Photo: Creative Commons.

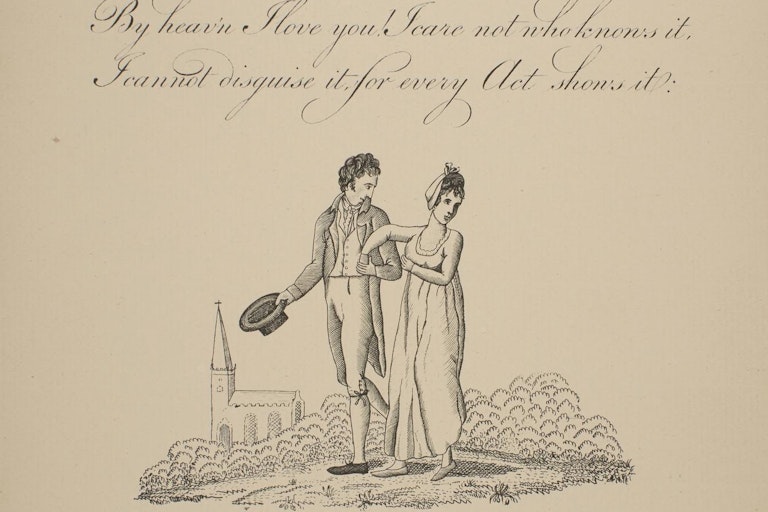

A popular Victorian-era Valentine Day’s card by Jonathan King,1860-1880, London Museum.

Do you make Valentines? It’s always been a favorite activity for me. I like cutting up different kinds of paper and I like having some kind of holiday on my horizon when the hyperactivity of the Christmas season is over. I’m the kind of person who, if her fruit cup arrives with a lacy doily underneath, saves it for valentines.

Today we look into research from Christopher Ferguson, associate professor of history at Auburn University in Alabama, to learn how Valentine cards were first manufactured in quantity.

Prof. Ferguson writes at the Conversation, “When we think of Valentine’s Day, chubby Cupids, hearts and roses generally come to mind, not industrial processes like mass production and the division of labor. Yet the latter were essential to the holiday’s history.

“As a historian researching material culture and emotions, I’m aware of the important role the exchange of manufactured greeting cards played in the 19th-century version of Valentine’s Day.

“At the beginning of that century, Britons produced most of their valentines by hand. By the 1850s, however, manufactured cards had replaced those previously made by individuals at home. By the 1860s, more than 1 million cards were in circulation in London alone.

“The British journalist and playwright Andrew Halliday was fascinated by these cards, especially one popular card that featured a lady and gentleman walking arm-in-arm up a pathway toward a church.

“Halliday recalled watching in fascination as ‘the windows of small booksellers and stationers’ filled with ‘highly colored’ valentines and contemplating ‘how and where’ they ‘originated.’

” ‘Who draws the pictures?’ he wondered. ‘Who writes the poetry?’ In 1864 he decided to find out.

“Today Halliday is most often remembered for his writing on London beggars in a groundbreaking 1864 social survey, ‘London Labour and the London Poor.’ However, throughout the 1860s he was a regular contributor to Charles Dickens’ popular journal All the Year Round, in which he entertained readers with essays addressing various facets of ordinary British daily existence, including family relations, travel, public services and popular entertainments.

“In one essay for that journal, ‘Cupid’s Manufactory‘ … Halliday led his readers on a guided tour of one of London’s foremost card manufacturers. Inside the premises of ‘Cupid and Co.,’ they followed a ‘valentine step by step’ from a ‘plain sheet of paper’ to ‘that neat white box in which it is packed, with others of its kind, to be sent out to the trade.’

“ ‘Cupid and Co.’ was most likely the firm of Joseph Mansell, a lace-paper and stationery company that manufactured large numbers of valentines between the 1840s and 1860s. …The processes Halliday described, however, were common to many British card manufacturers in the 1860s, and exemplified many industrial practices first introduced during the late 18th century, including the subdivision of tasks and the employment of women and child laborers.

“[Halliday] noted how the card with the lady and gentleman on the path to the church began as a simple stamped card, in black and white … priced at one penny.

“A portion of these cards, however, then went on to a room where a group of young women were arranged along a bench, each with a different color. … Using stencils, one painted the ‘pale brown’ pathway, then handed it to the woman next to her, who painted the ‘gentleman’s blue coat,’ who then handed it to the next, who painted the ‘salmon-colored church.’ …

“These colored cards, Halliday noted, would be sold for ‘sixpence to half-a-crown.’ A portion of these, however, were then sent on to another room, where another group of young women glued on feathers, lace-paper, bits of silk or velvet, or even gold leaf, creating even more ornate cards sometimes sold for 5 shillings and above.

“All told, Halliday witnessed ‘about sixty hands’ – mostly young women, but also ‘men and boys,’ who worked 10 hours a day in every season of the year, making cards for Valentine’s Day.”

Lots more at the Conversation, here. Do you usually recognize Valentine’s Day in some way? How?