Photo: John Tlumacki/Globe Staff.

The Boston Globe reported recently on service workers marching “down Tremont Street to Boston Common, where they held a labor rally for new contracts and freedom to unionize.”

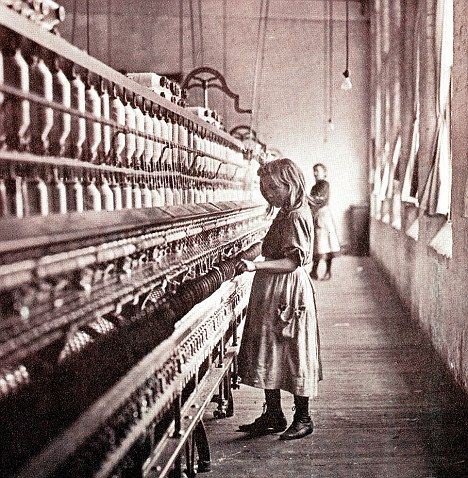

As a member of the general public, I don’t like being inconvenienced by a labor strike any more than the next person. But I know my history. I know what life was like when workers couldn’t strike and how some gave their lives to change the status quo. So I think of that on Labor Day.

At the Boston Globe, John Hilliard wrote recently about service workers, who are among the last to band together for better working conditions. We need to stay as grateful to them as we were during the pandemic.

“Hundreds of essential workers — including janitors, airport staff, and ride-hailing drivers — marched through Boston’s streets Saturday demanding better post-pandemic workplace conditions after laboring to keep the economy afloat during the health crisis.

“The Labor Day weekend demonstration, organized by Local 32BJ of the Service Employees International Union, drew together service workers from across Greater Boston who are members, as well as some who are organizing to join the union, according to Roxana Rivera, a labor organizer and assistant to 32BJ president Manny Pastreich.

“ ‘This is a moment for workers, because they put so much of themselves out there during the pandemic. They didn’t have a choice to work remotely. Service workers risked their own personal health, and those of their families,’ Rivera said. ‘The fact that they still struggle to make ends meet is unacceptable.’ …

“Luis Medina, of Malden, who works full time as a janitor, said he joined the demonstration because he is fighting to secure full-time hours for colleagues struggling to make ends meet with part-time employment. …

“Saturday’s demonstration came amid a dramatic resurgence in labor organizing and activity across the country — from Starbucks workers seeking to unionize to Hollywood writers and actors now on strike — demanding better pay, benefits, and working conditions from employers.

“Among the successes are Teamsters and UPS workers who have secured new contracts through union efforts.

Support for labor unions in the US has soared, with roughly two-thirds of Americans now saying they approve of them, according to a Gallup poll released Wednesday.

“And demonstrators in Boston Saturday, like Marty, a 43-year-old from Plymouth who works as an Uber driver and gave only his first name, drew a direct line between union successes nationwide and efforts to support workers locally.

“ ‘We are really important, because we are the people who move the economy,’ said Marty, who wore a Screen Actors Guild shirt to support striking actors. ‘If no one is making any money, no one’s spending anything, [and] that’s when the economy starts to suffer.’

“Rivera said that even though many people now can work from home, commercial buildings must still be cleaned and maintained, while airport employees and ride-hailing drivers remain vital to keeping the economy going. ‘We need to make sure that we are not leaving these workers behind,’ Rivera said. …

“Waitstaff and food service workers at restaurants along the route gathered at doors to watch the protesters. One worker left her restaurant, asked a union representative for a flyer being handed out and took it back inside.

“The city was packed with people enjoying a beautiful end-of-summer Saturday, and throngs watched from sidewalks, many taking photos with their phones. Several raised their arms in support, and one man on a scooter beeped his horn as he rode along Tremont Street.

“Elizabeth Hill-Karbowski, who was visiting Boston with family from Wisconsin, watched as demonstrators marched along Tremont Street and read from a flyer.

“ ‘It’s a timely type of demonstration for the Labor Day weekend, very peaceful, well organized and [it is] people just wanting to have their voices heard,’ Hill-Karbowski said. …

“State Senator Lydia Edwards, whose district includes East Boston, Revere, and Winthrop, spoke to workers in Spanish then English. …

“ ‘We celebrate all the victories that we have had, but also we need to remember the lives that we’ve lost in the fight for justice, and the lives that you have saved as workers’ during the pandemic, Edwards said.

“Ed Flynn, Boston City Council president, told the crowd: ‘When workers aren’t receiving a decent wage here in the most liberal, progressive city in the country, there’s something wrong with that.’ ”

More at the Globe, here.