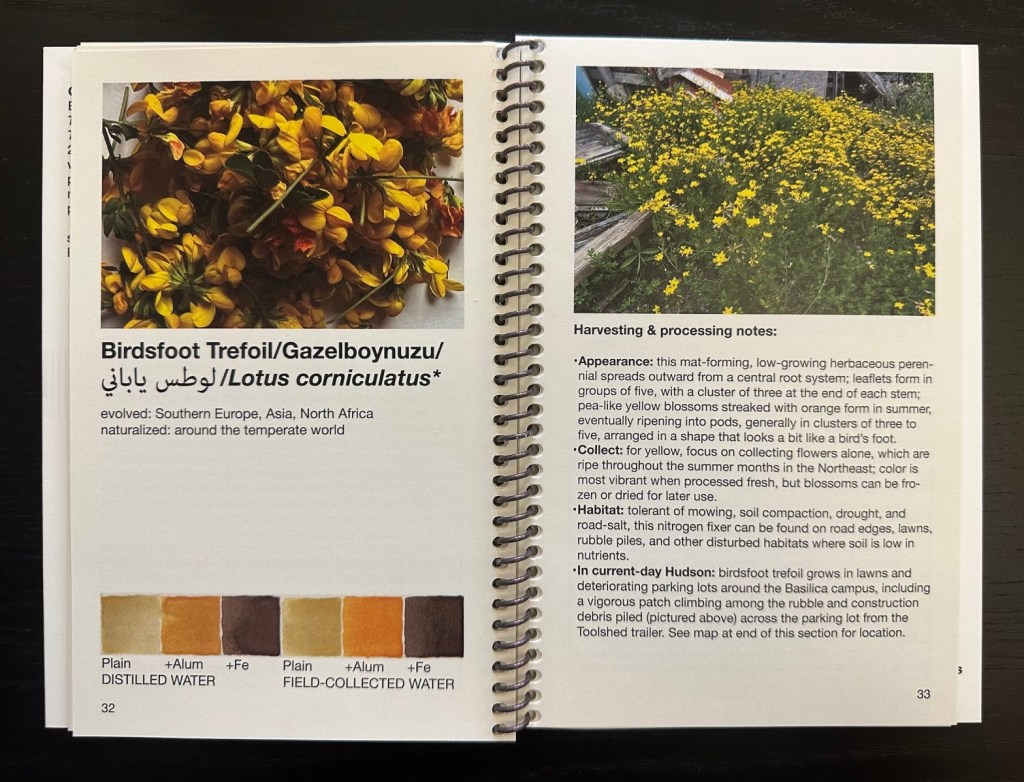

Photo: Lee Tesdell.

Behind farmer Lee Tesdell in the photo are rolled-up strips of prairie sod containing native plants that help improve his land’s resistance to climate change.

There are so many things we have taken for granted in our natural world. Consider weeds. We might have noticed that various flying things liked their blossoms, but we didn’t like them.

That is, until we started noticing that we wouldn’t have much food if those flying things didn’t pollinate plants.

Now some farmers who used to kill weeds are bringing them back. As Rachel Cramer reports at the Guardian, strips of native plants (weeds) on as little as 10% of farmland can reduce soil erosion by up to 95%.

“Between two corn fields in central Iowa,” she writes, “Lee Tesdell walks through a corridor of native prairie grasses and wildflowers. Crickets trill as dickcissels, small brown birds with yellow chests, pop out of the dewy ground cover. …

“This is a prairie strip. Ranging from 10-40 metres (30-120ft) in width, these bands of native perennials are placed strategically in a row-crop field, often in areas with low yields and high runoff. Tesdell has three on his farm.

“He points out several native plants – big bluestem, wild quinine, milkweed, common evening primrose – that came from a 70-species seed mix he planted here six years ago. These prairie plants help improve the soil while also protecting his more fertile fields from bursts of heavy rain and severe storms, which are becoming more frequent.

