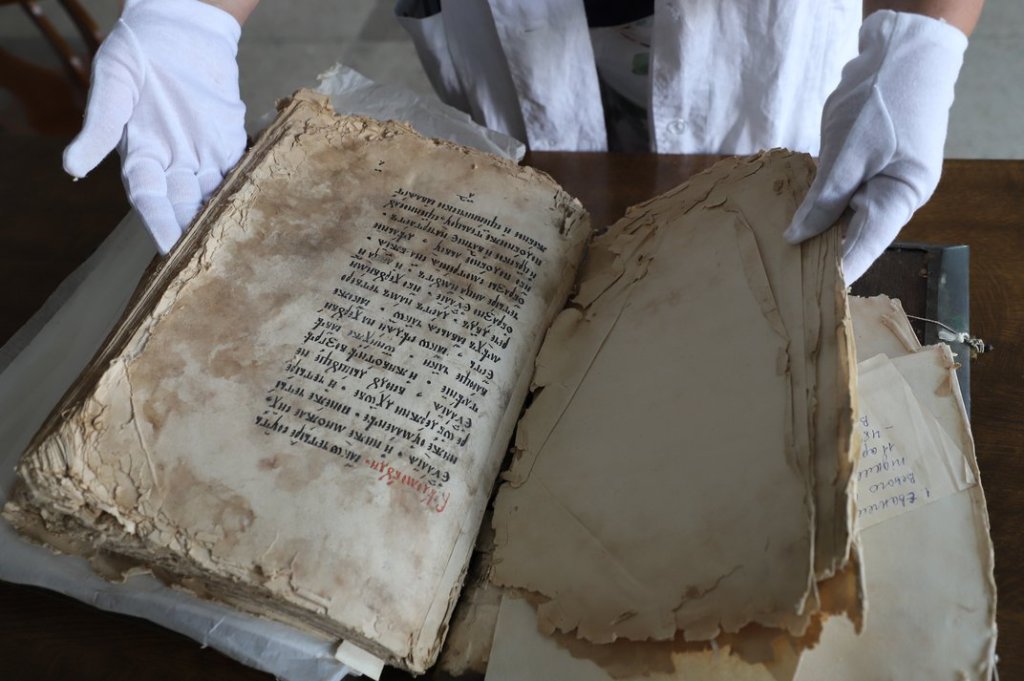

Photo: Navajo-Hopi News.

Two Gray Hills Skatepark in Newcomb, New Mexico.

The forced assimilation of indigenous children into colonist culture damaged the children, the relatives of the children, and the grown children’s descendants. In today’s story, we learn how one descendant was surprised to discover she was Navajo and looked for a way to help her long-lost community.

Roman Stubbs writes at the Washington Post, “The wind rolled off the Chuska Mountains and along the desert floor, whipping red dust and tumbleweed across the pavement of Two Grey Hills Skatepark. It was a pale Sunday morning in May, and Amy Denet Deal stood on a ledge, tying a crimson bandanna around her silver braids and smiling as she watched the children swerve down ramps in the middle of the storm.

“ ‘Amy!’ ” a young boy yelled, excited to greet the woman who helped bring the skatepark to this remote northwest corner of the Navajo Nation.

“ ‘Hi, honey. How you doing?’ she replied. ‘You’ve grown a foot since I last saw you!’

“Denet Deal, 59, considered herself younger than the boy in Diné (Navajo) years. She had reconnected with the tribe only five years earlier after a lifetime of displacement, giving up most of her belongings and a lofty salary as a corporate sports fashion executive in Los Angeles to move to New Mexico.

“The pandemic opened her eyes to the inequities children on the reservation face, including high rates of diabetes, mental health issues and suicide. Navajo Nation is roughly the size of West Virginia — 16 million acres stretching across Arizona, New Mexico and Utah — yet there are few opportunities for kids to play sports, with many remote areas lacking outdoor recreation and athletic facilities.

“She searched for solutions to give back and finally landed on one: Why not a skatepark?

“It took years of fundraising, with plenty of setbacks, but more than a year after it opened, she could still point to the benefits the park was bringing to her community. The kids from a nearby housing project came for free clinics held every weekend. Parents and grandparents parked their trucks near the concrete to watch, sharing food with one another in their camping chairs as the breeze stung their faces.

‘If I talk to any skateboarder, the first thing they’ll always tell me is, “Skateboarding saved my life,” ‘ Denet Deal said. …

“And so here she was again, making the four-hour drive from Sante Fe to her ancestral homeland, because visits were also helping her with the trauma of her past.

“ ‘The plus side of this is I come from displacement and a strange start in the world,’ Denet Deal said. ‘It’s really helping me heal through that work.’

“Denet Deal didn’t visit the Navajo Nation until she was in her late 30s. Her mother, Joanne, had been forced into a boarding school in Farmington, N.M., in the early 1950s. Joanne’s family had no horse or car to visit her for years. ‘She suffered all kinds of abuse and forced assimilation,’ Denet Deal said.

“Through the government’s Indian Relocation Act, Joanne left the reservation with a one-way bus ticket to Cleveland in her late teens. She got pregnant with Amy. Like thousands of other Native children in the 1960s, Amy was placed into adoption and taken in by a Catholic charity. …

“ ‘I was put up for adoption without anybody contacting my birth family, no connection to the tribe,’ Denet Deal said. ‘I grew up completely displaced from my community. I was the only Brown person in rural Indiana.’ …

“She found something to hold on to when she learned how to use a sewing machine as a child. She started making all of her own clothes and threw herself into fashion. Denet Deal developed into a rising star in the active sportswear space in the early 1990s; at 26, she was creating apparel at Reebok and by 30 she took over as design director at Puma. …

“For years, she searched for her mother. She hired a private investigator and scoured the internet. She numbed the emptiness with alcohol and work.

“In 1998, she had a breakthrough. Denet Deal convinced the Indiana Department of Health to release her record of adoption and was given Joanne’s address and phone number. She wrote Joanne a letter and received a letter back. Denet Deal visited her mother for the first time in Ohio, and together they eventually traveled to the Navajo Nation to meet other family.

“ ‘It wasn’t warm and fuzzy,’ she said. … ‘It brought back a lot of things for my mom that were hard.’ …

“Some locals rejected her because she didn’t grow up in the Navajo Nation. She was still getting to know many of her family members, and her presence could trigger reminders of a painful history for them. …

“The pandemic offered Denet Deal a chance to give back what she learned in another life. She used her past skills as a wealth generator for major corporations to help raise more than $1 million in medical supplies, food and support for a domestic violence shelter. But she wanted to do more, having seen up close the problems for children on the reservation.

“ ‘I just thought a skatepark was a really great thing to have for them.’ “

At the Post, here, you can read about the people who helped make it happen.