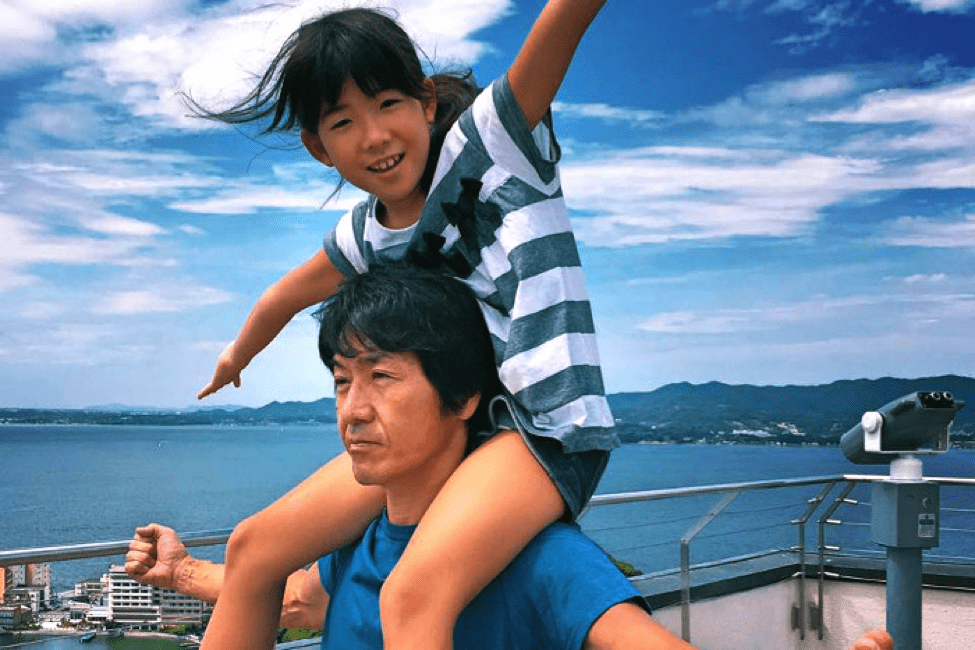

Photo: Ken Yoshida at CarterJMRN.

Gen Z Japanese men are leading a cultural change that the government is fully supporting.

When my husband worked in Rochester, New York, we knew several coupes from Fuji Xerox who settled there for a period of years. I remember the laughs my friend Yuriko had over the effects of a different culture on Japanese men. She couldn’t get over the memory of a Japanese husband in a laundromat doing his own laundry. That would not happen at home in the 1970s.

Other cultural changes have been taking place since then.

Patrick Winn reported at Public Radio International’s The World about fatherhood in Japan, where traditionally, dads were not engaged with the daily lives of their children.

Winn writes, “Yuko Kuroda and her husband, Takashi Kuroda, live in a modest, two-story home in Tokyo’s outskirts. Both in their early 40s, Yuko Kuroda works at a daycare center, while Takashi Kuroda has a white-collar job. …

“In contemporary Japan, roughly one-third of women under the age of 50 do not have children. Couples who choose to raise kids usually stop at one. …

“Takashi Kuroda, his face streaked with black marker, just emerged from a rolling-on-the-floor play session with his son and daughter, aged 3 and 6, on a Sunday afternoon. The children drew whiskers on his cheeks while shouting, ‘Neko! Neko!’ (Japanese for ‘cat’).

“ ‘I really recommend this lifestyle,’ he said. ‘Raising five kids is fun.’ …

“Officials warn that if the birth rate doesn’t rise, Japan could become unrecognizable in decades to come: less affluent, less vibrant and less powerful.

“What currently is deterring couples from raising children is being associated with overwork and sky-high housing prices.

“But one of the major factors concerns dads ‘doing too little around the house,’ according to Mary Brinton, a Harvard University sociologist who has studied Japanese demographics for decades and has even advised Japanese officials.

“Traditionally, when Japanese couples have children, ‘women do most the housework and child care,’ Brinton said, and for working moms, the idea of holding down what is essentially a second, unpaid full-time job is ‘not very attractive.’ …

“Among the world’s high-income countries, including the US, fathers average more than two hours of daily housework and child care. In Japan, the average is only about 40 minutes.

“But what erased Yuko Kuroda’s reluctance in raising five kids was that Takashi Kuroda wasn’t afraid to wipe a butt or wash a dish.

“ ‘If one of the kids falls ill, he’ll immediately ask for a day off from work,’ she said. …

“Takashi Kuroda believes raising Japan’s birth rate requires a revolution in fatherhood. More than a decade ago, the government launched a social engineering campaign urging fathers to become ikumen, a Japanese word that loosely translates to ‘super dads.’

“Through public service announcements, namely posters, websites and online videos, Japan promoted this ideal of fatherhood. The ikumen eagerly burp babies, change diapers and walk toddlers to the park. …

“Fathering Japan, a nonprofit organization, contracted with the government to promote an ‘ikumen boom’ and teach fathers, through in-person classes, how to care for kids and do chores.

“Manabu Tsukagoshi, a director with the group, believes it has successfully shifted fathers’ mindsets across Japan. But workplace culture is much harder to change.

“Plenty of dads now want to live as ikumen, Tsukagoshi said, but — especially in white-collar jobs — they might toil for old-fashioned bosses who pressure workers to stay late and, after hours, bond over beer and sake.

“Japan’s paternity-leave policies are now among the best in the world, but too many fathers fear taking time off work and risking the disapproval of their bosses or colleagues.

“ ‘I’m actually a bit ashamed of our Japanese men,’ Tsukagoshi said. ‘As employees, we have rights, but men hesitate to break from the norm. If other guys in the office aren’t taking paternity leave, they won’t feel keen to be the first.’

“But Takashi Kuroda is hopeful. He believes the revolution in fatherhood — in which dads stand up to corporations and put family first — is on the horizon.

“Fifteen years ago, the rate of fathers taking paternity leave was almost zero. Only in recent years, it’s edged up to roughly 15% while by the decade’s end, Japan’s government hopes to up the rate to 85%.

“[Takashi Kuroda] credits Gen Z fathers for helping redefine what it means to be an attentive dad, unlike their own fathers, who often stuck with a corporation their entire working lives.

“ ‘Younger Japanese dads don’t feel like they have to belong to one company. So, they’re not so terrified of their bosses … and will stand up for themselves,’ he said.

“The COVID-19 pandemic, which saw more parents working at home, spurred a higher number of fathers to refocus on family, Takashi Kuroda said. He’s among the fathers who not only demanded paternity leave but took an entire year off for his third child, also insisting on remote work. …

“By late afternoon, Yuko Kuroda read to her children from a storybook while Takashi Kuroda was in the kitchen, elbows deep in dirty dishes. The sink was full of bowls used for breakfast, and water-logged noodles swirled around the drain. He looked silly — the cat whiskers remaining on his face — as he radiated joy.

“ ‘I’m very, very, very happy,’ he said.

“When asked if he’d be happy to have a sixth child, he answered maybe, as Yuko Kuroda popped in to end the questioning.

“ ‘No way,’ she said. ‘Our car only seats seven people. This is it.’ ”

More at The World, here. Lovely pictures. No firewall.