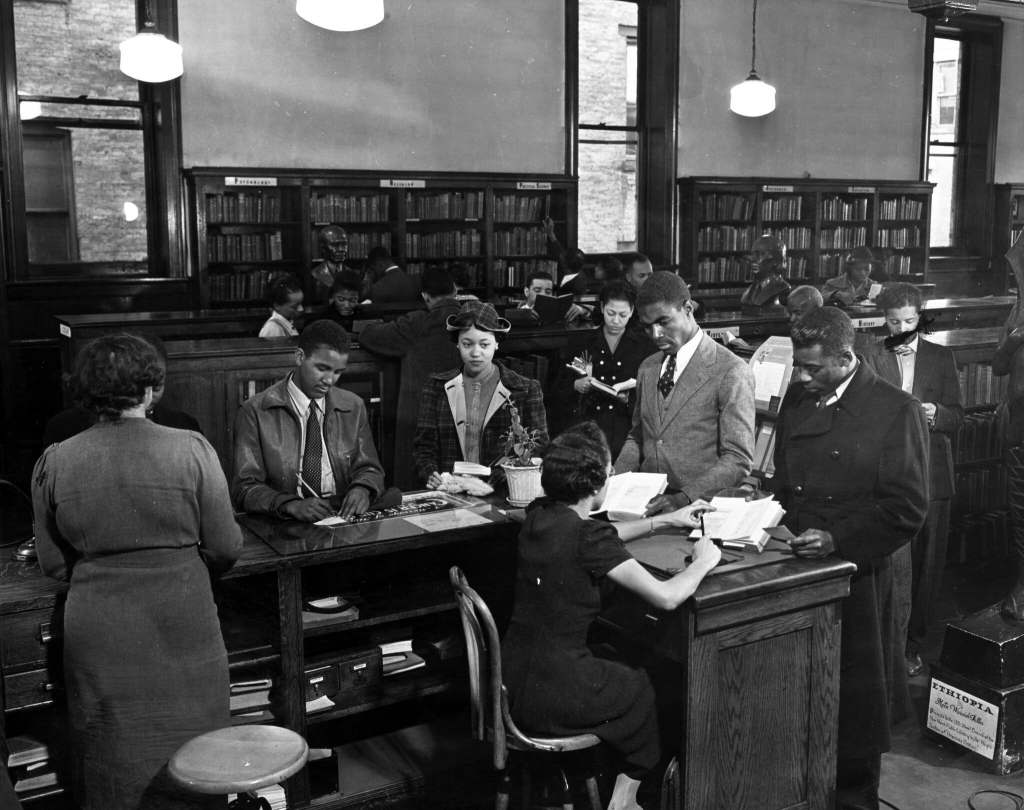

Photo: New York Public Library.

In 1925, the New York Public Library system established the first public collection dedicated to Black materials at its 135th Street branch in Harlem, now known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

I have read numerous accounts of what a public library has meant to poor children with insatiable curiosity. The most recent was the autobiography Up Home by future intellectual and university president Ruth J. Simmons. She grew up in a desperately poor Black sharecropper’s family in Texas. Books and encouragement from Black teachers meant everything.

Meanwhile in Harlem, Black librarians meant everything to generations of Northern children.

Jennifer Schuessler reports at the New York Times, “It was a banner day in the history of American libraries — and in Black history. On May 25, 1926, the New York Public Library announced that it had acquired the celebrated Afro-Latino bibliophile Arturo Schomburg’s collection of more than 4,000 books, manuscripts and other artifacts.

“A year earlier, the library had established the first public collection dedicated to Black materials, at its 135th Street branch in Harlem. Now, the branch would be home to a trove of rare items, from some of the earliest books by and about Black people to then-new works of the brewing Harlem Renaissance.

“Schomburg was the most famous of the Black bibliophiles who, starting in the late 19th century, had amassed impressive ‘parlor libraries’ in their homes. Such libraries became important gathering places for Black writers and thinkers at a time when newly created public libraries — which exploded in number in the decades after 1870 — were uninterested in Black materials, and often unwelcoming to Black patrons.

“Schomburg summed up his credo in a famous 1925 essay, writing, ‘The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.’ In a 1913 letter, he had put it less decorously: The items in his library were ‘powder with which to fight our enemies. …

“Today, figures like Schomburg and the historian and activist W.E.B. Du Bois (another collector and compiler of Black books) are hailed as the founders of the 20th-century Black intellectual tradition. But increasingly, scholars are also uncovering the important role of the women who often ran the libraries, where they built collections and — just as important — communities of readers.

“ ‘Mr. Schomburg’s collection is really the seed,’ said Joy Bivins, the current director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, as the 135th Street library, currently home to more than 11 million items, is now known. ‘But in many ways, it is these women who were the institution builders.’

“Many were among the first Black women to attend library school, where they learned the tools and the systems of the rapidly professionalizing field.

On the job, they learned these tools weren’t always suited to Black books and ideas, so they invented their own.

“At times, they battled overt and covert censorship. … But whether they worked in world-famous research collections or modest public branch libraries, these pioneers saw their role as not just about tending old books but also about making room for new people and new ideas.

“ ‘These librarians were very tuned in and understood that a cultural movement also needs a space,’ said Laura E. Helton, a historian at the University of Delaware and author of the recent book Scattered and Fugitive Things: How Black Collectors Created Archives and Remade History. …

“In the 1920 census, only 69 of the 15,297 Americans who listed their profession as librarian were Black. Many cities in the segregated South had no library services at all for Black citizens. And even in the North, those branches that did serve them often had few books geared to their interests, and sometimes no card catalogs or reference collections at all.

“That started to change, if slowly. In 1924, in Chicago, Vivian Harsh became the first Black librarian to lead a public library branch there. [But] no place captures the transformations of the era more than Harlem, where, starting in 1920, a white librarian named Ernestine Rose hired four young Black librarians at the 135th Street library. …

“The poet Arna Bontemps (who himself later became a librarian) recalled visiting the 135th Street library after his arrival in Harlem in 1924. ‘There were a couple of very nice-looking girls sitting at the desk, colored girls,’ he said. ‘I had never seen that before.’ …

“Other ‘girls’ at the branch fostered the neighborhood’s artistic ferment in different ways. Among them was Regina Andrews, a young librarian from Chicago (where she was mentored by Harsh) who came to New York City on vacation in 1922 and decided to stay. She … soon settled into an apartment at 580 St. Nicholas Avenue with two friends who worked at Opportunity, a new magazine that aimed to capture the creative ferment bubbling up in Harlem. Nicknamed Dream Haven, the apartment quickly became a salon and crash pad for some of the most celebrated figures of the period.

“It was there that Alain Locke held some planning meetings for the special issue of the Survey Graphic magazine that later grew into his landmark 1925 anthology The New Negro. And it was there that many Black artists and writers who attended the 1924 Civic Club dinner now recognized as an opening bell of the Harlem Renaissance gathered.”

Read more at the Times, here.

This piece gave me the shivers! Wonderful, wonderful

LikeLike

Libraries find a way. And do we ever need them! Book bans are said to affect Black students in particular.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These parlor libraries run by black activists, in their own apartments, are so fascinating. I will have to read more about them.

LikeLike

Valerie Boyd wrote an amazing biography of Zora Neale Hurston, which touched a bit on Harlem libraries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d love to see a movie about the Black Harlem librarians and writer meetings.

LikeLike

What a good idea!

LikeLiked by 1 person