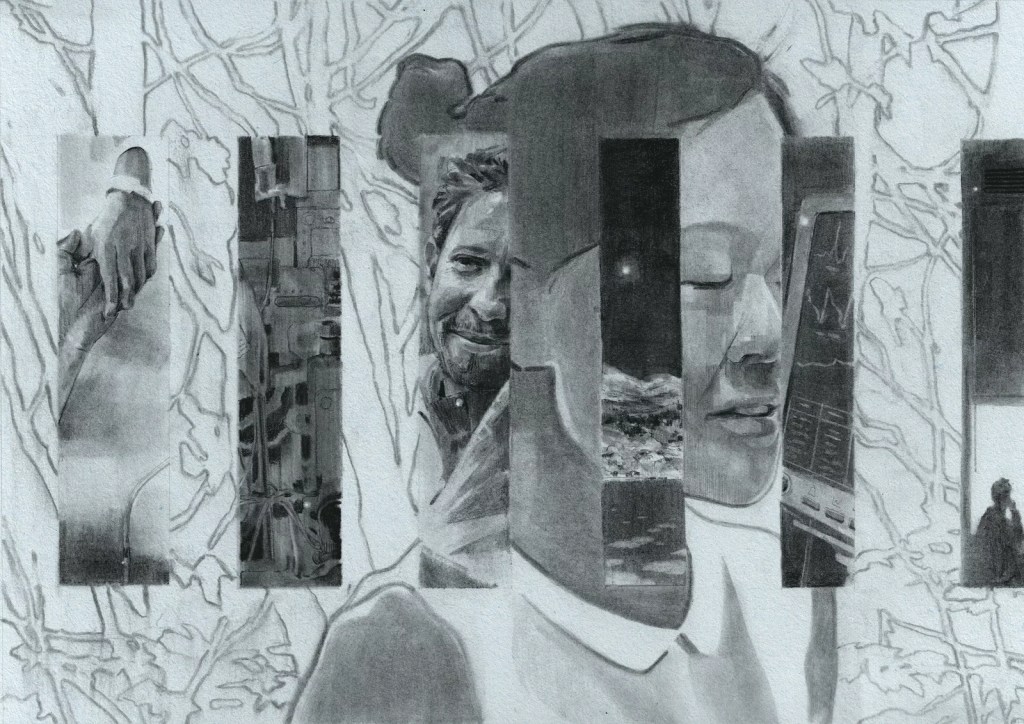

Photo: James Lee Chiahan/Procedure Press.

“Tone Shift,” by James Lee Chiahan. depicts musician Yoko Sen’s journey from being patient in the hospital to working to improve the sounds of ICU alarms around the world. Chiahan is a Taiwanese-Canadian artist currently working out of Montreal, Canada.

Those of us who have ever had a hospital stay know how difficult it is to get any sleep. Part of the reason is noise. Today’s article suggests that since artists started applying their creativity to the challenge, hospitals have new ways they could improve sounds and doctors have new ways to improve patient interactions.

Mara Gordon at NPR (National Public Radio) begins her story with Emily Peters, who had a rough time with the health care system when her daughter was born. “Peters, who works as a health care brand strategist, decided to work to fix some of what’s broken in the American health care system. Her approach is provocative: she believes art can be a tool to transform medicine.

“Medicine has a ‘creativity problem,’ she says, and too many people working in health care are resigned to the status quo, the dehumanizing bureaucracy. That’s why it’s time to call in the artists, she argues, the people with the skills to envision a radically better future.

“In her new book, Artists Remaking Medicine, Peters collaborated with artists, writers and musicians, including some doctors and public health professionals, to share [ideas] about how creativity might make health care more humane. …

“For example, the book profiles electronic musician and sound designer Yoko Sen, who has created new, gentler sounds for medical monitoring devices in the ICU, where patients are often subjected to endless, harsh beeping.

“It also features an avant-garde art collective called MSCHF (pronounced ‘mischief’). The group produced oil paintings made from medical bills, thousands and thousands of sheets of paper charging patients for things like blood draws and laxatives. They sold the paintings and raised over $73,000 to pay off three people’s medical bills.

