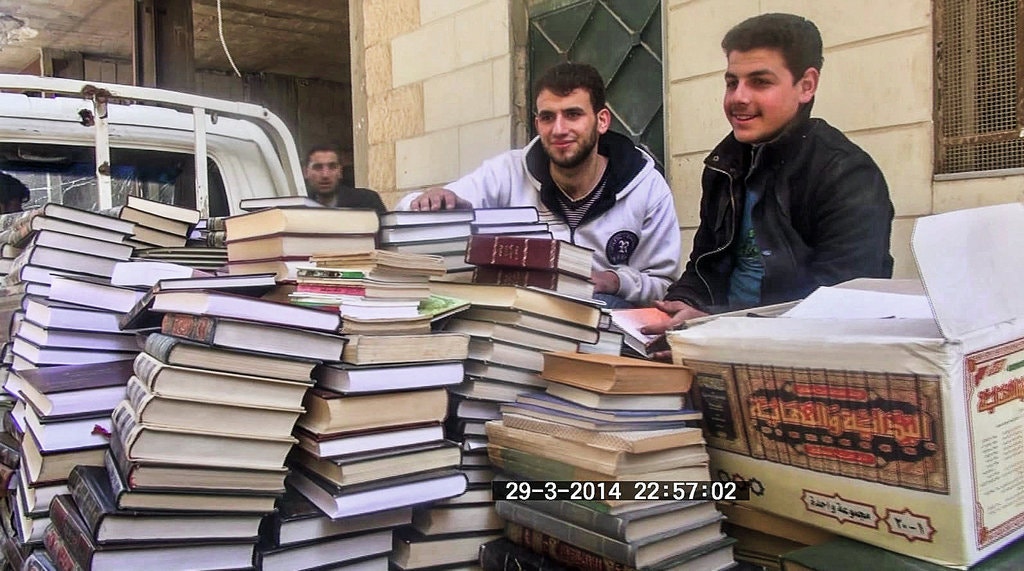

Photo: Taylor Luck.

“The Fardous Bookstore, once under restrictions imposed by the former Assad regime,” says Taylor Luck of the Christian Science Monitor, “now sells previously banned books to eager readers.”

Books are stronger than tyrants. We hold onto that thought. We know from both history and the belief of poets that the time of tyrants has an end. I think Shelley says it best.

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

“Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

“Nothing beside remains.”

If you don’t see the downfall of the pedestal in your own country at the moment, look toward Syria. Syrians have reason to believe that new tyrants won’t be replacing the hated Assad anytime soon.

After all, books are not being banned by the revolutionary government.

