Photo: Brittany Schappach/Maine Forest Service.

The dreaded jumping worm.

“Jumping worms” sounds like a circus act, but they are unwelcome garden visitors that have become a menace for parts of the Northeast. I’d be interested to know if you have them where you live and what you can add to today’s report.

Catherine Schneider writes at Providence Eye, “Earthworms are generally seen as improving the structure and fertility of garden soil as they tunnel through the soil, consuming organic matter and leaving behind castings (worm manure) that are rich in nutrients, humus, and microorganisms.

“Unfortunately, there is a not-so-new worm in town that provides none of these benefits and can actually do great damage to soil structure and fertility: the so-called Jumping Worm. These worms devour the top layer of soil, leaving behind crumbly soil that dries out quickly, is prone to erosion, and makes poor habitat for many plants and soil dwelling organisms — including bacteria, fungi, and other invertebrates.

“The name jumping worms refers to several similar-looking species of invasives (Amynthas spp.) that originated in East Asia. … They have been in the US since the late 1800s, but pretty much remained underground until recently when their numbers and range have increased dramatically. The reasons for the recent rapid spread are not completely understood, although it may be due to climate change, as well as human activities which unwittingly spread the worms (e.g., gardening, landscaping, fishing, hiking). They are now found in more than half of US states, including many areas in Providence and Rhode Island.

“Unlike other earthworms that burrow deep into the soil, jumping worms tend to live in the top three to four inches of soil and in leaf litter and mulch. They are voracious eaters and can quickly deplete nutrients found in soil and organic matter. While other earthworms distribute their high nutrient-value castings throughout the soil, jumping worms excrete their castings on the soil surface, where the nutrients are unavailable to plants. The castings are fairly hard, and they frequently erode away in the rain.

“The combination of hard castings and aggressive churning of the soil results in a dry, crumbly soil structure, with large air pockets, which can impact the ability of plants to produce and anchor roots, absorb water, and extract nutrients. …

“Once jumping worms come to inhabit a garden, they rapidly increase in numbers, no mating required, as they reproduce asexually. Adult worms can have many offspring, and while the adults will die off after the first few hard frosts, the tiny egg cocoons they leave behind (which are virtually impossible to see with the naked eye) will survive the winter, emerging in the spring to start the destructive cycle again.

“Jumping worms can have a profoundly negative effect on forests and woodlands, as well as gardens and crop lands. A thick layer of leaf litter and organic matter (sometimes called the ‘duff’ layer) is essential to healthy forest soil. Native forest plants and trees have evolved to rely on this duff layer for the successful germination and growth of their seeds. After jumping worms have altered forest soil, native species may start to diminish while invasives move in and outcompete native species. This alteration of the forest floor and decline in forest health also harms wildlife that depend on native plants and trees, like ground nesting birds, amphibians and invertebrates.

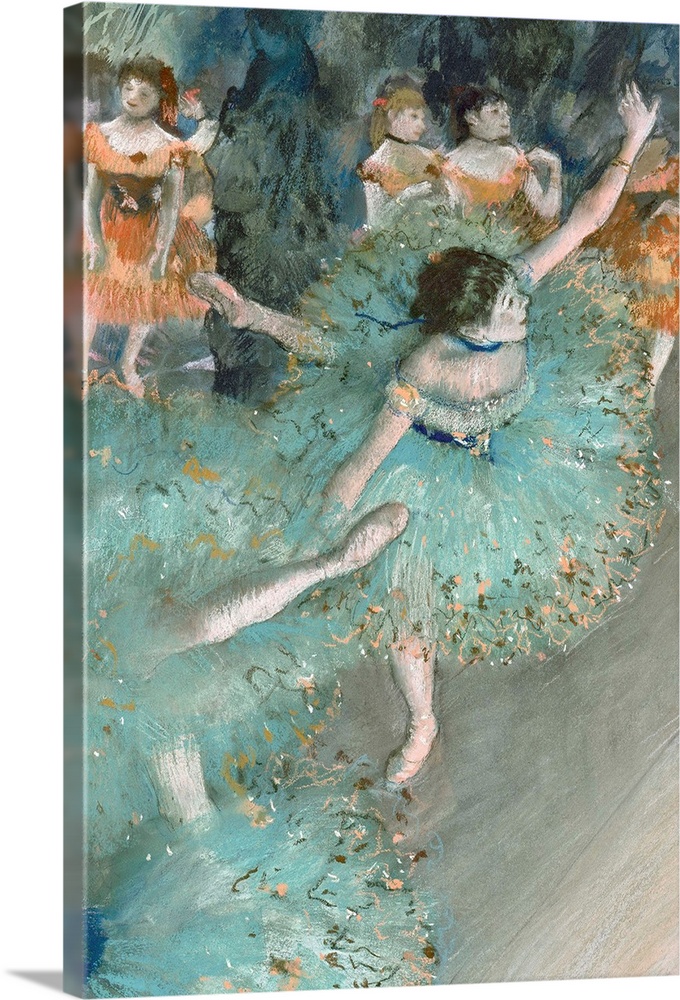

“Jumping worms are most easily identified by their behavior. They move across soil or pavement in a snake-like fashion and when you touch them or pick them up, these worms will thrash around wildly. This behavior has given rise to the names jumping worms, crazy worms and snake worms.

“Adult jumping worms can also be distinguished from other earth worms in Rhode Island by a milky white or pinkish band, called a clitellum, that fully encircles one end of their body (see photo above). … Jumping worms in Rhode Island do not attain adulthood until sometime in July or August. Before then, juvenile jumping worms, which lack the white clitellum, are difficult to identify. Young jumping worms can best be identified by their thrashing behavior when they are touched or handled. …

“If you suspect that you may have jumping worms, you can try this test: Mix 1/3 cup of dry mustard in a gallon of water and slowly pour this over your soil (it will not harm your plants). The mustard solution should drive any worms to the surface, where you can inspect and remove them if they appear to be jumping worms. …

“The main step in prevention is to take care with the plants, soil, compost and mulch that you bring on to your property. Purchase soil, compost and mulch from reputable dealers. If you are buying bulk compost or mulch, ask the dealer if the product has been heated to 131 degrees F for at least 15 days, which is the industry standard for killing weed seeds and pathogens and will certainly kill jumping worm cocoons which do not survive temperatures above 104°F.

“Cocoons can also be present in bagged soil, compost and mulch. To play it safe with bagged products, you may want to solarize them by placing the bags in the hot sun for three (3) days, with a piece of cardboard or other insulating material underneath them to prevent cooling from the ground below them. If you want to be extra careful, you can use a soil thermometer to ensure that the product has reached a temperature of 104 degrees F.

“When purchasing plants or accepting plants from friends, check for any signs of jumping worms. Starting from seed or buying bare root plants is safest. Alternatively, you can carefully wash off all of the soil around any new plants before planting in your garden.”

More advice at Providence Eye, here. No firewall.