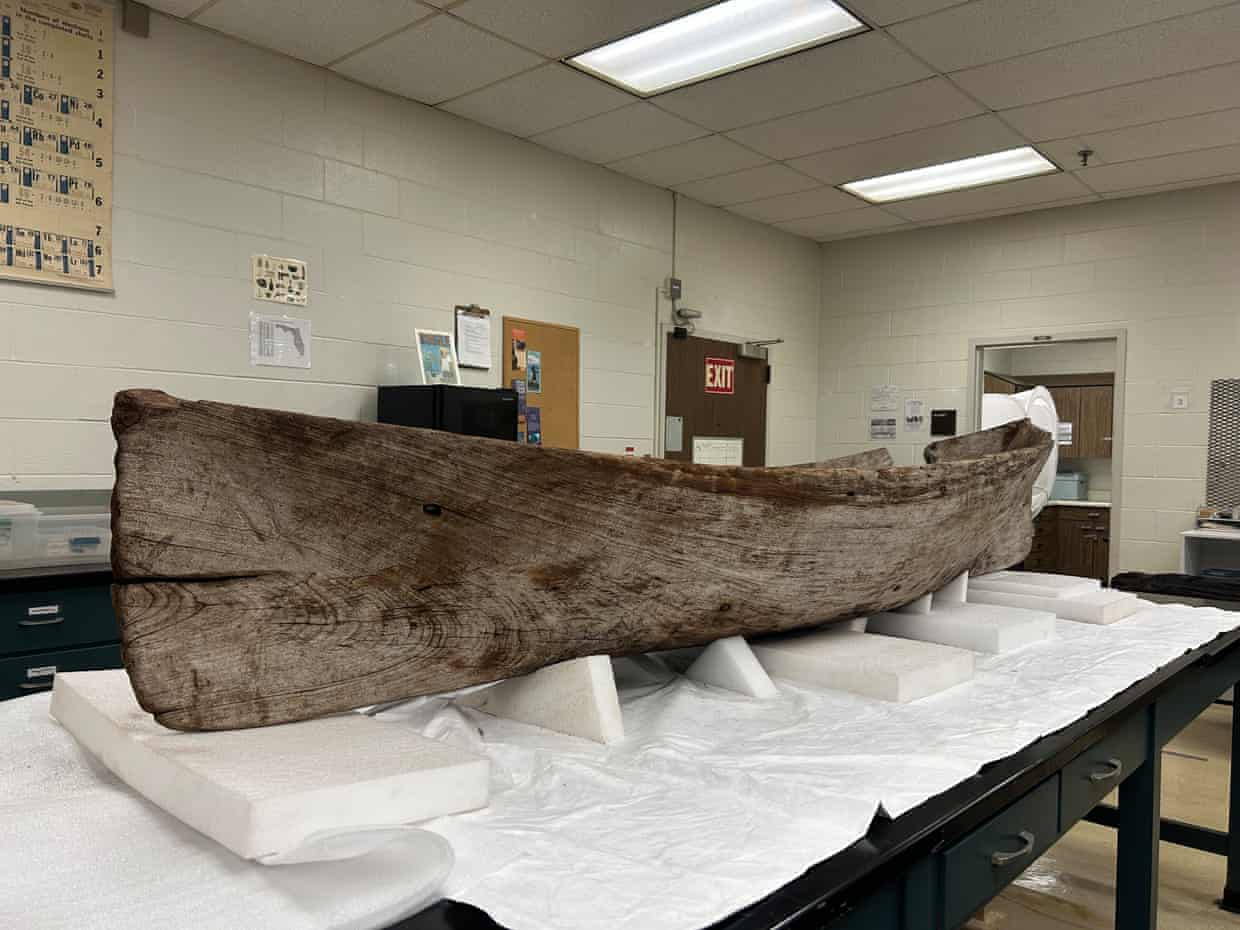

Photo: Florida Division of Historical Resources.

A 16th century canoe was discovered by a resident of Fort Myers, Florida, when Hurricane Ian made landfall in 2022.

When I was a kid on Fire Island, a big storm always meant there would be treasures on the sand the next day. We would hurry up the sidewalk to the ocean to see how the beach had reshaped itself and what flotsam and jetsam had washed up. Often the shore was littered with shells, jellyfish, or starfish.

Not that we wish for hurricanes, but extra big storms like that can uncover even larger surprises than starfish.

Richard Luscombe notes at the Guardian, “Florida already claims to be the world capital of golf, shark bites and lightning strikes. Now a remarkable discovery following a devastating hurricane has enhanced its position as a global leader in another distinctive field: ancient canoes – some even prehistoric.

“State archeologists have just completed a painstaking preservation of an ancient wooden canoe discovered by a resident of Fort Myers during the cleanup from Hurricane Ian in 2022.

“It joins 450 other log boats or canoes dating back thousands of years recorded or preserved by the Florida division of historical resources. But this one is unusual, officials say, because it is the first they have seen made of mahogany, and probably the first to originate outside Florida, possibly in the Caribbean.

“The age of the fragile 9ft canoe is under analysis through carbon dating and other scientific processes. Investigators are pursuing a theory that it might be a dugout cayuco crafted by Spanish invaders who settled in the region during the 16th century.

“ ‘We compared it to canoes that we have in our collection and previously recorded, and it’s a very unusual form, so that was the first hint it was not necessarily from Florida,’ said Sam Wilford, Florida’s deputy state archeologist. ‘On the surface there’s tool marks made by iron tools, and we know that that is a historical date because that’s when the Europeans introduced iron tools into the Americas.’ …

“ ‘The tree may have died much earlier than when the canoe was constructed from it. It might have been driftwood, or stored somehow before it was made as a canoe.’

“Hurricane Ian caused ‘catastrophic’ damage when it slammed into south-west Florida in September 2022 with 150mph winds and a storm surge of 18ft. The canoe is believed to have been pulled from a riverbed and ended up in the yard of a Fort Myers resident, who discovered it as he cleaned up after the storm and alerted state officials.

“ ‘It had been clearly submerged in water; there’s lots of stain marks on it, [but] it was dry when we received it,’ Wilford said, adding that it was then lightly vacuumed and cleaned with soft brushes, and that each stage of its careful conservation was photographed.

“Florida has had more discoveries of old canoes than any other place in the western hemisphere, and more than 200 separate sites have been recorded, officials said. Many of the canoes were made and used by Native American tribes, including the Miccosukee and Seminole tribes, who inhabited large swathes of the state, particularly the wetlands of the Florida Everglades.

“The oldest, Wilford said, is a canoe discovered near Orlando, estimated to come from the middle Archaic period up to 7,000 years ago.

With about one-fifth of Florida covered by water, the prolific use of canoes by its residents throughout history is unsurprising.

“ ‘It’s because of the environment,’ Wilford said. ‘Native Americans and then later on Europeans needed canoes to get around, and then the wet environment also led to preservation.’

“Canoes collected in the state’s historical resources division are stored in what Wilford said was a central archeological collections facility that is not open to the public. But the department operates an artifact loan program, with 26 canoes currently on display at museums across the US.

“ ‘It’s incredibly exciting,’ Wilford said. ‘Every canoe, and every fragment of a canoe, tells a story, and each one is unique.’ ”

More at the Guardian, here. (Although the Guardian has no paywall, I just upped my random donations to an actual subscription as independent journalism seems especially important in these trying times. Even tiny donations are welcome there.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/cf/99cfb75f-f2a3-48fa-86e5-8b3e405e04e1/head_of_the_male_figurine_with_tattoos_or_scarification_width_55mm_figure_by_j_przedwojewska.png)