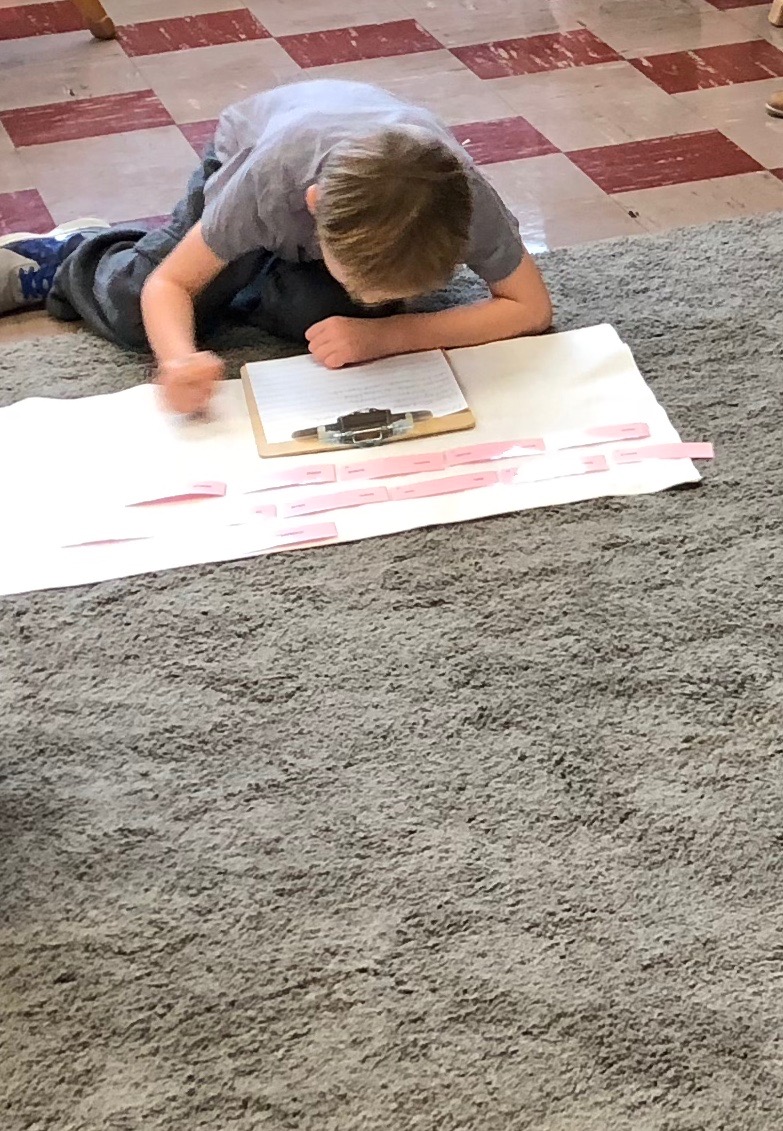

Photo: Ann Scott Tyson/Christian Science Monitor.

This photo from 1992 shows Bai Guiling teaching multi-grade primary students in a cave classroom carved from a hillside in the village of Yangjiagou. It had no electricity and few books.

Today’s story is about two women who transformed education in rural China. It’s written by Ann Scott Tyson of the Christian Science Monitor, who wanted to follow up on an article she wrote 30 years ago.

“After a 12-hour train ride, I’ve reached a remote village on China’s Loess Plateau, where I’m searching for a teacher I wrote about 30 years ago. I can still picture Bai Guiling juggling lessons for four grades in a dim cave classroom carved from the yellow earth. Her dedication to the needy village children was unforgettable. Now, I want to revisit her story as a window into education in rural China today.

“But no one in the dusty hamlet in northern Shaanxi province has heard of Teacher Bai or even remembers the school. … I flip through my notebook looking for the phone number of the only person who might be able to help – a Chinese American woman who years ago took a special interest in Teacher Bai.

“Sitting in my taxi while the police watch from down the road, I tap her U.S. number into my phone and wait for what seems like forever.

“ ‘Hello?’ a frail but chipper voice answers. It’s Lin-yi Wu.