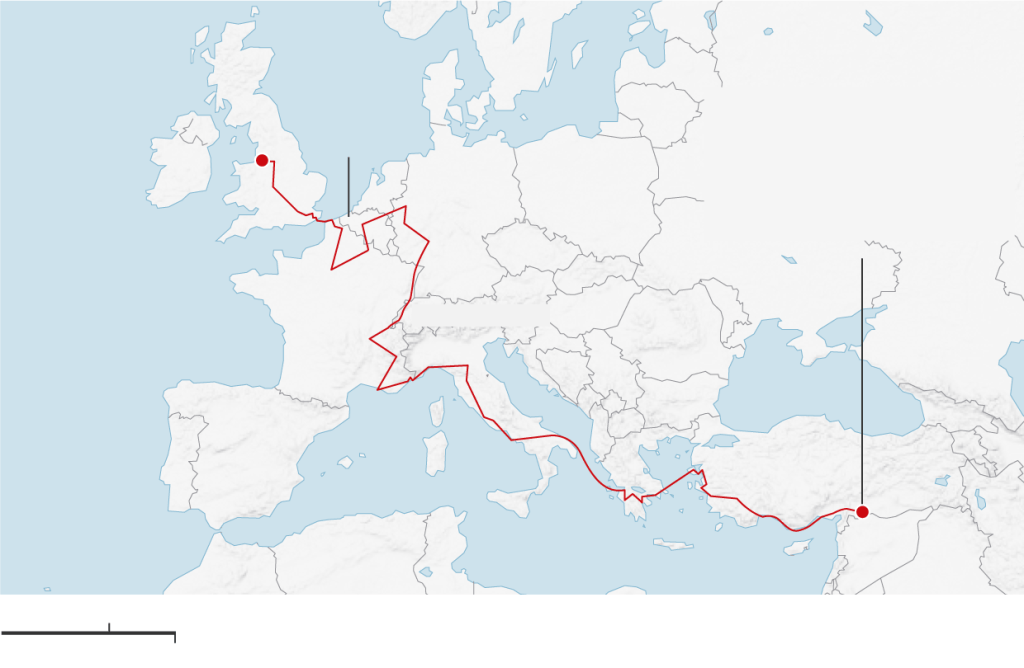

“Post-revolution Syria is becoming a page-turner’s paradise,” wrote Taylor Luck at the Christian Science Monitor recently.

“After years of being banned by the former regime, dozens of long sought-after books are flooding stores across Syria, literally spilling onto the streets. An epicenter of this new literary freedom is the so-called ‘bookshop alley’ in the Halbouni neighborhood of Damascus, a leafy street lined by two dozen bookshops and printers, big and small.

“It is here that Radwan Sharqawi runs the Fardous Bookstore, a small corner shop that his family has owned since 1920. The contrast between today’s Syria and the long period of Assad family rule is like night and day, he says.

“ ‘Before, we had daily interrogations by the security services,’ Mr. Sharqawi says. ‘Now everything is permitted, nothing is banned. Now is a golden era for books!’

For decades, any book written by an intellectual or an artist who had expressed opposition to the Assad regime – or who simply did not vocally toe the official line – was banned.

“So, too, were books that touched on Syrian history from any perspective other than the ruling Baath Party’s revisionist version. Titles on the history of the Israeli-Arab conflict, or anything on the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, were contraband.

“Islamic thinkers such as Ibn Taymiyya, the influential medieval Sunni jurist and scholar, were banned. So, too, were books by Brotherhood-aligned clerics. … Even a book as basic as a tafsīr, an annotated Quran with explanations and context, was banned, for fear it might contradict the Assad government’s tightly controlled Islamic authorities.

“ ‘These are texts about religion and God, not politics,’ says Abdulkader al-Sarooji, owner of the Ibn Al Qayem bookshop, as a customer browses shelves of leather-bound Islamic books, their titles engraved in decorative golden calligraphy. …

“As soon as the regime fell, Mr. Sarooji began importing books from Turkey and northern Syria to Damascus. Syrians are rushing to snatch up banned titles. …

“ ‘There is demand for banned books because people feel there is a gap in their knowledge, even in their religious knowledge,’ says Mr. Sarooji.

“The most dangerous texts during the Assad era – and the books in highest demand now – are works of literary fiction, titles that draw on the real experiences of Syrians who spent time in jail and suffered abuse at the hands of the regime. The most fiercely banned book was Bayt Khalti, by Ahmed al-Amri, which details the horrors faced by women in the notorious Sednaya prison.

“Now Bayt Khalti is prominently displayed on bookshelves and vendors’ roadside stands across Damascus – in both legitimate editions and blurry knockoffs that feed the high demand.

“ ‘This book was the most dangerous one,’ street-side book vendor Hussein Mohammed says as he waves a copy of Bayt Khalti. ‘If they caught you with this, you were a goner.’

“Another popular banned text, Al Qoqaa, or The Cochlea, details a Christian Syrian’s time in Mr. Assad’s prisons.

“Eyad, a young Damascene, purchased a book of fiction from Mr. Mohammed after spending an hour browsing in the bookshop alley. ‘There are a lot of books that I have wanted to read for years,’ he says.”

More at the Monitor, here.

Photo: Målerås

Photo: Målerås