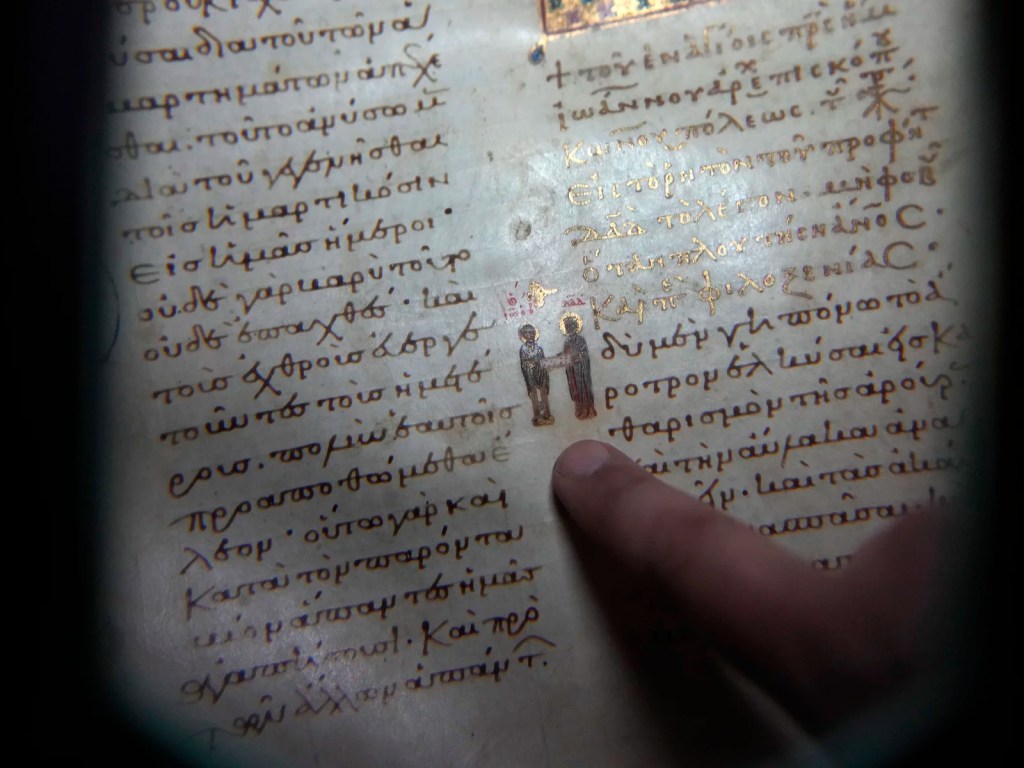

Photo: Museo Nacional del Prado, “El Greco. Santo Domingo el Antiguo.”

El Greco’s iconic altarpieces are reunited for the first time in nearly 200 years.

It’s impressive that museums not only preserve the wonders of the past but keep finding pieces of the past and reintroducing them. Consider how the Prado in Spain is currently uniting dispersed panels of El Greco’s first major commission.

Adam Schrader writes at Artnet that an exhibit at Spain’s Prado Museum “brings together the works the Greek painter Doménikos Theotokópoulos, better known as El Greco, completed for the Monastery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in his first major commission.

“The exhibit reunites works that El Greco, a master of the Spanish Renaissance, made for the church, and marks the first time they have been brought together since their dispersion, thanks to to the loan of the main altarpiece, ‘The Assumption,’ by the Art Institute of Chicago which has owned it since 1906.

“In ‘The Assumption,’ the Virgin Mary ascends to heaven on a crescent moon over Jesus’s open tomb while aided by a group of angels. It has a companion, made for the attic of the altarpiece, titled ‘The Trinity,’ that visually connects above it. …

“In the main altarpiece, ‘The Assumption’ is flanked by four other canvases which depict John the Baptist and St. Bernard on the left side and John the Evangelist and St. Benedict on the right side, which were meant to act as intermediaries between the earthly realm and the divine. Those works are housed at the monastery and in private collections.

“Other works El Greco made for the altarpieces include a depiction of the ‘Adoration of the Shepherds,’ a scene from the nativity; the ‘Resurrection’; and ‘The Holy Face,’ an iconographic depiction of [a legend] in which a woman obtained the ‘true image’ of Jesus from a cloth he had wiped his face on. …

“For the works that are housed at the monastery, a team from the Prado Museum had to convince the nuns to let them borrow the paintings.

” ‘It was difficult,’ Leticia Ruiz, the head of the Prado’s Spanish Renaissance painting collection, told the newspaper. She added that the monastery also lives off of its visitors and from the sale of ‘delicious marzipans’ that they make. So, the museum agreed to restore one of its pieces by the painter Eugenio Cajés in exchange for the loan.

“Funnily, the Prado Museum’s exhibit comes several years after France’s Louvre Museum tried, and failed, to borrow three works by El Greco from them. …

“El Greco was first documented in Spain in June 1577 and quickly received the commission for the new monastery, which was designed and jointly paid for by a powerful dean of the cathedral named Diego de Castilla and a Portuguese woman named Doña María de Silva. According to the museum, the two benefactors were buried at the monastery. The Greek artist was appointed to make the altarpieces at the suggestion of Diego’s son Luis de Castilla, who had met him in Rome a few years earlier. He completed it in 1579.

“ ‘The result could not have been more dazzling. He revealed himself as a perfectly developed artist, with a creative maturity that linked him to some of the best painters of the Italian Renaissance,’ the Prado Museum said on its website.

“ ‘El Greco. Santo Domingo el Antiguo‘ is on view at Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, through June 15, 2025.”

Some of El Greco’s works look strikingly modern, and I’m always suprised that they were painted in the 16th century — and especially that patrons back then could appreciate them.

Here’s more from Wikipedia: “El Greco was born in the Kingdom of Candia (modern Crete), which was at that time part of the Republic of Venice, Italy, and the center of Post-Byzantine art. He trained and became a master within that tradition before traveling at age 26 to Venice, as other Greek artists had done.

“In 1570, he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and executed a series of works. During his stay in Italy, El Greco enriched his style with elements of Mannerism and of the Venetian Renaissance taken from a number of great artists of the time, notably Tintoretto and Titian.

“In 1577, he moved to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death. In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best-known paintings, such as View of Toledo and Opening of the Fifth Seal. El Greco’s dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation by the 20th century.”

More at Artnet, here.