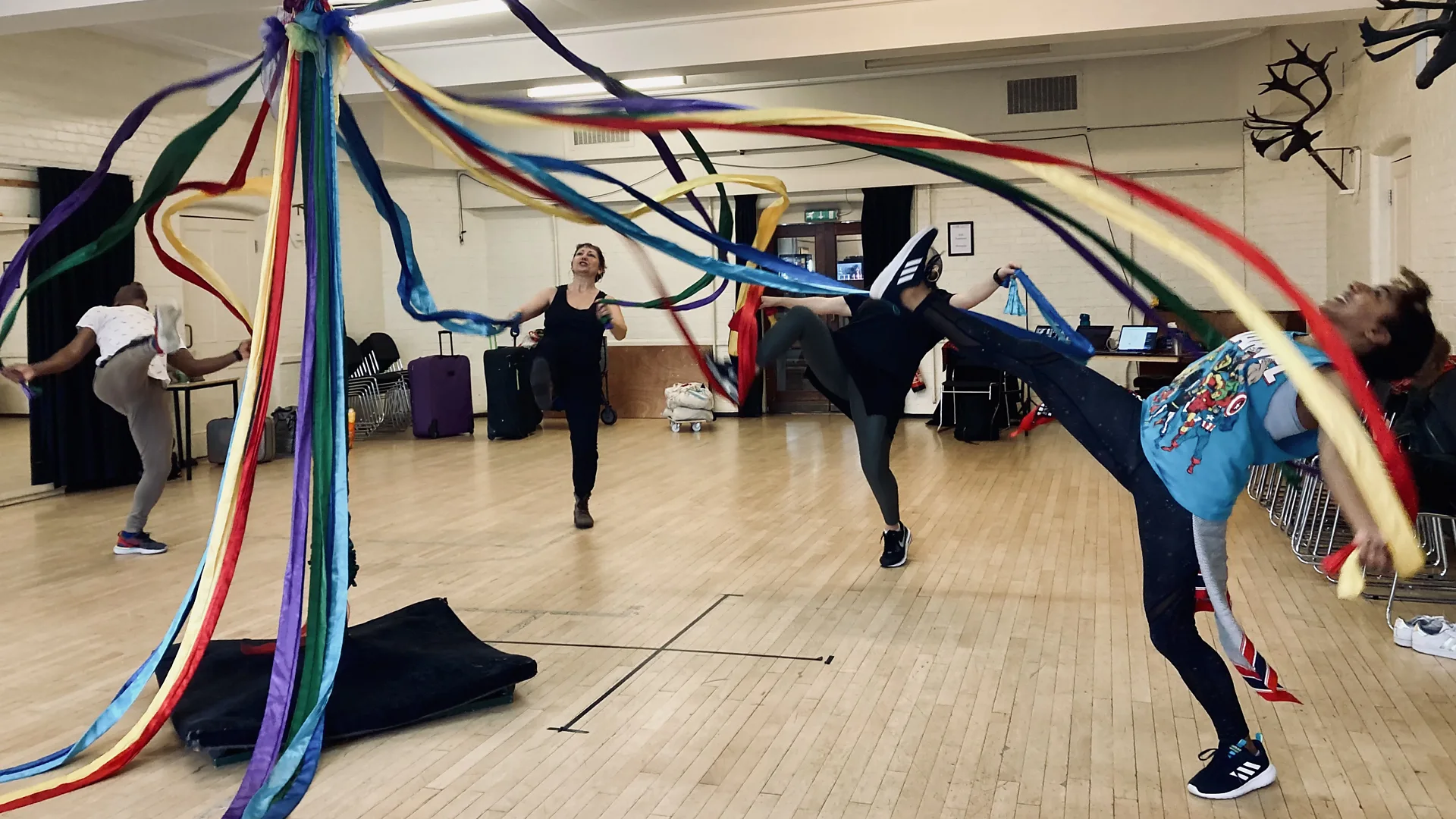

Photo: Zoey Goto.

UK’s Folk Dance Remixed combines traditions like May Day music with contemporary street dance styles.

On May Day, I was telling Diana that I had just received a surprise May Basket from my college’s local club. I have left May baskets of my own off and on since childhood, loving people’s puzzlement. Now it was time for me to wonder who I should thank.

That reminded Diana that for years she went to New York City’s Riverside Park on numerous May firsts to see the Morris dancers perform.