“ ‘To a conventional farmer, this looks like a weed patch with a few pretty flowers in it, and I admit it looks odd in the corn and soy landscape in central Iowa,’ … he said. ‘I’m trying to be more climate-change resilient on my farm.’ …

“Prairie strips also help reduce nutrient pollution, store excess carbon underground and provide critical habitat for pollinators and grassland birds. Thanks to federal funding through the USDA’s conservation reserve program, they’ve taken off in recent years.

“But the idea started two decades ago with Iowa State University researchers and Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge managers. Lisa Schulte Moore, a landscape ecologist and co-director of the Bioeconomy Institute at Iowa State University, who was integral to the research, knows that large patches of restored and reconstructed prairie are vital, especially for wildlife, but she argues that integrating small amounts of native habitat back into the two dominant ecosystems – corn and soya beans – can make a big difference. …

“In north-central Missouri, farmer Doug Doughty has been adding and expanding conservation practices, like no-till, for decades. He also has a few hundred acres of prairie enrolled in the USDA’s conservation reserve program. This past winter, he added prairie strips, as part of a plan to tackle nutrient pollution. High levels of nitrates and phosphorus can wreak havoc on aquatic habitats and the economies that depend on them. There are also health risks for people. Nitrates in drinking water have been associated with methaemoglobinaemia or ‘blue baby syndrome,’ and cancer. …

“During an outreach event in the Iowa Great Lakes region, Matt Helmers uses a rainfall simulator to demonstrate runoff and erosion with different conservation practices. He’s one of the prairie strips researchers and director of the Iowa Nutrient Research Center at Iowa State University. …

“During a big rain storm, each prairie strip in a field acts like a ‘mini speed-bump,’ said Helmers. A thick wall of stems and leaves slows down surface water, which reduces soil erosion and gives the ground more time to soak up water. Below ground, long roots anchor layers of soil while absorbing excess water, along with nitrates and phosphorus.

“Farmer Eric Hoien says he first heard about the conservation practice a decade ago, right around the time he was becoming more concerned about water issues in Iowa. But the final push to add 24 acres of prairie strips came from something Hoien saw in an plane above the Gulf of Mexico.

“ ‘I looked down and for what was probably 20 minutes, it was just like the biggest brown mud puddle I’d ever seen. And so I knew that, that stuff they say about the dead zone, from 30,000 ft, was real,’ Hoien said. …

“Hoien says prairie strips offer other benefits close to home. Neighbors often tell him they appreciate the wildflowers and hearing the ‘cackle’ of pheasants. He also enjoys hunting in the prairie strips and spotting insects he’s never seen before.

“The strips are hugely beneficial for pollinator populations, which have been dropping around the world. Researchers point to a combination of habitat loss, pesticide exposure, parasites and diseases, along with warmer temperatures and more severe weather events due to climate change.

“ ‘If we can help them have a place to live and something to eat, they can be better equipped to cope with those kinds of stress that they’re inevitably going to encounter in their environments,’ says Amy Toth, who is also part of the prairie strips research team and an entomology professor at Iowa State University. Research shows both the diversity of pollinator species and overall numbers are higher in prairie strips compared to field edges without native plants.

“And strips of native plants aren’t just good for pollinators. Researchers, including Schulte Moore, found a nearly threefold higher density of grassland birds on fields with prairie strips. She says that grassland birds have declined more than any other avian group in North America since 1970. …

“Schulte Moore says a group of forward-thinking, innovative farmers and partnerships with non-profits, foundations, universities and agencies in the midwest have helped prairie strips gain traction, but then a ‘monumental shift’ happened with the 2018 Farm Act, when prairie strips became an official practice in the federal conservation reserve program.” More here.

Pray that these federal conservation programs are not already slashed.

And for more on the prairie’s vast potential, read about Buffalo Commons, a movement launched by my husband’s classmate and his wife in the 1980s, here.