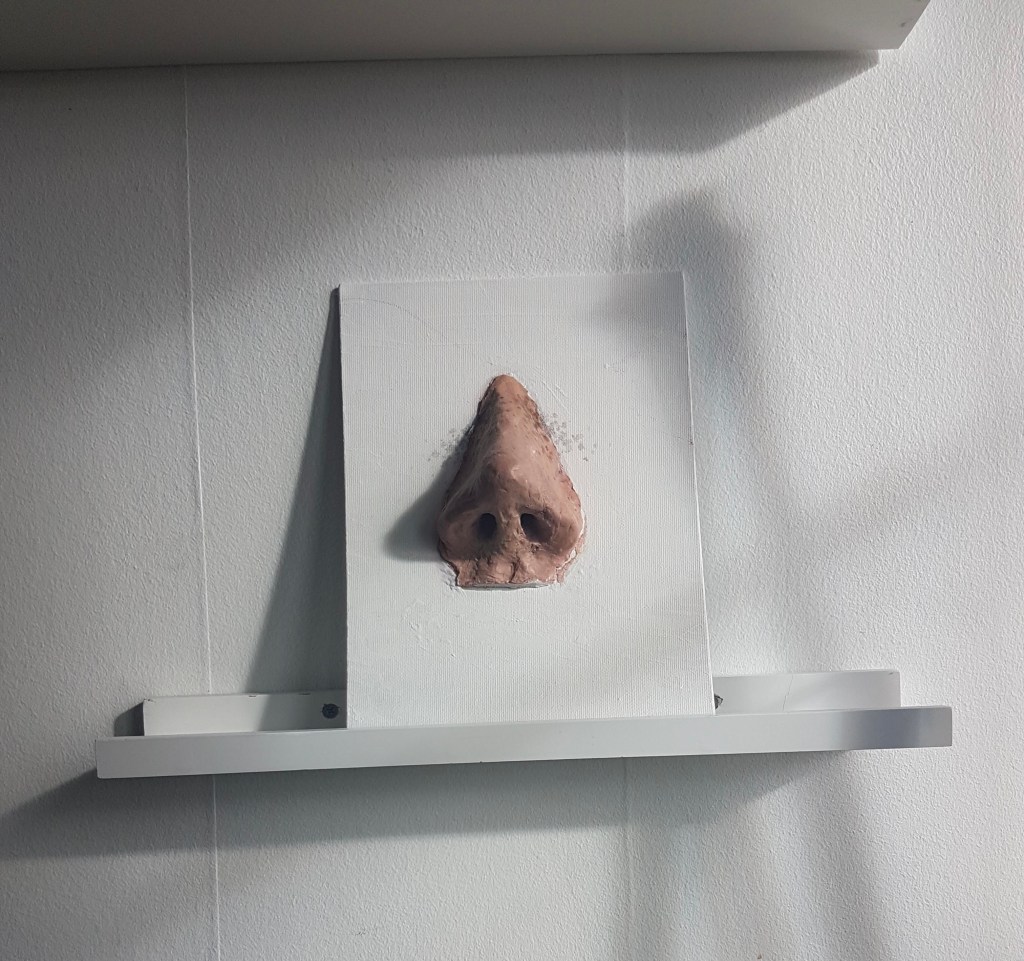

Photo: DCPhoto/Alamy.

In Sweden, over-55s can study at Senioruniversitetet for a relatively low fee.

An aunt and uncle on my father’s side were always voracious for education, and when they retired, they took learning vacations with Elderhostel [now called Road Scholar]. More recently, two different friends of mine enjoyed hearing Road Scholar’s academic lecturers on a trip to the Panama Canal, although my sense is that the excursions are heavier on things like indigenous dance performances than they used to be.

Miranda Bryant reports at the Guardian that in Sweden, seniors are teaching one another rather than hiring outside professionals. Reader Stuga4, for example, helped to teach a class on a recent Nobel economics prize winner.

Bryant writes, “record numbers of retirees are enrolling in a university run ‘by pensioners for pensioners’ amid increased loneliness and a growing appetite for learning and in-person interactions.

“Senioruniversitet, a national university that collaborates with Sweden’s adult education institution Folkuniversitetet, has about 30 independent branches around the country which run study circles, lecture series and university courses in subjects including languages, politics, medicine and architecture.

“The Stockholm branch, which is Sweden’s largest, has become so popular since it was founded in 1991 that it is now run across multiple venues across the capital by about 100 volunteers. Its most popular event, the Tuesday lectures, gets about 1,000 people each week.

“Recent Stockholm lectures have included ‘The art of awarding Nobel prizes’ by a former member of a Nobel committee, ‘Disinformation and AI – the threat we invented ourselves’ and ‘From soap to cultural heritage/canon and vice versa.’

“Inga Sanner, chair of Senioruniversitetet in Stockholm, said membership nationally was at an all-time high. … In 2023 there were 2,099 events held across Sweden attended by 161,932 participants, according to Folkuniversitetet. This year, that number is projected to increase to 177,024 participants across 2,391 events.

“Gunnar Danielsson, secretary general of Folkuniversitetet, said: ‘The desire to learn for pleasure’s sake, or for the sake of learning as such, is a joy to experience in a society which is increasingly obsessed with learning and education as [only] preparation for work.’

“Sanner, a retired history professor, said older people were ‘more and more alert’ and that there is a ‘fantastic hunger for education.’ She added: …

“The wider societal role that Senioruniversitetet plays is becoming increasingly important, she said, and the learning and wellbeing of its members has a knock-on effect to their families and beyond. …

“For many of their volunteers, their office in central Stockholm is like a workplace. ‘It is very meaningful work, but also you have such a lovely time and meet others.’ Sanner said the demographic of its membership does, however, tend to be ‘too homogenous,’ adding that they need to do more to extend their reach to a more diverse audience.

“Susanne Abelin, 66, a former journalist from Norrtälje, near Stockholm, volunteers on the university’s newsletter and is learning Italian. Ageism is rife in Sweden, she said, and palpable in day-to-day life. ‘You are seen more or less as an idiot.’ … But Senioruniversitetet, where over-55s can learn for a relatively low fee, is ‘a bit of the Swedish welfare system that is still left.’ …

“Joachim Forsgren, 71, a former physician who now volunteers for the Stockholm branch, has given lectures on ‘man and drugs’ and tuberculosis. …

“By volunteering, he said, ‘we are contributing to some kind of democracy project. This is really trying, especially in this day and age, to get people interested in what is going on.’ Amid the rise of online disinformation and populism, the university helps people to ‘look critically at the amount of information we are almost drowning in every day.’ “

There’s a Harvard-affiliated program like the one in Sweden, with retirees teaching courses in their field. My understanding from friends who have participated is that it’s quite demanding, for both the teacher and the student. More at the Guardian, here.