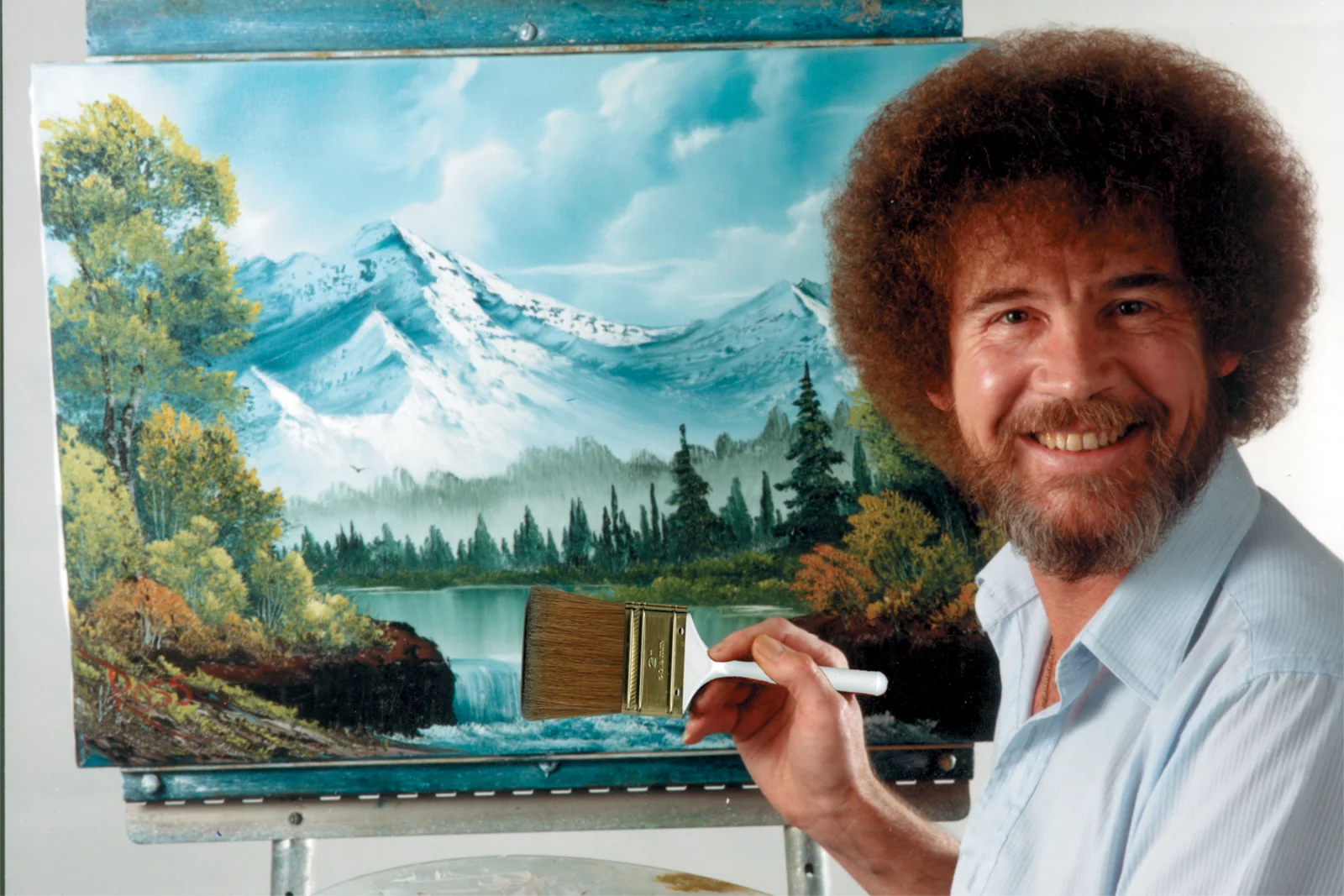

Photo: Bob Ross Inc./AP.

