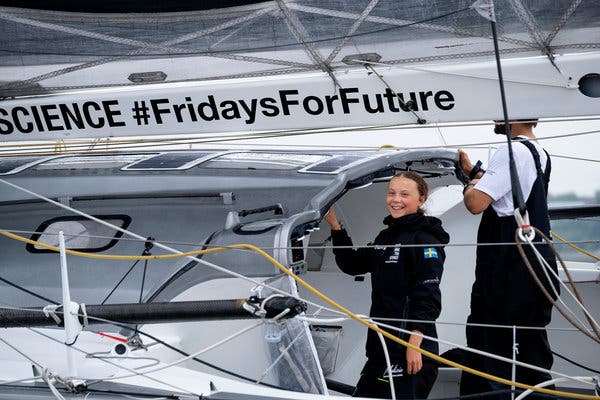

Photo: José Hevia.

Rambla Climate-House by architect Andrés Jaque in Molina de Segura, Spain.

Today’s article addresses how architecture can and should repair our ecological system. How in cities, for example, a comprehensive vision would extend beyond beautifying downtown to embracing the understanding that we are not the only species on the planet.

At El País, Miguel Ángel Medina interviews architect Andrés Jaque about buildings that can be good for the environment.

“For three years,” he says, “Andrés Jaque, 53, has been dean of the Graduate School of Architecture at Columbia University, one of the most cutting-edge centers in architectural innovation. The Madrid-born architect is spending his time at the university rethinking how buildings and cities should face climate change. He believes that we must commit to an ‘interspecies alliance’ and that buildings, beyond just being sustainable, should also contribute to repairing our ecology.

“Jaque has proposed several projects with this concept in mind, such as the Reggio School in Madrid — designed to create life within its walls and attract insects and animals. …

Andrés Jaque

“Architecture is the discipline that has most clearly assumed the responsibility of responding to the climate crisis. In the last 15 years, there’s been a radical transformation [in the field]: materials have gone from being sustainable to [repairing the ecology]. And [the architectural field] has revised its own mission, which is no longer to just build new buildings, but to manage the built environment. Additionally, it has brought about an intersectional vision: understanding that the material, the social, the ecological and the political are inseparable and that climate action has to coordinate these fronts of transformation. This has placed architecture at the center of environmental action.

Miguel Ángel Medina

“Do architects share this interpretation?

Jaque

There’s a part [of the field] that’s anchored in a heroic vision of modernity and another that’s commercial… but there’s another that has a political commitment to the planet. And [those who adhere to this] understand that architecture must respond not only to the most immediate circumstances of a commission, but also to action for the planet. …

“There are two systems: a material world of extractivism — which is a mix of carbonization, colonialism, anthropocentrism, heteropatriarchy and racialization — that’s currently collapsing. And, in the cracks of this system, another kind of architecture is emerging, which seeks alliances between species based on symmetry, which pursues a global regime of solidarity and which advances along a line of decarbonization that marks the esthetics, the materialities [and] the types of relationships that constitute contemporary culture. This is gaining undeniable strength. In the future, we’ll see a change that’s as important as the one that modernity once represented. …

Medina

“What do we do with urban planning, given so many extreme phenomena?

Jaque

“We’ve been pioneers in proposing a change of focus, from an emphasis on the city as a kind of stain on the territory, to a trans-scalar approach. This is a way of understanding [the physical structure that is] an urban block of apartments, the microbial relationships that occur in the bodies of those who live on that block, as well as the large networks of resource extraction that make life on that block possible.

“The city has lost the capacity to contain all realities, [which is necessary] in order to think in a climatic and ecosystemic way. And we need a new model that allows us to understand that what happens on a molecular scale has implications on the scale of bodies, buildings, streets, neighborhoods, the planet and the climate. Designing [cities] in a trans-scalar way requires changes in the methodologies of architecture, which we’re exploring. …

“Cities are going through a period of great transformation. A transformation in which the city has to be understood as something physically porous, which allows for the circularity of water, which contributes to multiplying life… a transformation of materiality that promotes a flow of materials that also contributes to the health of bodies. [We require] a very different way of urbanizing the air – in such a way that it’s understood that there’s a direct relationship between our lungs and the climate – and a commitment to the generation of diverse and empowered living environments. The main difficulty is how to do this quickly, so as to mitigate the impact of the climate and environmental crises.

Medina

“What’s this new ‘interspecies diplomacy’ that you advocate in favor of?

Jaque

“Humans are just one of many forms of life. And the idea that humans can decide to sacrifice the rest of the species to serve their own interests has been shown to be harmful. Understanding that we’re dependent on many other species — and that we’re actually inseparable from them — is more realistic. We depend on the quality of the soil, on the ecosystems. An interspecies alliance based on protecting the living conditions of diverse species is beneficial for all life on the planet.”

More at El País, here.