Nowadays, May 1 is associated with the international labor movement, and that’s a fine thing, too. But I am usually conscious of a different, more ancient celebration underneath it all.

Today’s story is about reimagining traditions like the Morris dancing of May Day for a new age.

Zoey Goto wrote at the BBC, “Camden’s Cecil Sharp House has been questioning the very notion of what traditional British music means in the multicultural 21st Century.

” ‘Hip-hop is the folk dance of today,’ said Natasha Khamjani, breathing heavily. They’re both social dances created for crowd participation, both also existing on the fringes of the mainstream, she added. Khamjani was taking a quick break during a rehearsal of a high-energy performance blending Bollywood moves and English country dancing with the unmistakable bounce of hip-hop moves.

“In an unexpected twist, Khamjani and her troupe were also dancing under a rainbow of swirling maypole ribbons – a sight more commonly associated with English village fetes rather than a basement in inner-city London. …

“For Khamjani, artistic director of Folk Dance Remixed, a collective putting a global spin on old-time English dances, a natural synergy exists. These are the dances of the people, bubbling up from the streets, pubs, village greens, dance halls and international communities that birthed them, Khamjani explained. An easy fit between age-old English country dances and house music exists, she pointed out. ‘It sounds weird but the steps are basically the same,’ she laughed. …

“Remixing maypole dancing is just one of the myriad ways that English folk culture is currently having a reboot, thanks to a new wave of switched-on folkies diversifying the scene. At the heart of this progressive movement is the Cecil Sharp House, a music venue and folk arts centre that’s home to the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS) and where Folk Dance Remixed perform regularly.

“Named after Cecil Sharp, a folk music enthusiast who roamed the countryside of England and the US South collecting folk music and dances in the early 20th Century, this temple to vernacular culture threw open its Arts and Crafts-style doors in 1930. …

“Over the last few years, the EFDSS has ramped up its outreach efforts to engage new audiences, mixing diverse cultural traditions to create new interpretations of ‘Englishness.’ Projects have included teaming up with musician Kuljit Bhamra, pioneer of the British Bhangra sound, an upbeat musical style that mixes traditional Punjabi beats with Western pop, to uncover similarities between 18th-Century traditional Kentish jigs and Bhangra music. There have been sea shanty lessons with rap verses taught to schoolchildren; and feminist-themed pop-up events, including a recording of the podcast Thank Folk for Feminism at the house.

“Certain projects have undeniably chimed easier than others. Take for example Queer Folk’s Queer Ceilidh parties hosted at Cecil Sharp House, where evenings of LGBTQ ceilidh dancing and drag acts have proved a sell-out success. …

“Joining me in the main hall at the Cecil Sharp House beneath a whimsical mural of folkloric creatures and abstract dancing figures, Katy Spicer, the chief executive and artistic director at EFDSS, pointed out that it is, however, a work in progress making the English folk scene truly inclusive. ‘In terms of diversity, ethnicity has been the hardest challenge’ she said. …

” ‘There was perhaps a tunnel vision back then and histories not recorded, which no one questioned until recently. We’re working to set the record straight,’ Spicer said, as a group of teenagers, part of the National Youth Folk Ensemble, shuffled onstage to tune violins ready for the evening’s show. ‘Particularly when you have English in your title, you have to address what it means to be English and whose England is it?’ …

“Exploring some of these overlooked histories and racial crosscurrents is Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne, a singer, musician and rising star of the folk scene, who in 2021 collaborated with the EFDSS on the Black Singers and Folk Ballads project. The work explored links between English folk and music-making among enslaved people in former British colonies in the US Southern states and the Caribbean.

” ‘I’d always been aware that there are songs and ballads that crop up across English folk music traditions and the music of Black America and the Caribbean, but perhaps hadn’t quite realised the extent of the shared repertoire,’ he told me. ‘These songs started life in Britain and migrated with the people to the Americas. It seemed that there was a certain amount of cultural exchange between the white colonizers and Black enslaved people,’ he said of his research, which unearthed examples of similar storytelling and melodies across the three traditions. ‘But the very nature of folk song means that as it’s passed along orally, you get an evolution.’

“Often still viewed as a relic from a dusty, bygone era, folk has also long struggled to attract a younger, hipper crowd. But things look set to change.”

More at the BBC, here. No firewall.