Photo: Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff.

Lacey Kohler, Urban Greening Projects co-ordinator and Cristiane Caro, cofounder of Pearl Street Garden Collective, worked in the new microforest in Providence, Rhode Island.

I have posted a lot about Miyawaki urban forests in Massachusetts, thanks to my friend Jean (Biodiversity Builders), who showed me several she’s helped to create. I didn’t know that similar work was afoot in nearby Rhode Island.

These efforts are all about what a dense little forest can give to a city neighborhood where there’s very little nature left. It can remove dangerous carbon from the atmosphere while spreading biodiversity all around, making the city a healthier place for both humans and critters.

Ed Fitzpatrick reports on the Rhode Island venture at the Boston Globe, “The asphalt grid of South Providence is lined with multifamily homes and concrete sidewalks. But along Pearl Street, one lot stands out.

“It’s lush and green, with nearly 270 trees packed into a 1,000-square-foot lot. Officially called the Pearl Street Garden, it contains a tiny forest in the middle of the urban jungle.

“ ‘Microforests’ like this one are cropping up in places ranging from Elizabeth, N.J., to Cambridge, Mass., to Pakistan. South Providence has two, both along Pearl Street, created by Groundwork Rhode Island and the Pearl Street Garden Collective. …

“ ‘This isn’t habitat restoration on the scale that is needed in terms of the world,’ said Jacq Hall, director of special projects at Groundwork Rhode Island … but it is a really great way, especially in a city, for people to become very in close touch with biodiversity and why it’s important and why it’s also beautiful.’

“In May, more than 100 people came out to plant the microforest. …

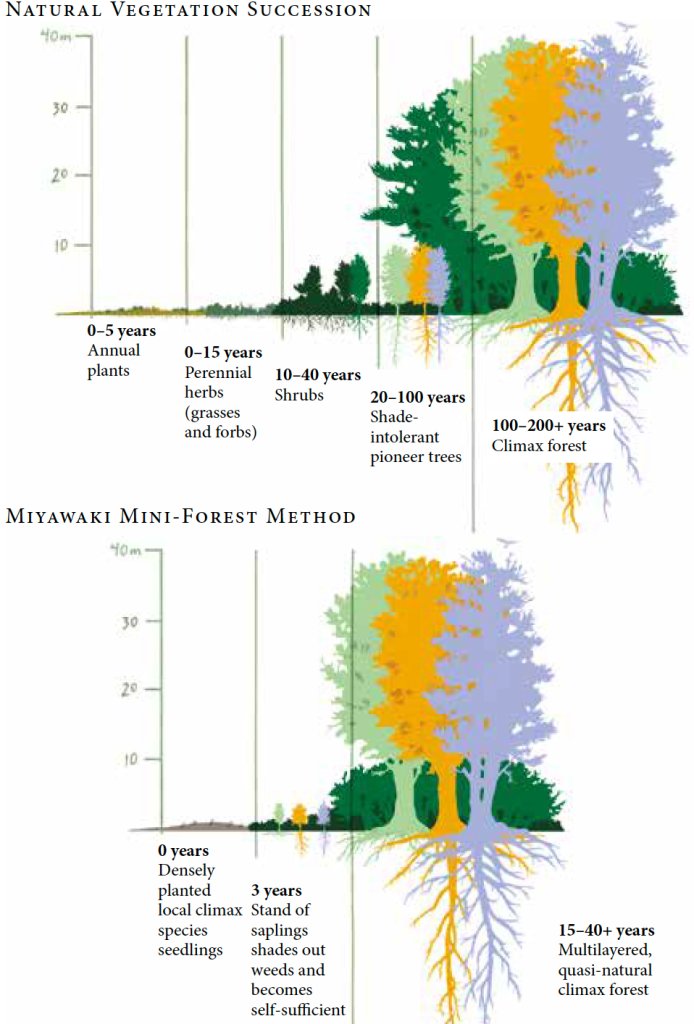

“The pocket forests adhere to the ‘Miyawaki method’ devised in the 1970s by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki, which calls for planting a wide variety of local trees in large numbers and in very tight quarters. …

“Massachusetts now has at least 20 microforests, according to Alexandra Ionescu, a Providence resident who is associate director of regenerative projects at Biodiversity for a Livable Climate, a Cambridge-based nonprofit that promotes ecosystem restoration to address climate change. …

“Rhode Island is the smallest and second most densely populated state in the nation, and a 2022 study found it contains 139 square miles of asphalt, concrete, and other hard surfaces, amounting to 13 percent of its land area. Hall said the benefits of forests and tree-lined streets are not distributed evenly in Rhode Island. …

“[Hall said], ‘We’re trying really hard to go back into those places that have been aggressively paved over and try to work in little bits of nature to bring those benefits to more people.’ …

“Hall said microforests help combat climate change because they grow so quickly. With plants packed close together, they both collaborate and compete for resources, racing to reach the sun first. She said research shows forests grown using the Miyawaki method grow 10 times faster than a traditional landscape planting. …

“Hall said projects such as this received a big boost in funding from the federal Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. ‘It was a historic moment,’ she said. …

“Groundwork Rhode Island and the Pearl Street Garden Collective are now looking for other funding sources” because of federal curbacks.

More at the Globe, here. And if you want to know more, search this site for “Miyawaki.” Or just click here.