The late Bob Ross encouraged millions of Americans to make and appreciate art through his show The Joy of Painting, which has aired on PBS stations since 1983.

I once got an art kit from public broadcasting painter Bob Ross for my older granddaughter, a big fan. She was happy with the kit, but she did admit later that Ross made everything look easier on television than it really was.

Now we know that many other people not only liked Ross’s art, but want to support the medium where it was presented.

Rachel Treisman writes at National Public Radio (NPR), “The first of 30 Bob Ross paintings — many of them created live on the PBS series that made him a household name — have been auctioned off to support public television.

“Ross, with his distinctive afro, soothing voice and sunny outlook, empowered millions of viewers to make and appreciate art through his show The Joy of Painting. More than 400 half-hour episodes aired on PBS (and eventually the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) from 1983 to 1994, the year before Ross died of cancer at age 52. …

“His show still airs on PBS and streams on platforms like Hulu and Twitch. It has surged in popularity in recent years, particularly as viewers searched for comfort during COVID-19 lockdowns. … But his artwork rarely goes up for sale — until recently.

“In October, the nonprofit syndicator American Public Television (APT) announced it would auction off 30 of Ross’ paintings to raise money for public broadcasters hit by federal funding cuts. It pledged to direct 100% of its net sales proceeds to APT and PBS stations nationwide. Auction house Bonhams is calling it the ‘largest single offering of Bob Ross original works ever brought to market.’ …

“The first three paintings sold in Los Angeles on Nov. 11. for a record-shattering $662,000. Bonhams says the works attracted hundreds of registrations, more than twice the usual number for that type of sale. …

“Said Robin Starr, the general manager of Bonhams Skinner, the auction house’s Massachusetts branch, ‘These successes provide a solid foundation as we look ahead to 2026 and prepare to present the next group of Bob Ross works.’

“The next trio of paintings will be auctioned in Massachusetts in late January. The rest will be sold throughout 2026 at Bonham’s salesrooms in Los Angeles, New York and Boston. …

“Congress voted in July to claw back $1.1 billion in previously allocated funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), leaving the country’s roughly 330 PBS and 244 NPR stations in a precarious position.

“CPB began shutting down at the end of September … and several local TV and radio stations have also announced layoffs and closures.

” ‘I think he would be very disappointed’ about the CPB cuts, [Joan Kowalski, president of Bob Ross, Inc.] said of Ross. … I think this would have probably been his idea.” Kowalski, whose parents founded Bob Ross Inc. together with the painter in 1985, said Ross favored positive activism over destructive or empty rhetoric. …

“The Ross auction aims to help stations pay their licensing fees to the national TV channel Create, which in turn allows them to air popular public television programs. … Bonhams says the auction proceeds will help stations — particularly smaller and rural ones — defray the cost burden of licensing fees, making Create available to more of them. …

“The 30 paintings going up for sale span Ross’ career … include vibrant landscapes, with the serene mountains, lake views and ‘happy trees’ that became his trademark.

“Ross started painting during his 20-year career in the Air Force, much of which was spent in Alaska. That experience shaped his penchant for landscapes and ability to work quickly — and, he later said, his desire not to raise his voice once out of the service.

“Once on the airwaves, Ross’ soft-spoken guidance and gentle demeanor won over millions of viewers. His advice applied to art as well as life: Mistakes are just ‘happy accidents, talent is a ‘pursued interest,’ and it’s important to ‘take a step back and look.’ …

“In August [before any talk of a public television fundraiser] Bonhams sold two of Ross’ early 1990s mountain and lake scenes as part of an online auction of American art. They fetched $114,800 and $95,750, surpassing expectations and setting a new auction world record for Ross at the time. Kowalski says that’s when her gears started turning.

” ‘And it just got me to thinking, that’s a substantial amount of money,’ she recalled. ‘And what if, what if, what if?’ “

More at NPR, here. A few days ago funder CPB announced it was shutting down. But, by hook or by crook, public tv will carry on.