“A few days earlier, in mid-May, I’d tracked down Ms. Wu, a retired librarian, at a senior living home in Walnut Creek, California. The nonagenarian was recovering from a fall – taken while jazz dancing – but was in good spirits. …

“Born the daughter of a well-to-do Shanghai antiques merchant in 1933, Ms. Wu received an elite education that bore no resemblance to Teacher Bai’s bare-bones cave classes. She rode rickshaws to a stately Shanghai middle school run by American missionaries. After graduating from the top-flight Peking University, she was retained to teach French. A formative moment came when Communist Party authorities exiled her and her husband-to-be, English professor Hung-sen Wu, to labor in a hardscrabble mountain village outside Beijing in 1958, during Mao Zedong’s commune movement.

“ ‘My eyes were opened to see how the majority of Chinese lived,’ Ms. Wu told me. For that, she was grateful. But she also witnessed how Mao’s failed communes slashed farm output, leaving bok choy wilting in the fields and piglets dying in the street. A massive famine ensued, forcing villagers to eat leaves and corncobs. ‘It was horrible,’ she said. From 1959 to 1961, tens of millions of Chinese starved.

“Once back at Peking University, Ms. Wu was shocked when authorities spread propaganda about a bumper harvest, rejoicing with music and gongs. ‘People are dying, and they celebrate the big harvest? That was the last straw,’ she said. ‘I could never live under a government that tells such a lie to the detriment of its people.’ In 1961, the couple fled via Hong Kong to the United States. …

“Forging a life in America, the Wus never lost the desire to help their destitute countrymen. Then, in April 1992, they opened the Christian Science Monitor and read my article about Teacher Bai’s struggles. At once, they each decided – without a word between them – to use their savings to build the village a proper school. … She penned a letter to me in Beijing, asking to contact Teacher Bai.

“But where is Teacher Bai now? I ask over the phone. ‘I don’t know where she lives, but I remember her village was in Ansai County,’ Ms. Wu tells me. ‘And I have her daughter’s phone number.’

“I open my road atlas and scour the map of Ansai, two counties away from where I am. Suddenly it makes sense – there are two villages with the same name, Yangjiagou, and I’m in the wrong one.

“Her smile and warmth are infectious. After 30 years, I instantly recognize Teacher Bai when I see her waiting for me at the train station in the nearby city of Yan’an, a meeting arranged by her daughter. It feels like we never lost a beat. Driving a borrowed car, she whisks me into the rugged countryside. …

“ ‘Look at this old classroom!’ she says, peering through the worn wooden lattice of the cave’s front window at the peeling mud-and-straw walls. ‘I taught here for five years. We were so poor,’ she says. …

“Born in 1964 to a farming couple in a cave high on a barren hillside a few miles away, Ms. Bai was the eldest of five children – four girls and a boy. Food was scarce in the wake of China’s famine. They ate boiled thistles and cornhusk buns. ‘That counted as good food,’ she says. …

“ ‘I want to popularize the importance of primary education,’ she told me back in 1992. … Her dream: to rally the villagers to build a new school. …

” ‘The article you wrote changed my fate, and the fate of three generations of my family.’

“Not long after my 1992 trip, a local official came to find Teacher Bai. Breathlessly, he told her a group of overseas Chinese and Americans wanted to build a new primary school at Yangjiagou – and they named her to be in charge. …

“Back in the U.S., Ms. Wu excitedly tallied the funds. After a benefit dinner, greeting card drive, and garage sale – combined with her $4,000 in savings – she’d amassed more than $8,000 as of 1994. It was enough to build Yangjiagou a new school, the first by her new organization, Friends of Rural China Education (FORCE). …

“Through a Catholic church with contacts in Hong Kong, she found a nun who would soon travel to mainland China to teach. They arranged for the nun to hand-deliver $8,000 in cash to Teacher Bai at the train station in Guangzhou, across the border from Hong Kong. ‘I will never forget what Teacher Bai told me,’ recalls Ms. Wu. ‘She said, “I will guard this money with my life.” ‘ “

It’s actually a very long article, but how can I not love it? Read the whole beautiful thing at the Monitor, here. No firewall.