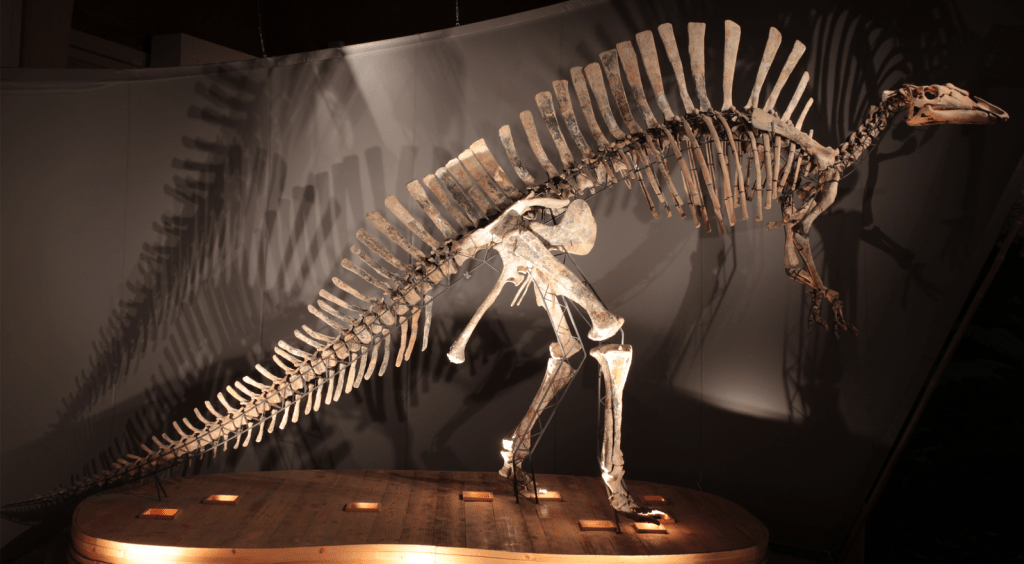

Photo: Filippo Bertozzo, Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia, Matteo Fabbri via Wikimedia Commons.

Ouranosaurus bones are among the many wonders found in Niger. For scale, the right femur is about a yard long.

Niger turns out to be a treasure trove for paleontology and archaeology, and as Nick Roll reports at the Christian Science Monitor, the country is working to develop enough local experts to deal with the riches. It’s not so farfetched in a place where nomads are already texting researchers about archaeological finds.

“Goats, cows, and pedestrians wander by the two unassuming shipping containers along a street in Niger’s riverside capital without a second thought. But inside lie nearly 50 tons of dinosaur bones wrapped in plaster – potentially some of the most significant paleontological finds this landlocked West African country, and even the continent, has ever known.

“There are fossils from perhaps as many as 100 different species, some of them from ancient animals never seen before.

“ ‘Small animals, mammals, flying reptiles, turtles’ as well as a 40-foot crocodile and ‘a dozen large dinosaurs that are new, including huge 60-footers, says American paleontologist Paul Sereno.

“Getting them to the capital was years in the making – and their journey isn’t over. The initial discoveries were made in 2018 and 2019, in the vast expanse of the Sahara Desert. It would take time and funding for a proper dig, though, so the paleontologists covered them up and buried them, hoping the winds wouldn’t expose them to curious nomads or dangerous smugglers.

“Then COVID-19 hit, shutting everything down until finally, last fall, Professor Sereno could return to unearth the fossils again.

“ ‘Niger is going to tell Africa’s story during the dinosaur era,’ he says. …

“The bones, soon to be shipped to Dr. Sereno’s lab at the University of Chicago for research, represent paleontology’s latest win against the harsh desert environment of Niger, which is home not only to fossils but also to soaring temperatures, shifting dunes, and various armed groups.

“But Chicago won’t be the bones’ final resting place. The fossils are earmarked to be eventually returned to Niger, where the kernels of a formal paleontology sector are being planted in a country that contains some of the richest paleontological finds in Africa but boasts no paleontologists of its own, or even academic programs dedicated to the field.

“ ‘Each time, we see that we find new dinosaurs, new fossils that permit us to say that the soil is rich – unlike other countries, and other continents,’ says Boubé Adamou, an archaeologist at the Institute for Research in Human Sciences who, as one of Niger’s foremost experts on excavations, helped lead this most recent expedition. …

“In a convoy speeding through the desert last fall, the team of about 20 found themselves massively outnumbered by scores of armed men riding in machine gun-mounted trucks. Those were just their guards, determined to keep this modern-day Saharan caravan safe from smugglers or bandits roving the dunes. …

“The team, composed of researchers and students from the United States, Niger, and Europe, went to three dig sites over three months. By the time they finished in December, they had unearthed everything from an Ouranosaurus with a 25-foot-long, bony ‘sail’ across the length of its back to the 6-foot thigh bone of a long-necked sauropod. …

“The vast expanses of Niger were [once] anything but dry, as rivers, wetlands, and lakes stretched across what researchers called the Green Sahara, home at one point to dinosaurs, and later, ancient human civilizations with embalming techniques that predate the Egyptians – relics of which were also found on the fall expedition. …

“It’s easy to see why Niger remains off the beaten path for paleontologists, despite its riches. As one of the poorest nations on Earth, it combines rough infrastructure with harsh desert conditions.

“But even if the Green Sahara is a thing of the past, the desert today is anything but desolate. Local nomads who’ve long mastered the difficult terrain have become key to conducting paleontology there, spotting bones and leading expeditions through otherwise unnavigable desert expanses. While the pandemic held Dr. Sereno’s team at bay, nomads kept a watchful eye on the carefully buried treasures, texting him updates. …

“Niger Heritage is a project drawn up by Dr. Sereno, Mr. Adamou, and coterie of international and Nigerien researchers and government officials. It envisions two museums [with] the capacity to not just display the fossils but also, for the first time, conduct homegrown research. …

“Niger’s first paleontologists, it is hoped, might be in undergraduate courses right now. With the right guidance and funding – to do Ph.D. programs outside the country – they could start correcting the lopsided nature of paleontology, where resources and opportunities are concentrated in rich countries.”

More at the Monitor, here. No firewall. Subscriptions encouraged.