“It’s similar to a recent performance art project not profiled in the book: A group of self-described ‘gutter-punk pagans, mostly queer dirt bags’ in Philadelphia burned a giant effigy of a medical billing statement and raised money to cancel $1.6 million in medical debt. …

“There’s very little in the way of policy prescription in this book, but that’s part of the point. The artists’ goal is to inject humanity and creativity into a field mired in apparently intractable systemic problems and plagued by financial toxicity. They turn to puppetry, painting, color theory, and music, seeking to start a much-needed dialogue that could spur deeper change.

“Mara Gordon: What made you want to create this book?

“Emily Peters: I think I’m always very curious why so many people – really the majority of everybody in any way involved in the health care system – feel so powerless. … And so the book came about as thinking about power and change. And then I realized that artists have this unique intersection where they are very powerful, they bring a lot of the things that were missing in health care, trying to build a better future.

“MG: What is it about art that feels like a tool to challenge that feeling of powerlessness?

“EP: The very first person I interviewed for the book was a photographer, Kathleen [Sheffer], who was a heart-lung transplant survivor. She used her camera in the hospital to try to be seen as more powerful, to be seen as a full person by these very fancy transplant surgeons who are whisking in and out of her room, viewing her as just a body. I saw that she had gained that power through being an artist.

“I had another conversation with a physician out of New York, Dr. [Stella] Safo. … She really highlighted that there’s this crisis of imagination. Everybody feels so demoralized that we can’t even imagine what we want to ask for to make it better.

“That’s a creativity problem. And the people who are creative are artists. They are really good at sitting in complexity and paradox, and not wanting everything to be perfect, but being able to imagine. And so that was the hypothesis: Oh, there’s something really interesting at this intersection between art and medicine. …

“MG: My favorite part of the book was the section where there’s a color palette, named for different medical phenomena: pill bottle orange, Viagra blue. … I think a lot of people in health care worry that too much color somehow distracts from the seriousness of medicine.

“EP: So many of these things, somebody chose, and they didn’t do a huge amount of research on it. They just chose it, and we take it as gospel now.

“The white coat ceremony. [I had thought it must have started in] medieval Florence: they were putting white coats on medical students and welcoming them into the guild, it just feels like this ancient tradition. And it’s something that was invented in Chicago in 1989. A professor was complaining that the students weren’t dressing professionally enough. …

“We surveyed a couple hundred people [and published the results online]: ‘What colors would you want to see in the hospital?’ I was expecting those soothing pastel tones. And it was totally different: it was neon purples and oranges and reds. Don’t assume what people want. We have the technology and the capability now to build in systems that give people some control and some agency over things like color. …

“MG: Has anyone told you that they think that health care is too important for art?

“EP: I’ve heard the criticism that this is just about wallpaper on a pig: ‘You’re talking about adding more sculpture gardens and increasing the cost of health care.’

“I did not want it to be a book about creating more luxurious hospitals. We have a crisis of financial toxicity, we have a crisis of outcomes. It’s specifically a book about fighting those things. …

“MG: Do you think medicine takes itself too seriously? Do we need more humor in health care?

“EP: You’re holding somebody’s heart in your hand – this is a very intense job. You’re trying to convince somebody to enter hospice – that is not easy. This is not an easy job. But that seriousness can feel almost like play acting and really inauthentic to people. …

“And that’s such a waste to me, because it is such a beautiful, incredible profession. We, as patients, also want you guys to be humans. We’re on your side.”

More at NPR, here. No paywall.

Oh I hope this goes somewhere!! I really liked the way Yoko Sen tried to pitch the various beepers in better keys.

>

Many of us know just why it’s needed.

I, too, hope this goes somewhere. Hospitals do save lives, but they certainly aren’t restful. Jangling, in fact.

Weirdly, I once almost dozed in one of those crashing MRIs. How could that be? I conclude that there is something kind of relaxing about being utterly unable to control the situation. Of course, it helps to know it will end soon!

The entire medical system needs more art and creative ways to heal people, doctors and facilities are so clinical, more empathy is needed!

I suppose there’s a need to protect yourself from caring too much, especially with heartbreaking lost causes, but a little empathy can go a long way.

No more blank cinder block walls! Glad artists are contributing to our health system,

I remember reading about the people-friendly design of Paul Farmer’s Partners in Health clinics around the world. I’m sure patients feel good in such places and believe they’ll get well.

I bet they get well faster and have better surgery outcomes 🙂