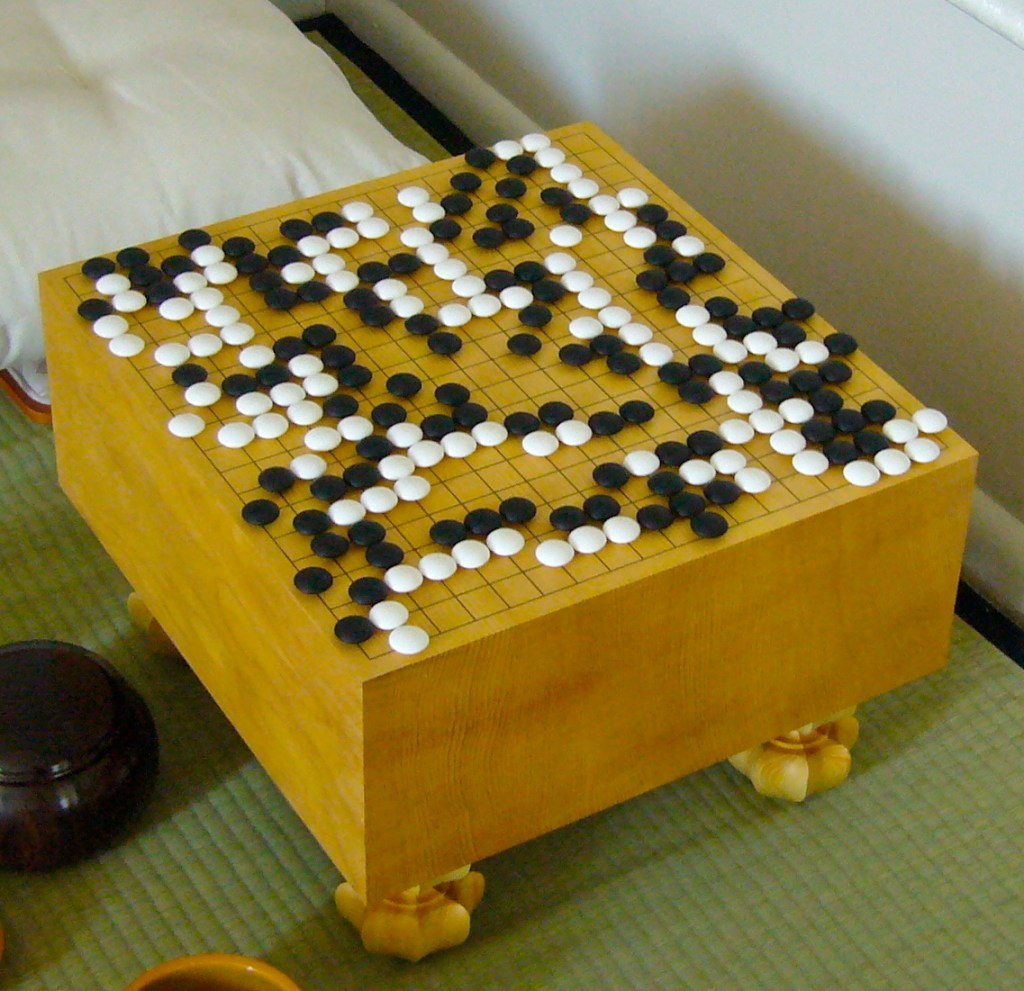

The Chinese game called Go is more than 2,500 years old.

This past summer, I blogged about a new board game called Wingspan. It sounded wonderful, especially for bird lovers, like those in my family. I bought it.

Well, I think it is going to be wonderful, but the rules are really hard. Recommended for people over 14, it is still too “buch for be, “as Rudyard Kipling’s Elephant’s Child says.

Fortunately, it’s not too much for my 9-year-old grandson, who is gradually figuring it out and explaining it. Otherwise, I might have had to call on artificial intelligence experts, like those described in today’s story.

Samantha HuiQi Yow explains at Wired: “In 1901, on an excavation trip to Crete, British archaeologist Arthur Evans unearthed items he believed belonged to a royal game dating back millennia: a board fashioned out of ivory, gold, silver, and rock crystals, and four conical pieces nearby, assumed to be the tokens. Playing it, however, stumped Evans, and many others after him who took a stab at it. There was no rulebook, no hints, and no other copies have ever been found. Games need instructions for players to follow. Without any, the Greek board’s function remained unresolved—that is, until recently.

“Enter artificial intelligence and a group of researchers from Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Thanks to an algorithm the team used to analyze the playability of one suggested ruleset, the century-old guesswork could soon be taken out of the Knossos game. Today, not only can its recognition as a game be further assessed, with hopes of a clearer answer in future, a version of it is also playable online. And for the first time, so are hundreds of other games thought to have been lost to history.

“Board games go back a long way. Centuries ago, before the chess we know today, there was Chaturanga in India, Shogi in Japan, and Xiangqi in China. And long before them was Senet, one of the earliest known games, which, along with others played in ancient Egypt, may have ultimately inspired backgammon. ‘Games are social lubricants,’ explains Cameron Browne, a computer scientist at the university who received his PhD in AI and game design. ‘Even if two cultures don’t speak the same language, they can exchange play. This happened throughout history. Wherever people spread to, wherever soldiers were stationed, wherever merchants were trading. Anyone who had time to kill would often teach those around them the games they knew.’ …

“[But] the rules were typically passed on by word of mouth instead of being written down. The little that is known is left open to modern interpretation.

“It’s these lapses in board game history that gave legs to the five-year Digital Ludeme Project, which Browne leads. ‘Games are a great cultural resource that’s been largely underutilized. We don’t even know how so many of them were played, especially when you go farther back in time,’ he says. ‘So the question for me was, can we use modern AI techniques to shed insight into how these ancient games were played and, together with the evidence available, help reconstruct them?’

“As it turns out, the answer is a resounding yes. It’s been three years since Browne and his colleagues set to work, and already they have brought nearly a thousand board games online, ranging from across three time periods and nine regions. Thanks to them, games once popular in the second and first millennia BC, like 58 holes, are now just a few clicks away for anyone on the internet.

“Interestingly enough, this reconstruction process begins with the opposite. Games are first broken down into fundamental units of information called ludemes, which refers to elements of play such as the number of players, movement of pieces, or criteria to win. Once a game is codified in this manner, the team then fills in the missing pages of its rulebook with the help of relevant historical information, like when it or another game with similar ludemes was played and by whom.

“The riddle however is only partly solved at this stage. Others who do similar work–manually–usually hit a dead end here. It’s because what looks good on paper might not translate as well in reality, Browne explains. ‘The rules might make sense when you read them, but you don’t know how well they actually work unless you play the game. Quite often, rules that make perfect sense play terribly as games.’ …

“But computers can have blind spots too, in that they only measure what’s measurable. Here’s where Walter Crist comes in.” More at Wired, here.