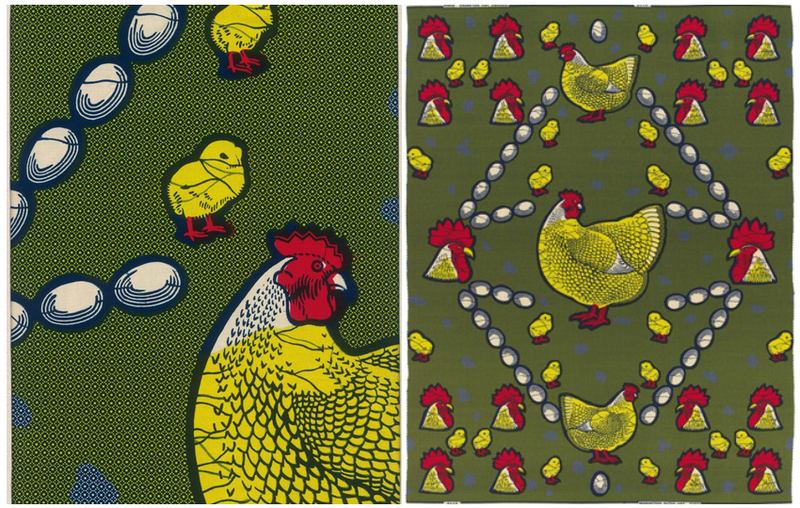

Photo: Amaal Said/JGPACA [June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive].

From a Mogadishu film week poster to VHS videos of pioneering art movies, June Givanni has collected a range of Black film artifacts and is now ready to share.

Sometimes people whose childhood struggles involve race-based discrimination grow up to embrace and trumpet the beauty of their heritage. I enjoy stories like that.

At the Guardian, Leila Latif interviews one such person, the founder of June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive.

Discussing her recent exhibition, “PerAnkh: The June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive,” Givanni played down the show’s title. Says Latif, “The Black British film curator, activist and archivist who created it is hesitant about positioning herself front and center.

“ ‘I don’t want it to sound like it’s all me, me, me,’ she worries. ‘My name is part of it because I worked as a curator for many years and collected work throughout the non-digital era, which developed into this archive.’

“Though she wants the films, documents, artworks and objects she has preserved to be the focus of people’s attention – from an installation of the earliest audiovisual works by the Black Audio Film Collective to new works by the Chimurenga collective from South Africa – Givanni is more than worthy of the spotlight. When she received the British independent film awards’ grand jury prize in 2021, the organizers said that she had ‘made an extraordinary, selfless and lifelong contribution to documenting a pivotal period of film history.’

Born in British Guiana 72 years ago, Givanni moved to the UK aged seven and was immediately underestimated.

“ ‘They put me with the five-year-olds because I was Black and I’d come from the Caribbean,’ she remembers. ‘My mum went to the school twice before they moved me up to my age range.’

“As an adult, Givanni collaborated with some of the most significant figures and institutions in pan-African cinema and across ‘different territories, different continents.’ She kept adding elements to her collection, she says, ‘because I needed to use them for subsequent programs and as part of building a body of knowledge and a whole series of resources that can be shared with others.’

“Lack of preservation has meant many of pan-African cinema’s masterworks have disappeared. In America alone, it is estimated more than 80% of Black films from the silent era are lost, and technological advances endanger film further. While physical film has a potential shelf life of hundreds of years, digital preservation requires constant migration to keep up with changing technology. …

“Givanni has faced changes in technology, politics and culture since she began in the early 80s. The first film festival she worked on was called Third Eye, inspired by the Latin American Third Cinema movement which set out to challenge Europe and North America’s dominance in film. For Givanni, the festival provided ‘an area to develop our own ideas about representation and taking charge. Pan-African cinema has always been a cinema of resistance. I can’t tell you how inspiring it was that there were all these people out there doing things that really chimed with what I thought should be happening.’ …

“She programmed festivals on five continents; worked for Greater London Council’s ethnic minorities unit and the Independent Television Commission; ran the BFI’s African Caribbean film unit and co-edited Black Film Bulletin, which relaunched in 2021 as a quarterly collaboration with Sight and Sound magazine, and has celebrated the under-sung work of film-makers. …

“The spirit of pan-Africanism was a guiding light, connecting all cultures that originated on the continent without treating them as a monolith. Givanni explains, ‘When I say pan-African, it’s not just the African continent; it’s the entire diaspora. All those significant histories are interconnected and cinema is very much part of that.’

“Choosing how to represent that history at Raven Row, with selections from an archive that now surpasses 10,000 items, was a gargantuan task. But Givanni immediately knew she wanted to include ‘a poster of the Mogadishu film week, given to me at my first attendance at the Fespaco film festival in 1985 by a Somali film-maker. Now people mention Somalia and they don’t picture these vibrant and strategic cultural events taking place there. …

“ ‘At the Havana film festival I bought a collection of silkscreen posters that will be exhibited. Lots of art can be seen digitally, but to see a silkscreen poster, the texture and the color of it – there’s an experience of culture and artifacts that goes beyond digital representation.’

“Beyond allowing the public to admire key objects from Givanni’s collection, the exhibition is structured around a program of films from the likes of Sarah Maldoror and Ousmane Sembène (the mother and father of African cinema). There is also an archive studio and reading room in the spirit of the exhibition’s title, PerAnkh – an Egyptian term for ‘a place of learning and memory.’ “

More at the Guardian, here. No firewall.